A Mouse in the Walls of the Lesser Redoubt (Part 8)

by

Nigel Atkinson

To A Mouse in the Walls of the Lesser Redoubt (Part 7)

Denholm hesitated at the threshold of the Shine. The boundary was strewn with bloated corpses and the stink from them was hideous, but that was not why he wavered. Nor did the certainty of death hold him back.

He was afraid of being judged. By every normal criterion his life had been a failure; as Master Monstruwacan he held the greatest responsibility — to keep his people safe until he died and the burden passed to his successor. His attempt to shake his people out of their million-years-long lethargy had failed — or had succeeded disastrously, he couldn’t decide which. The pain of his survival was like an iron band around his heart. He had failed as a father too — his belief that he could raise a child while carrying the office of Lord of the Redoubt revealed as unbelievable arrogance.

He had failed humanity in the round and the singular. Now he was afraid that the Fixed Giants would judge him a failure too. Steeling himself, he prepared to step into the Place of Gas. He would die, but maybe in his last moments answers would be revealed to him.

Before he could step forward he was engulfed in a blizzard of bees. They battered his body, forcing him to his knees, and then fell back to form a writhing wall. A solitary bee flew close to his face and he realised that it wasn’t an insect at all, but a tiny nugget of metal held in the air by spinning, iridescent wings. He looked closely as the machine tore itself apart and the fragments burst into dust and mist. Like a visual fugue, the dissolution spread through the entire swarm leaving Denholm surrounded by a slowly twisting tornado of microscopic entities. He felt something beat on his mind, then slide away before it could be grasped.

“I can’t hear you,” he shouted. “I can’t hear the Master-Word.”

The maelstrom paused then flowed away from him. It fell like mist on the ground then rose to form a tapered column of smoke that coalesced into the form of a slim youth. Denholm had never met Bergthora Baumgard’s son, but he recognised him. Caliban was changed, however, and, as Denholm turned his head, splinters of blue light from the Shine fell through the boy’s body. When he spoke it was as though Denholm’s mind was suddenly encased in ice and shards of glass were being dashed against it.

Y o u h a v e l o s t t h e m a s t e r w o r d

“Please, your voice is strange — it grates.”

The boy-thing considered his options for a moment and, when he spoke again it was not the Master-Word, or the Night Hearing. Denholm had no idea how the Jackotrade avatar was communicating with him. This was something new.

You must not enter the Death Lands. Your work is not done.

“I have to know.”

There is nothing to know. You have never been in the Shine, either in mind or body. You have never had discourse with the Fixed Giants. You are too small for them to notice.

“But—”

The boy’s skin turned into a quicksilver mirror that reflected Denholm’s life from the perspective of the multi-billion-generation history of the Jackotrade tribes. They told his life story backwards, starting with the destruction of the Redoubt, an event made all the more cataclysmic by their hidden machinations — hundreds of billions of the machines giving up their tiny lives fuel the explosion with surface-bonded hydrogen and oxygen.

Shaking with barely contained anger, Denholm raged. “I only wanted to shake them out of their complacency. I couldn’t understand why the explosion was so large. Why did you make it so bad? Why kill so many? Why destroy the Redoubt?”

The boy-thing ignored him, then revealed Naani’s successful attempt with the Master-Word machine, and how the legions of Jackotrades gave her the strength to contact her Bright Warrior from the Great Redoubt.

Denholm felt crushed, and overwhelmed with guilt. “I didn’t know. I thought she failed — is she alive?”

Your child is abroad in the Night Land. Soon you must leave this place and go to her. There is a force we cannot influence that will hunt her. You must save her.

“Where is she?” Denholm shouted.

Your life has been a lie.

The words were like a slap, and Denholm flinched because he knew what they were going to say next.

The Kernel was a lie.

They showed how they manipulated his mind, just as they had done with the thirty-seven thousand six hundred and fifteen Masters before him. Memory blocks fell and he remembered hammering on the Kernel’s walls, desperate to escape as it filled with seething legions of Jackotrades. Tides of them washed through his skin and flowed into every space in his body, gifting him profound peace and clarity. He was like a blank white canvas, on which they painted their abstractions of reality. Their revelations rung with truth — in his heart he always doubted he had the strength to stand with the Fixed Giants — what human did?

They were merciless, showing how they had manipulated him, and his people, at every turn, and how they were the true agents of change in his little Kingdom. Humanity was, as he had long suspected, a tiny mote caught in the swirling morass of life forces that covered the Earth. It was an epic vision: ants and bees, humans and the beasts of the Night, moss growing on frost-blackened rocks, the things in the Shine, Jackotrades and all the other myriad tribes of this troubled world — each individual a mote of life sharing a minuscule portion of the World Soul.

Gripped by an urgent need to take stock, Denholm stood up and carefully brushed the dirt from his gown. In his heart, he suspected there were lies here.

“Who am I talking to?” Suddenly animated, Denholm paced up-and-down in front of the boy-thing, waving his arms extravagantly and speaking in volleys of words. “The son of Bergthora Baumgard, a trillion Jackotrades, or some unholy amalgam of child and machine?” Denholm drummed his fingers theatrically on his chin. “How to tell? What questions would reveal your true nature? I know, why don’t you tell me something — anything — which would prove that the boy is the puppet of the machines, or that he wears them like a cloak, or that a chimera stands before me.”

The Caliban-thing remained silent.

“You offer no proof, so I will assume, for the moment, that you are lying. Let us consider an alternative hypothesis, one that was old in this world long before the hands of men crafted your earliest ancestors. Its first tenet can be stated simply — we are fallen spirits chained by irrationality and doubt to an existence far beneath our true place in the universe.”

Perhaps that is where you deserve to be.

“We can change. Three million years ago there was a man called Harlequin who taught that our spiritual destiny lies in our own hands, and is influenced only by our characters and deeds.”

What happened to Harlequin?

“A question with a snare at its heart. Sadly, I am unable to avoid stepping into it. He was killed aeons ago, and I had the last of his followers executed twenty years ago.”

All of them?

The Master smiled, but refused to answer. “Why is my daughter so important?”

Why do you think she is?

Denholm laughed again. “You don’t know, do you?” He gestured at the Caliban-thing. “This metal and flesh concoction was your last hope, wasn’t it? I don’t care how many billions of generations of you there have been, in the end you had to find a way to speak directly to us. Your schemes and eternal wars are beyond human ken, but you can’t understand us either, and wedding yourself to this pathetic excuse for a human didn’t help, did it?”

No.

The word rang with truth, and Denholm sensed an undercurrent of boiling anger. He knew it wasn’t from the Jackotrades — human emotions were foreign to them — this hatred was pouring from the boy. As the torrent of bile grew, Denholm felt sorrow. Caliban had a black heart all of his own, and he must have initiated the symbiosis with Jackotrades, but Denholm was appalled at the tortures he had suffered. But the child-monster was still dangerous, and would become a raging beast when the Jackotrades left him. He shook his head as if clearing away mental cobwebs. Then he started to laugh — just a chuckle at first, but quickly turned into uproarious, gut-clutching laughter.

We do not understand.

It took Denholm several attempts before he could speak. When he did, he was still barely able to keep his bubbling hilarity in check.

“Of course you don’t,” he said between sobs of laughter. “Twelve million years ago, a hundred philosophers laboured for a hundred years to define Godhead, and the best they could come up with was God was a standing wave in the unified consciousness of humanity.”

We do not understand.

“No you don’t. You know, we really should have had this conversation before.”

We do —

“I want to tell you my credo: I chose to believe in the transcendental nature of all life. I chose to believe that humanity has greatness woven in its genes, as have all other living things — including the machine tribes infesting this tragic child before me. Above all, I chose to believe that our destiny is in our hands and, if I die today, it will be in the knowledge that I have lived my life by this set of beliefs. You — the Fixed Giants — the Silent Ones — the old lady who lives in a bucket on the shore of the Waveless Sea — it doesn’t matter whom I met in the Kernel. Do you seriously think I would have done the things I did if I hadn’t believed in them?”

The Caliban-thing didn’t reply. Denholm couldn’t be sure but he thought that the fluctuations in its mirror-surface were slowing, or maybe becoming more regular in their nutations.

“I have known all my life that the Lesser Redoubt was doomed. Our population has collapsed to unviable levels over the last three million years. There are maybe fifty thousand of us left, out of the half million who launched the great endeavour eight million years ago — five hundred thousand brave souls defying the Night, determined to recover the world for its true inhabitants. At least we tried!”

You failed.

“Did we, or is this just more lies?”

Your conceptions of truth and lies are redundant.

“No they aren’t, at least not from my perspective — and that’s the only one that matters.”

A limited viewpoint.

“Where is my daughter?” Denholm demanded.

The Jackotrades abandoned Caliban, flowing from every organelle and every cell, collecting in the tiny spaces of his body, and then pooling in his veins and arteries, entrails and lungs. He spasmed, vomiting a silver stream of machine life. His skin turned silver, and then dead white as his symbiotes deserted him. A glistening argent pool formed at his feet, then disappeared into the black earth. For a long time he didn’t dare breathe, so terrified was he that the merest motion would cause his body to slump into a bindless sludge. Finally, a single choking breath told him he was alive, and a cautious step proved that he was still vital. He wrapped his arms around his chest and held his hatred close. The Master’s footprints were easy to follow.

The snake women’s attacks went on until the last of the boys was dead. As Rauli slumped over, his face purpled and his tongue bulging and bloodied, his attacker decomposed into a slinking oily ash. For half-a-day, the boys had been singled out one-by-one for attack. The first had happened with blinding suddenness. A fist of viper-tailed women, with eyes like burning embers and serrated hooks instead of hands, had burst from behind a rock and surrounded Paamis. While the others held his friends at bay, one of them embraced him in a quickly tightening embrace, and crushed the life out of him. When her work was done, the snake woman unwound her deadly grip and fell into torpor. Her sisters slunk away, leaving the fast-putrefying killer behind. The children stuck close together as they climbed the long slope up from the dry seabed and, when the next attack came, they were better prepared. In the end it made little difference; the snake-women were cunning and single-minded. When they fixed on a victim — always a boy — it was only a question of time before one of them broke through and killed him.

With Nyven dead, the attacks ended. Only Naani and three of the girls — Jessamy, Winter and Tigris Tinsley — were alive of the sixteen children whom the Moramor had led into the Night Land. The others hugged each other and wailed, but Naani stood apart, her head held high. The Earth was silent, apart from a keening from the northwest.

Jessamy looked up from her grief. “What’s that noise?”

“Just the Night Land,” Naani said. “Don’t upset yourself.”

The other girl flinched and buried her face in her hands. Naani ignored her. She had no comforting words for them, they would either have to pull themselves together, or they would die soon.

Just like my father’s people.

So far as she could tell, she alone had shared the last moments of the Redoubt’s defenders. At first she had thought their deaths were waking nightmares, but as dozens, then as hundreds of them, had fled their lives, she could no longer deny the scale of the tragedy she was witnessing. The end had happened so quickly; it took a handful of minutes while she stood lookout and her friends wept for the lost boys.

“You don’t care!” Tigris Tinsley shouted.

Naani listened to the Night Land. She could hear things scurrying among the rocks, things emboldened by the death of the last Lamia. Her awareness encompassed every creature for miles around — from slithering worms to creeping beast-men — all of them keen to feast on four lonely girls. There was another voice: in the distance, her Bright Warrior was striding quickly towards her. She sent a wordless cry of love into the Night. She could not grasp his reply, but she was sure that he had heard and would quicken his pace.

There were two other voices that did not belong in the Night Land. She recognised one of them — and it filled her with a sad joy. The other was clouded and shifted like sand in a gale wind, like it was part of the world, yet apart from it. Instinct told her who it was, and that she would have to deal with it soon.

“Come,” she said to the others. “My father is in the wilderness with us. He is a good distance away and needs our help — we must hurry.”

Caliban had closed to within a hundred paces of his enemy, so close that he could smell him, even if he couldn’t sense his thoughts. When the Jackotrades drained from him, they took their world-sense with them. Suddenly, the man looked in his direction. Caliban threw himself flat into a low ditch filled with swarming mites. The lice skittered away from him. He slapped his palm, down killing a thousand of them, then held up his gore-splattered hand and looked at it for a long time. It wasn’t the same, he realised; killing things wasn’t as satisfying when you couldn’t feel their tiny souls snuffing out.

Wiping his hand on a rock, he found some consolation in the hope that killing his enemy might reawaken a little of his old passion. Repeating that happy thought over and over, he stood up cautiously — and was slammed to the ground by a mass of claws and fur. At first Caliban was furious that he had allowed a beast to sneak up on him. Then he was fighting for his life. The beast-man knocked the wind from him. Through his breathless agony, Caliban saw the creature prepare to leap again and, just as it fell, he rolled aside and staggered to his feet. For an instant his attacker seemed baffled by the escape of its prey and Caliban took the opportunity to leap on its back. He grabbed two fistfuls of the mat of greasy hair on its head and smashed its face against the rocky ground. Before the beast-man could recover, Caliban wrapped his arms around its neck and squeezed as hard as he could.

It was several minutes before Caliban heard the beast-man’s death rattle. He shoved his face close to its head and listened in vain for its life force taking wing. He kicked the dead creature away and squatted on his haunches, listening closely for other potential attackers. He was about to restart his pursuit, when another idea occurred to him. Laughing at his cleverness, he found a sharp flint flake in the rubble, and began to skin the beast-man. When he was done he threw the mattered pelt over his shoulders like a cloak.

Unsurprisingly, his enemy was gone from sight. He was about to start tracking him when he realised that he was thirsty. There was no water anywhere near, but he squeezed the beast-man’s pelt, forcing a few drops of blood and fat into his upraised palm. He swallowed the bitter, salty slop. It was awful, but it would give him the strength he needed for his last task.

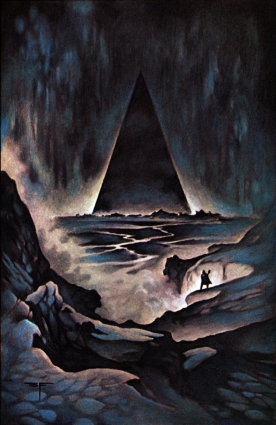

Naani and her father met on small flat-topped hill. It was capped with a large triangular rock a hundred yards along each side. Neither of them knew that it was the base of one of the prehistoric watchtowers of their people. Unused since the Redoubt was completed, all traces of humanity had long ago been scoured from its face. The underside was covered with eight million-year-old writings, but they were lost to all but the trillions of Jackotrades who had been drawn to this climatic moment — and they did not care about them.

Father and daughter approached each other slowly. The other three girls cowered beside a nearby boulder and watched in disbelief. Naani held her hands out and Denholm softly took them in his. They did not say anything but, for the first time in their lives, looked into each other’s eyes. Their mutual understanding had been long coming, but was complete, and all sins and omissions were set aside in a profound act of reconciliation. Naani rested her head on her father’s chest and listened to his slow steady heartbeat. The universe was arrested in her perfect moment — the blowing dust stopped in mid-air — the ice-cracked rock flake defined gravity — the cellular processes of the lowliest algae paused in reverence.

Beneath her feet, the Jackotrade tribes waited.

Then something rushed in a blur of stinking hair and pale limbs across the flat rock, screaming and wielding a flint knife. Denholm pushed his daughter aside and stepped into Caliban’s path. He slammed into the creature, shattering its bones and tearing its sinews. They crashed to the rocky ground. After a moment, Denholm heaved Caliban aside — Naani rushed up, grabbed a fist-sized rock and finished the boy-monster off. She threw her weapon away, and knelt by her father. His hands covered the flint knife that was buried in his chest. She pressed her head to his body and listened as his heart stopped beating.

I love you.

I know.

It was an hour before Naani let go of her father. The other girls stood around in silence, unsure of what to do or say. Then she stood up and looked towards the Southwest. She could hear her Bright Warrior from the Great Redoubt. He was many days away yet, but she knew with absolute certainty that their meeting would not be too long delayed.

“I am going to the West,” she said without turning to look at her companions. “My salvation and my love is hurrying North, and I long to join him. You can come with me if you wish. The way will likely be hard, but that is true of all roads in this desolate land and it is time for us to stop being afraid of the dark.” She paused and waited for the other to reply. When they didn’t, she shook her head sadly, and continued. “First, through, we must bury my father. I cannot stomach the thought of leaving him naked in this place.”

“You should look at this, Naani,” Jessamy said in a near-whisper.

Naani looked back at her father’s body. It was lying in a smooth shallow depression in the rock. As she watched, the grave slowly deepened and trickles of fine dust started to cover the body.

It took the Jackotrades six hours to bury Denholm, and when they were done his resting-place was covered with an oval slab of smooth, impenetrable granite. Naani offered silent thanks then; after kissing the monument, she set out to meet her destiny.

The End

© 2002 by Nigel Atkinson.

Image copyright by Stephen Fabian.