A Mouse in the Walls of the Lesser Redoubt (Part 7)

by

Nigel Atkinson

To A Mouse in the Walls of the Lesser Redoubt (Part 6)

“Has he spoken yet?” the Gallowglass asked.

The Perfect shook his head as he unlocked the cell door. “Not a word, My Lord. He eats when we feed him and uses the midden hole when he needs to. The rest of the time he stares at the same spot on the wall. Even when he sleeps, his eyes are turned to the North-West.”

“Very well, you are dismissed. You should go to the Buttery, I hear they’ve found a barrel of almost unspoiled biscuits.”

“But, My Lord—”

“I will remain here until you return. Go, get some food inside you while you can.”

The Gallowglass closed the cell door and sat down beside the Master. He hardly recognised him. Skin hung from the man’s bones like a translucent shroud, and his eyes were lifeless and lorn. He reached inside his jerkin and pulled out a leather pouch. He took a sticky lozenge out and pressed it into the Master’s hand.

“Here, My Lord, a peppermint comfit, I recall you liked them.”

The Master looked blankly at the lozenge, and then swallowed it without chewing. The Gallowglass was content to sit with his old friend for a while. The four weeks since the disaster had passed like a single exhausting day, each hour indistinguishable from the last.

In the early days, attempts had been made to search for survivors in the in the underground parts of the Redoubt — with some success — a couple of thousand people were rounded up. They were put to work helping search for food and other survivors. The Master was found wandering in the rubble surrounding the Great Arbour, but he didn’t seem to know who he was.

Everyone near the old research centre, the Arbour and the Earth Current generator died in the first few minutes. Circles of destruction spread from these loci, burning or crushing all in their path. Sixteen Guild Houses were destroyed, including those of the Bee Masters, Mathematicians, Hour Criers, and Silk Masters. The already fire-damaged Shambles had been swept away. Annihilation roared up the shaft to the pyramid, and spread to the fringes of the Underground Country and beyond. It was impossible to know how many had died. Countless tunnels, bridges and caverns had collapsed, slicing the lost home of Mankind into isolated, doomed islands. The metal pyramid was least damaged and, despite the catastrophic decompression caused when the airlocks failed, took the fewest casualties. Chill air rushed through cracks in its ancient metal walls, bringing life to the surviving Prefects. Half the order — five hundred men — was lost, either killed outright or missing in the underground regions. The Moramor and the Master’s chosen children were among the lost.

Eventually, the people of the Redoubt found a new spirit amid the ruins. Leaders came to the fore, among them a middle-aged woman called Essa, who set aside her grief over her husband and daughter to lead and inspire her people.

This was as well — the Prefecture had other problems.

It took several days for the creatures of the Night to realise that the pyramid was vulnerable. Even when the three great lights flickered out they hesitated. Eventually, the bravest, or most stupid, chanced the limits of the old defences. Claws scratched tentatively at glassy rock, long hairy noses sniffed cautiously. For the first time in eight million years, electric death wasn’t waiting for them. Howling gleefully, they charged towards the pyramid. For two days they attacked the metal walls. Well-built and, until recently, well maintained by the Jackotrades, the task was beyond them. High above, grim-faced Prefects waited and sharpened their weapons. It was almost a relief when the first squirming thing began to crawl towards the open gantries at the apex. For a time the battle was easy; the Prefects waited until the monsters were close enough, then swept them to their deaths with raining metal fragments or burning oil. But the guard was only a handful against inexhaustible legions. The geometry of the pyramid helped — the attackers had to bunch closer as they neared the apex — but at times it seemed like the whole structure was covered in writhing horrors. Twenty Prefects fought shoulder to shoulder for thirty minutes, until the next shift replaced them on the killing floor. Human chains filled the long stairways, ferrying rubble and twisted metal — anything that could be hurled down on the attackers — to the thin line of fighters.

The Gallowglass was in the Master Monstruwacan’s Audience Chamber watching the bodies of the fallen being wrapped in their bitumen-soaked cloaks. They were laid on a mound of kindling made from broken furniture. When the worst happened, the penultimate act of the living would be to save their dead from the beasts.

A young Prefect approached him. Barely past his teens, the lad looked beyond the point of exhaustion. His armour was cracked and his Diskos scored with blue streaking. A gaggle of dishevelled Monstruwacans trailed behind him.

“My Lord, the Monstruwacans wish audience with you,” the Prefect said.

“What do you want, Master Lanyard?” the Gallowglass asked.

Lanyard was quite young for a Monstruwacan, barely out of his seventies, and normally looked almost bright-eyed compared to his fellows. The Gallowglass doubted that he had ever seen a more defeated bunch.

Lanyard gestured at his colleagues. “We have news. For a week, the surviving Lords of the Empathy have listened for traces of the Night Speech, and called out to the survivors trapped below.”

“Did you find anyone?”

“Precious few whom we did not already know about.”

“If nothing has changed, why bother me?”

“Because something has changed,” a particularly wizened Monstruwacan said. His voice was like sandpaper on softwood. “Two things are new. A clarion voice is calling out the Master-Word, someone is coming, a great hero—”

“With an army?” the young Prefect asked too quickly. He looked at his feet, blushing.

“Ah no, he is on his own,” old Monstruwacan said. “He is a lone hero, sallying out from the Great Redoubt, his mind on noble deeds. He seems to be preoccupied with searching for his long-lost love. He is obviously quite mad. Wandering in the Night Land will do that to a body.”

The aged Monstruwacan’s words trailed off into muttering.

“You mentioned two new things,” the Gallowglass said.

“I did? Of course I did.” His voice fell to a barely audible whisper. “Bitter things are spawning in the Shine. When they are birthed they will make the creatures that assail us now seem like fluttering moths. Their desires are plain, they want the Master Monstruwacan.”

“I will not permit that,” the Gallowglass said.

The oily river wound slowly through a complex waterscape of ox-bow lakes and little islands. The Moramor and the children had been travelling for a week, hoping to find some way back to the Lesser Redoubt.

Four weeks ago, they were settling down inside the hidden castle when an unknown, but obviously tremendous disaster rocked the Redoubt. They were safe inside the castle’s twenty-foot thick walls, but when they opened the door a week later they were met with desolation. The tunnel they had escaped through was crushed. Another tunnel ran away from the castle, but the Moramor was reluctant to risk it, fearing it led into the Night Land. After twenty days with no sign of rescue, he handed the decision over to the children; and they voted to try the dangerous road. After several false starts, and much backtracking, they found the river. The Moramor was immediately suspicious of such an easy path but, in truth, it was the only way open to them.

“Where do you think we are?” Arian asked. They were sat together at the front of the boat, dipping their paddles in the water only when the boat drifted away from the middle of the stream.

“It is difficult to say. The river seems to be following a slow North-Western curve, but with so many twists and turns and false leads I have no idea how far we have travelled. I suspect that we have passed beyond Redoubt Hill and are somewhere near the great cliffs bordering the old sea, but that is only a guess.”

Arian smiled at him, her eyes twinkling in the soft phosphorescent light falling from the algae-encrusted walls. “You guesses are worth ten other men’s certainties.”

There was a quickly stifled giggle from behind, and shushing whispers. It was no secret that Arian had offered to share her sleeping bag with him — and that he had refused.

Suddenly, there was a shout from ahead. “An opening — an opening ahead.”

The Moramor checked that his Diskos was at hand. “Paddle steadily,” he ordered. “I must see where we are.”

Torches were lit, but when they crossed the threshold into the Night Land, their feeble light was swallowed by the immense darkness. They paddled in silence, drawing their boats close together. The river wound along a deep-cut valley with steep, unclimbable walls. As their eyes adjusted they realised that the darkness was not complete. The sky was dull red, its dark light reflecting in the world around them. For a long time there was nothing to see. Then the landscape began to slowly change. The valley became broader and shallower, and they found that they could look a little way into the Night Land.

A pillar of fire rose to the West, and beyond it lay the cold burning blue of the Shine. The Northern horizon was lit by a dull red glow, and to the South there was a range of black hills. But most of them were looking to the East — towards the Lesser Redoubt. Many miles away, it was only visible as a faint distant glow. The Moramor took a telescope out of his pack and scrutinised the distant light for a couple of minutes, and then handed the instrument to Arian. It took her a moment to focus the telescope, and then the pyramid sprang into view. It was lit with strands of small lights and glowed red at the apex. Gradually, she realised that the strands of light were moving slowly, randomly, and the hill below was covered in a black writing mass.

“They are under siege from the forces of darkness,” the Moramor whispered. “The end cannot be far away.”

Then someone in another boat started screaming.

“Here they come again lads — steady — let them get on the parapet — steady — wait for the command — now!”

At the Gallowglass’ command, a dozen ten-foot long steel pikes drove outwards skewering the wave of attackers. He put his back to one of the pikes, helping it to pivot in its socket hole, lifting the writhing, screaming thing impaled on it above the defender’s heads. He didn’t look too closely at the creature as the pike fell back, sending the dying beast crashing among its fellows. The glimpse he had of it was enough; it had a ring of hands around its neck, and each hand had an eye in its palm.

“Reset the pikes,” he shouted as he rushed forward, slashing as the head of a beast-man poked above the parapet. The creature ducked under his roundhouse swing then leapt towards him. He smashed an armoured elbow into its face, then took its head off with a backhand swipe of his sword. Strong hands pulled him back as the pikes crashed forward again. The world turned into a vortex of claws and teeth and tentacles and parts that defined naming. The Gallowglass slashed blindly with his sword and screamed the order to retreat. Somehow he made it inside, then ran to join the line of men forming against the back wall. He was handed a Diskos. He hefted it, running his hands over the incomprehensibly ancient symbols cut into its shining disk.

“Form a skirmish line!” he shouted. “Spread out and give your mates plenty of killing room!”

Tensely the line of men waited. Outside on the parapet, brave men were fighting and dying. They tightened their grip on their weapons and waited their turn.

The riverbank was covered with tens of thousands of crabs. Their carapaces shone blood red. The largest were as wide as man’s outstretched arms and the smallest no bigger than a fingernail. The tiny ones swarmed incessantly over their larger brethren. Claws were raised, and clacked continuously.

But the worst thing was their eyes — little white balls on red stalks that followed every move in the boats. As the party drifted slowly past the growing congregation, thousands of stalked eyes watched. The Moramor turned his head, and it seemed to him that every crab was watching him and him alone. He knew this was an illusion. The knowledge did not help ease his dread. Dully, he remembered his duty.

“Close your eyes,” he whispered to Arian.

“I can’t.”

He tried to close his own eyes, but the crabs wouldn’t let him.

“Look behind us!”

A hundred yards behind them a man was running through the crabs. At least it, seemed to be a man, it was hard to tell with hundreds of tiny crabs writhing over his body. He screamed in silent agony and waved his arms beseechingly.

“Headcount!” the Moramor shouted. “Is anyone missing?”

“All here — all here — all here—”

The man stopped, spread his arms wide, and disintegrated in a welter of scarlet gouts. In the gloom it was impossible to tell whether he had been a false man made from crabs, or a real man ripped into tiny gobbets by them.

“Steady there,” the Moramor said in a whisper that carried along the line of boats. “They’re only beasts, and we’ll soon be past them.”

With his men nearing their utter limits, the beasts regrouped. In the temporary lull, the last Gallowglass called his Sergeants together and told them his last secret and let them decide how to act. They agreed that the end was near, and their support for his decision was unanimous. The Gallowglass took six men to the hidden room under the Master Monstruwacan’s Audience chamber. Monstruwacans Lanyard and Argus were waiting for them, and together the nine unlocked the seals and turned the valves.

Mechanisms stilled since the time of the Builders came to life. Eight million years ago, the Builders conceived a defiant, optimistic gesture to commemorate the day when humanity finally retook the Earth. That day never came, and the secret design was forgotten by all but the long line of Master Monstruwacans and Gallowglasses.

Slowly at first, but with quickly increasing speed, mercury began to spill from reservoirs hidden throughout the pyramid. It flowed into narrow pipes twisted into tori around metal cores. Dynamos spun and capacitors filled with electricity, ready to feed power to cables buried in the outer skin of the pyramid. The mercury continued its journey, eventually falling into catchpots cut in the rock surrounding the central shaft. The mercury counterweight removed; huge carefully balanced levers toppled — and the pyramid began to flower.

A shudder passed vibrated the metal walls as the levers fell. High above, warring men and monsters were flung about like rag dolls. A few creatures held on for a few seconds, but when the walls began to open, most slipped and fell, setting off an avalanche of flesh.

An arrow-straight vertical crack appeared in the metal wall of the pyramid, and began steadily widening. The metal was vibrating, and the slab was moving inexorably sideways and outwards. Capacitors discharged, and the surface of the pyramid was bathed in pure white light.

Hundreds of the creatures of the Night lay dead or dying at the foot of Redoubt Hill. Thousands more were transfixed, unable to comprehend what they were seeing. Some tried to run away from the bright-lit flower blooming on the hill, but the press of bodies behind them made escape impossible. In the panic hundreds more died under stamping hooves and slashing claws.

After an unending hour the Moramor's group left the crabs behind them, and paddled on for half a day without incident. Suddenly the river began to quicken. Within a few oar strokes they were battling to avoid being swept away by a raging cataract. Crashing waves threatened to capsize their boats, and water poured dangerously over the gunwales. Progress was impossible, so the Moramor ordered them to turn to the riverside. His boat reached the shore first, and after helping beach it, he plunged hip-deep into the river to guide the other boats. His strong arms, and a fair measure of luck, allowed all three boats to reach safety.

The Moramor sat down, shucked his boots off and poured a quart of oily water out of each. “We should climb yonder hill before we go on,” he said. “We must find as much as can about the lay of the land before we chose a path.”

They climbed to the top a small cinder hill. The Lesser Redoubt was about ten miles to the North. At first they through it was on fire, but their telescopes revealed something wondrous — the Redoubt had blossomed — its three sides had opened like petals spilling clean light into the Night. The attacking horde had been pushed back and were holding their distance a mile from the base of Redoubt Hill. The refugees cheered when they saw that the beasts had retreated, but the Moramor kept his own council.

“My father is alive,” Naani said quietly. “But he is in pain. He blames himself for the disaster. I wish I could go to him but I can’t.” She turned to the South and pointed. “Someone is coming. I have to go and meet him.”

“Who is coming, Lady Naani?” the Moramor asked.

“Don’t call me that,” Naani said, and turned her face away from him.

“We should stay together,” Arian said. “We are safer if we stay together. The Moramor can only be in one place at once, and we need his strong arm is we are to survive in this place.”

The Moramor embraced her. “Ah, sweet healer,” he said softly. “Our paths must part soon.”

She pushed him back. “You intend to return to the Redoubt?”

“My brothers will be making their final stand soon, and I must join them.”

Arian waved at the horde surrounding the Redoubt. “Are you mad? You can’t get though the enemy’s lines! They would cut you down in an instant.”

“Maybe. But I still have some tricks to share with the beasts of the Night. The land to the North-East is thinly populated. I think I can get through.”

“You would leave us? You would leave me?”

The Moramor hefted his Diskos. “I am sorry,” he said. “I love you — I love you all — but that isn’t enough.” Then he turned on his heels and raced down the hill at a dead run. Distraught at his betrayal, the children watched him for ten minutes until he disappeared in the gloomy, boulder-strewn land.

Arian angrily dismissed Naani’s efforts to comfort her, walked a little way off and squatted down on her haunches with her head bowed. The others respected her grief, and let her be while they discussed what to do next. Talk quickly turned to Naani’s vision. She opened her mind and told them all she knew about her dream warrior and Mirdath, the love that had lasted aeons, and the urgent sense of destiny she felt. Her friends were sceptical, but in the absence of a better plan, they agreed to follow her South.

They loaded one of the boats with supplies and dragged it like a sled down the scree slope to the seabed. They passed the huge waterfall that they nearly had been swept over. The water fell in an iridescent stream that glistened with a thousand oily colours. But when it touched the bone-dry sand at the bottom, it disappeared, shedding not a single drop, or moistening a grain of sand. The place had an air of unrequited want, and they quickly set off South.

The seabed was featureless and soon swallowed them, leaving their long wake of dust as the only mark on the endless gloomy landscape. The going was easy and, after a time, Naani felt she was almost flying over the surface. She knew it would be harder when it was her turn to help with the hauling, but for the moment she was enjoying the exercise. An illusion began to grow in her mind — she was standing still, while the Earth rolled under her feet. She fancied this was how the people of the moving cities must have felt.

“Hello!” someone shouted.

Naani blinked and looked around. Her friends were gone, and the only feature she could see was the arrow-straight line of dust she had raised, and that disappeared in the murk a hundred yards away.

“Hello!”

“I’m over here!” she shouted.

Aldous and another boy — Rauli — ran along her dust trail. They held a short rope between them.

“Don’t worry, we’ll get you back to the rest,” Rauli said.

“But how—” Naani began.

“People are wandering away,“ Aldous said. “We didn’t notice at first. It’s like we’re all in a trance.”

Walking quickly, it took five minutes to reach place where Naani had gone astray, then another ten minutes to reach the caravan. Along the path, other dust trails led away into the darkness. Two other rescue parties joined them. Three people had walked away — and only Naani had been found — the other trails ended for no clear reason and with no one in sight. They waited a little while, but it was obvious there was no hope. Ropes were dug out of storage, and everyone tied themselves to lines fanning out from the boats. The going became harder.

Caliban knew everything and was everywhere. He flowed like a shimmering wave through the soft sedimentary rocks, and touched every facet of the World Soul. He was as big as a mountain and as tiny as the smallest part of a living cell. He knew all the secrets of the Fixed Giants, and he understood the immemorial machinations of the Jackotrades. He itched in sympathy as sweat ran down the back of the man from the Great Redoubt while he battled yet another beast on his road to meet his love. The endless chattering of the Silent Ones amused him, and he would have laughed — had he lungs and a mouth — at the real reason why the Silent Watchers watched. The world’s glorious pointlessness both moved him deeply and amused him. His life was like an endless moment — past, past present and future piled higgledy-piggledy together — life, birth and death indistinguishable.

He had no idea much time had passed since the mobs he briefly inspired with his old destructive passion turned on their would-be saviour. He didn’t care. At the climactic moment of his life, the Jackotrades had protected him.

He was special.

He recalled with glee the astonishment on the faces of his attackers when he fell into the stone floor. His body spread like smoke through the rock, but he could still sense their baffled anger. Seething resentment at their treachery rose in him, and he longed to unleash his new mastery of the elements on them. But the Jackotrades took charge and forced him to migrate away from the central parts of the Redoubt. Despite his helplessness, the sensation was wonderful, and was it was a long time before it dawned on him that that the extraordinary process was quite painless — unlike the coruscating agonies his previous merging with solid objects had provoked. As his vision widened to encompass the whole world, he could not bring himself to hate it for the unnecessary agonies that it had inflicted on him over the years.

It was only when the Jackotrades told him that they had one last task for him, after which he would be free, that he started to hate again.

The Great Door was a hundred feet tall and wide. Cut from a twenty-foot thick slab of pink-veined granite, it was opened once every ten thousand years. Floods of electric fire would scour the hill on which the pyramid stood, sweeping the beasts of the night away. Then in a strange gesture of defiance, a flock of a few hundred butterflies would be released. The reasons for this strange ritual were long forgotten, but obscurity was never enough reason to stop doing something in the Lesser Redoubt.

The door was open, and it would never be closed again.

Three hundred Prefects lined up in four perfect ranks just inside the Great Door. A group of six hundred or so ordinary men and women stood behind them. They had made the difficult climb up from the underground lands. The Gallowglass looked on them with immense admiration; they had no weapons but they were ready for the final battle. Many carried musical instruments — drums and flutes, harps and bells — the rest bore bright flowers or skilfully wrought handicrafts. Among the ordinary people stood a small number of former Monstruwacans, including Lanyard and Argus. They had cast aside their trappings of office, and wore the rough-cut garments of working people.

Behind them the remaining Monstruwacans fretted in their rich gowns, peered over the heads of the Prefects and citizens, and looked fearfully into the Night Land. Suddenly, a man wearing a dirty grey robe pushed through the ranks of the Monstruwacans. “Who is in charge here?” he asked.

The Gallowglass turned, then knelt before the Lord of the Redoubt.

“There is no need to kneel before me, Lord Gallowglass. I have no rank anymore. I am just a man, nothing more or less. Call me Denholm, like you did all those yours ago when you were the sternest of my tutors.”

The Gallowglass smiled broadly. “It is a long time since anyone called was permitted to call you that, old friend. It is Law that the Master cannot have a name — do you bring revolution with you?”

“I fear revolution is upon us already,” Denholm said quietly. He touched the Gallowglass’ battered armour. “I see you have been in battle, old friend.”

“The Redoubt has been hard pressed lately . . . Denholm. I don’t understand what is stopping them now.”

Denholm waved his hand, taking in the Prefects, the loyal Monstruwacans, and ordinary people of the Redoubt. “The Word is being flung across the Land by the defiance of people of the Redoubt. The Word is terrible to them. It denies their place in our world — even those who were once human—”

“Blasphemer!”

“Keep that rabble quiet, Sergeant,” the Gallowglass ordered. Six Prefects lined up in front of the cowering Monstruwacans, who fell into a resentful silence.

“The Word is in their flesh and minds. Starkly, it shows them how alien they are. How they have lost their own true place more surely than humanity has — at least we had a chance, if only a small one, of reclaiming our world — their home is gone forever. For tens of millions of years they have been denied even the small solace of glimpsing the greater universe from which they came. You see, our ancestors' great gamble paid off, albeit too late to keep the hordes of Night out—”

“My Lord, I have no knowledge of the things you speak of,” the Gallowglass said.

“I know. Don’t worry, I speak for posterity. We may all die this day, but there are things out there than are all-knowing and all-remembering. Now, where was I? Ah yes, the gamble — we had a moon once you know? We destroyed it to try and keep the dark at bay. We failed to do that, but we succeeded in sundering two of Creation's great rivers of consciousness from their homes. Mankind was driven from the surface into dead cities of metal, while the Invaders were denied the universe that is their true domain. Little wonder we that we never found common ground.”

“A joke?”

“The biggest joke in history, Lord Gallowglass.”

“What now then?”

He smiled and kissed the Gallowglass on the cheek. “Now I must go. I have matters to attend in the Night. Be true, old friend.”

Denholm walked slowly through the Great Door and into the Night Land. The beasts made no attempt to attack him and, when he reached their front rank, it parted to let him through. Then they closed ranks and swallowed him up. The Gallowglass’ eyes filled with tears, and he could hear weeping among the ordinary people. He hung his head in shame that he had allowed this thing to come to pass.

“It is not your fault, my friend,” someone said in a familiar voice.

Disbelieving, the Gallowglass turned to greet the Moramor. His old friend stood beside him, smiling.

“You have seen battle today,” the Gallowglass said.

The Moramor ran a finger over the gash that split his face from forehead to jaw, and then turned to look at the Prefects and the people behind them. His voice fell to a whisper. “And we will see it again soon — what a terrible waste.”

Naani wanted to run away, and never stop running, but she couldn’t leave Nyven and Aldous to die alone. They had been marching for several hours when the two boys walked into a patch of quicksand. Although frightening, the danger did not seem too great — after all, they were all roped together — rescue seemed easy. But this was no ordinary quicksand. The boys had been pulled down to their knees by the time their friends were organised. There still seemed to be plenty of time. The rescuers leant on their ropes. For a moment everything went well, and the boys began to ease out of the morass.

Then they started screaming. Their would-be rescuers dropped their ropes and stared in horror at the petrifaction climbing up the boy’s legs. Before their eyes, their friends were being changed into pillars of sandstone. At first, the change was rapid, and quickly reached their chests. Then it slowed down, taking six hours to climb to their necks. Three hours had passed since they stopped screaming or breathing for all it mattered, but somehow they still clung to a semblance of life. In their extremity, the boys had grown strong in the Master-Word, and their agony beat in waves across the world. Naani opened her heart and mind to the hurricane of agony.

In the end she was so soul-whipped she didn’t notice her friends die.

Someone helped her stand up and whispered comforting nonsense to her — something about not being able to continue South, about having to retrace their steps, then maybe turn to the West. Naani nodded automatically, she had no real idea what Arian was talking about, but leaving this terrible place seemed a good idea. As they turned their boat around, Naani took one last look back. Aldous and Nyven were gone, replaced by two amorphous humps of gritty yellow rock.

“Prefects avaunt!”

Three hundred Diskoi burst into whirling, fire-spitting life and the front rank gave voice to a thundering cheer.

“Life!”

The cheer mounted as the other ranks joined in.

“Life! Life! Life!”

Behind them the ordinary people of the land raised their own glorious cacophony, filling the air with music and petals.

The Gallowglass and Moramor took their place side-by-side in the Vanguard. They kissed then the Gallowglass raised his Diskos high in the air.

“Shall we walk to meet the enemy?” he asked his men.

“No!”

They were trotting as they passed through the Great Door. They accelerated down Redoubt Hill and, by the time they hit the plain below were running pell-mell. The ground was broken but that made no difference — they raced over it as if on winged feet. The legions of the Night backed away, trampling and gouging each other in their haste to escape the charge. But the army of Night was vast and, the great horde behind prevented escape. Diskos whirling, the Prefect’s first rank hit full on like a thunderstorm touching earth, and tore a hundred-and-fifty-yard-wide gap into the enemy horde. The next two ranks hit the flanks with almost as much venom and the fourth tore into the breach.

For ten minutes the Prefects held the field, but then the tide began to turn. Their opponents were still terrified, but in the crush a panicking beast was almost as dangerous one full of fight. The Prefects never slacked their furious assault but their ranks began to thin — at first slowly — then with sudden quickness. Giant rolling things with no heads and a forest of curved teeth smashed through them, and before they could regroup the horde fell on them.

Lanyard stood just inside the Great Door and watched waves of beasts sweep over the Prefects. Behind him the people of the Redoubt crowded close, their music stilled.

To A Mouse in the Walls of the Lesser Redoubt (Part 8)

© 2002 by Nigel Atkinson.

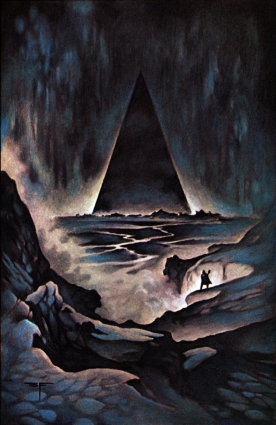

Image copyright by Stephen Fabian.