A Mouse in the Walls of the Lesser Redoubt (Part 2)

by

Nigel Atkinson

To A Mouse in the Walls of the Lesser Redoubt (Part 1)

Things were moving on the plain below the Redoubt. Summoned by bells, a dozen pairs of Prefects stood shoulder-to-shoulder, ready to repel any attackers. The Moramor watched wheeled things rolling towards the foot of Redoubt Hill, and the legions of beasts following in their wake. Grimly, he ordered reinforcements.

It was an hour before an attacker reached the apex of the pyramid. The Moramor despatched the creature with a coruscating slash of his Diskos. Battle was joined. A week passed before the creatures of the Night ended their assault.

The Gallowglass stood to attention just inside the doorway. From there he had a good view of the Master Monstruwacan’s Audience Chamber. It was an unusual room, even for the Lesser Redoubt. Decagonal in shape, its vaults dwarfed the people clustered on its floor and walls. On the two sloping walls adjacent to the door ten pairs of Prefects stood to attention. The four walls behind the Master’s dais belonged to the Monstruwacan Council. The benches were full today, with most of the two hundred and twenty-six council members present. Many of them were lolling back in their seats however, and it seemed that a few were actually asleep. Of the many innovations introduced by the young Lord of the Redoubt, Petitions Day was among the least popular.

Though not the most hated, the Gallowglass thought, the Master’s five-year-old decree requiring the acceptance of girls as apprentices, was still deeply resented by many. In his heart, the Gallowglass sympathised with the stick-in-the-muds who were holding out. Though women would never be introduced to the ranks of the Prefecture, the idea was deeply unsettling. He knew his duty, however, and had been quite ruthless in stamping out the few signs of outright resistance to the reforms.

The all-male Monstruwacans shifted uneasily in their seats (another unpopular innovation had decreed the removal of cushions), and glared balefully at the petitioners. The Gallowglass, who was naturally strong in the Night Hearing, suspected that their collective bile might be curdling milk all over the Redoubt.

The Master’s Clerk stepped forward and handed an Hour-Slip to his Lord.

"This petition is highly unusual," the Master Monstruwacan said after a brief glance at the slip. "I am surprised that that they managed to pursue it as far as my office."

The Clerk kept a blank expression on his face, but, when his lord's attention turned away from him, he shuffled a step away from the steel dais. Silence fell in the chamber as the Master silently read the petition.

The Lord of the Lesser Redoubt put the slip down on his lap and stared at the ragged bunch of postulants. Most of the half dozen men and women suddenly found something fascinating about their own feet. All except one, a woman with curled red hair. She kept her head high, and looked around the room with the air of someone who was determined to take in its splendours, whatever the cost. The Gallowglass wondered whether she appreciated the danger her impudence placed her in. For sure, many council members would have ordered her cut down already. He reflected that she probably had quite an attractive face, but her features were buried under a checkerboard of roughly applied, brightly-coloured face paints, making it impossible to guess her age. Her dress was clean, but ragged and festooned with bright coloured ribbons.

He was surprised that the Master had allowed the petition to get this far, but perhaps less surprised than anyone else in the room. Just two weeks ago, he had stood beside the man outside the Circuit of Assessment, while the child Naani was tested. The Master’s mental sigh of relief when the girl was found to be a true human was full of love and fear.

The Gallowglass looked at the woman: he knew her sort. In the records of the Prefecture there were histories reaching beyond the age of the Road Builders, to the shadowy origins of Mankind. The oldest texts were written in languages too antique to comprehend, but there were translations of translations of translations that recorded remarkably consistent ancient heresies. The cults described all had certain beliefs in common: a charismatic, conveniently absent leader who would come back one day to lead his followers to some ill-definite promised land, or who would rescue them from whatever evil was currently stalking them. Of course, you had to be a special person to benefit — someone whom the god especially loved, usually because he had been propitiated with payers and other offerings. The rest of humanity would be left to the tender mercies of the beasts.

He could put a name to this cult’s special little god — Harlequin — the enigmatic, mischievous will-o-the-wisp who had reached the apogee of his popularity three million years ago, before being wiped out in a bloody pogrom by one of his predecessors. He made a mental note to have the Moramor investigate the extent of the cult's influence. Most likely the handful of fanatics standing in front of him comprised the entire gang, but it was best to be sure.

The Master seemed about to dismiss the petitioners when the woman stepped closer. Astonishment rippled around the room and several council members shouted out. She stopped, her right foot almost touching the broad gold band that surrounded the dais. On it were inscribed the names of the thirty-seven thousand six hundred and fifteen Master Monstruwacans who had ruled in the eight million years since the Lesser Redoubt was raised.

The Master Monstruwacan help his hand up to stop her taking the fatal step, "Child, your persistence does you credit. I will judge your petition."

The woman fell to her knees. "Noble Lord," she said, "we humbly beg you to consider our proposal—"

A tall, white-haired Monstruwacan rose to his feet waving his fossilised wax staff of office.

"Enough of this! My Lord, why waste time on these low rascals? Be rid of them and let us consider more pressing matters."

"Master Beekeeper," the Master Monstruwacan said in an icy voice, "you have another appointment perhaps?"

"My Lord, of course not."

"Then sit down, this will not take up much more of your precious time."

The Bee Master sat down, hiding his anger by burying his face in a little flowering lithops he carried in a tapered terracotta pot that hung from a chain around his neck. The Gallowglass wondered exactly what ill odour his nosegay guarded him against.

The Master nodded to the woman. “Please continue,” he said.

"I speak on behalf of the doomed children, My Lord. Though they are ab-human, they are still innocents," she said.

"Yes, I have read your petition, child. What do you seek?" the Master said, shifting uncomfortably on his throne. It had been a long day. Unconsciously, he fingered the plain gold locket resting on his chest. "It is Law. On a child’s fifth birthday, it is taken to the Circuit of Assessment. If it is found to be ab-human, it must leave the Redoubt or accept mercy. Would you allow the creatures of the Night a foothold among us?"

"No, My Lord. We do not question Law's necessity. But, we humbly beseech you to let us give them the boon of a little training in wilderness craft, and . . . the mercy of Harlequin's teachings."

“That they will get pie in the sky when they die?”

“That is an oversimplification,” the woman said. She had to raise her voice to be heard over the Council’s laughter.

“Or will they have to wait for Judgement Day? That should be interesting, hearing your little God explain himself.” More laugher echoed around the chamber. The Master leaned forward. “He has twenty million years of mankind’s suffering to answer for,” he said.

The woman lowered her head, and shook it almost imperceptibly. The Gallowglass looked at her carefully. There was something familiar about her but, when he tried a mental probe, it slid away from the surface turmoil of her thoughts.

"You asked for them to be give wilderness training?” he said. “And where did you pick up such unusual skills? Surely you have not been outside the Redoubt? You know the punishments — especially for a woman."

"Yes, My Lord, and no, My Lord it has been time out of mind since our people sallied into the great darkness outside, but we have honed our skills in the monstrous caverns of the Country of Husbandry, far beyond the populated parts of the Redoubt."

"And what discoveries did you chance upon in the noisome dark?"

The woman raised her head and looked straight at the Master Monstruwacan.

"The Country of Husbandry is a place where men go as quietly as ghosts. The dreary souls, who come to take our dead on their last journey, are a tithe of the forgotten tribe who dwell there amid the silence. They have little ken of the rest of humanity, and less concern for our doings. Limitless, vast caverns are their domain and they guard their deepest places jealously—"

"Why? What is down there?" he demanded.

"I cannot say, My Lord. The followers of Harlequin only touch upon the fringes of the deep. We have no wish, or need to delve deeper. The places we know are harsh enough for the teaching of the skills. Harlequin teaches us that we should take only what suffices our needs, and give generously—"

The Master's patience evaporated. "So, in truth, you know little about the deep places of our world."

"No, Lord."

"You are dismissed."

"What about our petition?"

"Do not anger me further," the Master said. “Gallowglass!”

The Prefects sprang to life, spinning their Diskoi in furious salute as the Gallowglass marched forward. With a hand signal, he stilled his men’s electric fury and knelt before the Master.

"How may I serve, My Lord?"

"Rise, friend Gallowglass. I will have need of your council. First, please remove these people."

The Gallowglass made another hand signal, and two of his men advanced on the petitioners. In a trice the petitioners were hustled out of the room. The Master leaned back and looked at the ceiling high above. The minutes ticked by while everyone else waited for him to speak.

"Clerk," the Master said.

"Yes, My Lord," the Clerk said as he stepped forward.

“Stand there.”

“Yes, My Lord.”

"Gallowglass, I want you to investigate this cult," the Master said. He pointed at his Clerk. "This one is in league with them. Extract what you can from him. Then we will decide how to deal with that heretical rabble."

White-faced, the Clerk fell to his knees. Two Prefects moved swiftly and grabbed him, twisting his arms behind his back. They pulled him to his feet and started to drag him out of the hall.

"My Lord, I beg you," the Clerk shouted. "I care not what happens to me but, please, grant the petition."

"Even now, when you are condemned, you seek this boon from me?" The Master said, astonished.

"My life is as nothing, My Lord."

"Oh, very well," the Master said eventually.

Later in his private office, the Master Monstruwacan examined a diorama standing on an agate pedestal at the centre of the room. Inside a six-foot tall cylindrical diamond, Jackotrades had created an intricate representation of the Lesser Redoubt. Myriads of the tiny machines had carved subtle interference grooves and gratings that, when viewed from the correct angle, created the illusion of solid shapes and colours. At his eye-level, there was a miniature of the mile-high metal pyramid that was the only visible sign of the Redoubt. He looked closely, fancying that he could almost see tiny human figures at the apex. Under the pyramid, a long blue pipe fell ten miles into the Earth, and connected to a flat green disk, ten miles in diameter. This was where the bulk of the Redoubt’s population lived. It was where their fields, manufactories and homes lay. At the centre of the disk, a mottled green ball marked the Flying Wood, hanging over the Great Arbour. Blue tetrahedra signifying Guild Houses dotted the circumference, while a single red octahedron identified the Vault of Ages. Under the Arbour, a bright yellow band was cut into the native rock. This was Earth-Current generator — the source of all energy within the Redoubt.

He walked around the diamond and his perspective changed. The model of the Redoubt was replaced by a series of smaller images: the Pyramid standing on Redoubt Hill, overlooking the black plains below; details of the Stress Master’s engines in the central shaft and beyond — none of them interested him. He changed his position again; this time finding images of the fringes of his domain — the Country of Husbandry — and the dubious lands beyond.

As he examined these unknown regions an old quotation came to mind — here be dragons — and a tear trickled down his face.

Filangeri the Stress Master herded the passengers onto the granite disk. He wasn't in a good mood. Normally he would have left such a task to a minion, but an Hour-Slip signed in the Master Monstruwacan's own hand had demanded his participation.

Transporting ab-human children to the fringes of the Country of Husbandry was tedious and distasteful to him. The boy appeared normal enough, except for his perpetual smile. The religious woman frowned as he instructed her in the proper protocols. The two Prefects escorting them simply ignored him.

Filangeri prodded a flake of something blue that was resting on the burnished control panel. The woman's face and arms were covered in multi-coloured daubings, and he had no doubt where the guilt lay. Fastidiously, he moistened the end of a finger and picked up the flake. His passengers were looking strangely at him, probably wondering why he didn’t leave such a minor imperfection for the Jackotrades to clean up. He ignored their stares; he didn’t trust the little machines to do a thorough job.

He instructed the passengers to grab firm hold of the handrail that sprouted from the centre of the disk. Typically, the Prefects declined, settling for grounding the butts of their weapons for balance.

"Please hold on tight," Filangeri said. "The ride is long and can make some people a little nauseated. We will start now."

He pushed a brass lever, and the granite cylinder they were standing on began to fall. At first the movement was slow but, once the embarkation room was clear, the pace picked up. The smooth walls of the pipe became blurred with speed as the platform plunged downwards. Filangeri fussed over his instruments — speed, vibration, air pressure, temperature, static electricity — all were within accepted limits. There was a chattering of hour printers as the cylinder flashed through a junction. Filangeri scanned the slips quickly. Everything seemed in order. Back at the central nexus, his minions seemed to be doing their jobs adequately.

But he couldn't help but worry. The adjustment of forces needed to maintain the equilibrium between ascending cylinders with descending ones, and the balancing of hundreds of tonnes of moving rock and miles of stretching, articulating metal, was a subtle skill only understood by a master like himself.

"How long?" The woman asked.

"We will soon reach the first airlock," Filangeri said without turning.

He tilted his head. There was a noise. It was nothing really, just an overtone in the pure note generated by the cylinder's fall. He tapped a dial, wondering if there was a problem with the vertebral reciprocating assembly.

"Stop that at once," the woman said.

Fuming, Filangeri spun round ready to replay her presumption with scalding invective. Then he saw what the real problem was. The boy had left the handrail and, quite incredibly, was standing at the edge of the disk poking a hand in the stream of air dashing through the finger-wide gap between the wall and cylinder. Filangeri was apoplectic.

"Stop that at once, boy!" he stammered.

The boy giggled. He knew no one would stop his little game until the ride was over.

The bodies were arranged in a neat row. Two Perfects and a corpulent man whose fine clothes had been ruined by the blood that had flowed from his cut throat. The bodies were several days old and the younger Prefect, although standing stiffly to attention, was visibly fighting the urge to gag. The Moramor made a mental note to arrange for suitable training to rid him of this foible.

Small cloth dolls had been found resting beside each body. The Gallowglass twirled one of them in his fingers. They were colourful but crudely made from scraps and coarse thread.

“The Harlequin sect?” the Prefect asked.

“Start the hunt,” the Moramor said.

The Gallowglass was uncomfortable. He was used to the sharp angles and smooth surfaces of the Prefecture. The Master Monstruwacan’s home had shaded alcoves and curtains. A bowl of peppermint comfits stood on a sandalwood table.

Somehow, despite knowing that the Master had a child, he had not expected her presence to so influence his Lord’s home. Bowls of petits pois scented the air and a set of wooden alphabet tiles had spilled from a low table onto the floor. Their five-year old owner sat on her father’s lap, and was scowling.

"It's not fair!" she said

"No, it isn't my sweet," the Lord of the Lesser Redoubt said. "But I have business of state to deal with. Here's Tanna, go with her. It's getting late, I'll come by to tuck you in later."

Naani stuck her bottom lip out. "Don't want to be tucked in."

"Oh, now what a thing to say," the maid said, as she swept the child up in her arms. "Don't you worry, My Lord. This little one will be on her best behaviour when next you see her."

"Don't chastise her too much; I did promise to play with her this evening."

The maid curtsied, and herded Naani out of the library. She glanced at the Gallowglass as she left, then looked away quickly.

“Gallowglass, please come in,” the Master said.

He limped in and knelt on his right knee before his lord, placing his Diskos on the floor beside him. His armour was splattered with dirt and dry stains that might have been blood. There was tang of ozone in the air, a sure sign that he had been in battle, and his face was grim.

"Is the rebellion dealt with?" the Master asked.

"I would hardly call it a rebellion—"

"I did not ask for your analysis of the political situation, Gallowglass. Have the heretics been put down?"

The Gallowglass shifted his position and rested a hand on the floor for a moment before answering.

"Yes, My Lord. Half of the sect members were taken alive, and are being put to the question as we speak."

"How many in total?"

"Seventy-six."

"Seventy-six? So few, yet they had the confidence to resist your investigations and, when you hunted them down, stand and fight? You are slipping, my friend."

The Gallowglass bowed his head. "I beg your forgiveness."

"Did you find the ab-human boy or the woman?"

"No, My Lord, nor any evidence of their accomplices. But for sure there must have been others, a small boy and a woman could not overcome two Prefects.”

"Did you find any evidence to link the cult with the murders?"

The Gallowglass held up a small rag doll. "This token of their sect was found with the bodies. It is more than enough to condemn them all."

"Yes, I suppose it is," the Master said, imagining the fury of the Prefects when they discovered the killers of their comrades. Something in the Gallowglass' expression caught his eye.

"There is something else?"

"Yes, My Lord. Our investigations of the Stress-Masters Guild turned up an interesting Hour-Slip. It held an order for Filangeri to escort the ab-human boy to the lower chambers — seemingly it was signed by you — the sigils upon the slip are almost indistinguishable from the real ones."

"That is impossible."

“Apparently not,” the Gallowglass said dryly. “The Stress Masters deny that they have any record of the Hour-Slip passing through their hands. They offered to open their achieves to me, the better to prove their innocence. I declined. If they are capable of forging your sigils, hiding a paper trail would be of little difficulty.”

“What do you want to do?”

“I would like to kick the doors of the Stress-Masters' Guild in and tear the place apart until I found answers.” The Gallowglass paused for a moment, perhaps waiting for his Lord to speak, before continuing. “But that is impossible. The Guilds hold their secrets tight under ancient laws. We must seek other sources of information.”

“You have my full confidence, Gallowglass,” the Master said, with a tone of dismissal in his voice.

Bergthora watched as the Master ran his hand over the sandstone wall.

“Is this room secure?” the Master asked.

“The walls are lined with Jackotrade-filled capillaries, My Lord,” Bergthora said. “We are hidden from the mental sight of your fellow Monstruwacans. Are you afraid that they suspect something?”

“Not really, they always suspect something, lack of trust it is in their nature. With the murders—”

“Surely that is a matter for the Prefects? Aren’t they who we should worry about?”

“I can deal with the Prefects. Their straightforwardness makes them easy to manipulate. I laid a false trail leading into the heart of the Stress-Masters' Guild.”

“That’s clever.”

“Thank you.”

“I wasn’t being sarcastic, My Lord. The Prefects could beat their heads against that immovable object for weeks and still be no wiser. The capacity of your mind is not in doubt — after all that is why you are the youngest Master in recorded history.”

“No it isn’t,” he said under his breath, his face turned away from the woman.

“Did you say something?”

“I do not know whether I did the right thing.”

“In trusting me?”

“In not having your son cast out of the Redoubt as Law demands. He failed the Circuit of Assessment, so I doubt he is worthy. In any case, there is a better than one in sixty chance that he is not the child I seek.”

Bergthora noticed that he had not answered her question about trust. “That calculation has always been true. Yet you let him live. Your intentions were noble,” she said.

“You do not know anything about my plans, and do not talk to me about good intentions — you are his mother.”

“And you are complicit in the murder of two Prefects and a Stress-Master, not to mention a conspiracy to hide his survival, and you just ordered the deaths of over seventy members of my faith.”

“You would blackmail me?”

“Of course not, My Lord. I am forever in your debt. I merely point out that our paths are inextricably linked.”

To A Mouse in the Walls of the Lesser Redoubt (Part 3)

© 2002 by Nigel Atkinson.

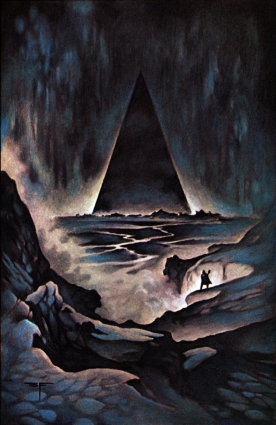

Image copyright by Stephen Fabian.