A Mouse in the Walls of the Lesser Redoubt (Part 5)

by

Nigel Atkinson

To A Mouse in the Walls of the Lesser Redoubt (Part 4)

Caliban attacked the wall with bare hands and booted feet. The air was full of pulverised rockplug, but still he hadn’t hit the other side. He could hear the Prefects getting closer, their heavy footsteps and angry shouts echoing up the wide spiral stairway that curled around the shaft connecting the pyramid with the caverns below. They had been hunting him for two hours, ever since the Watchmaker had chased him from his shop. Caliban cursed him — he would make him pay for all this trouble one day.

The man had looked up from his work suspiciously as Caliban walked into his workshop.

“What do you want, boy?” he demanded, pushing his loupe back behind his head. “Shouldn’t you be in school at this time?”

Caliban coughed into a silk handkerchief. “I’ve been ill for some day with an ague.” The Watchmaker edged back a little. “But, I’m better now and mamma suggested I go for a walk. She’s been a wonder looking after me while I was ill, so I though I might buy her a thank you gift, something in silver, perhaps—”

Caliban left the bait dangling, but the Watchmaker was still suspicious.

“Your mamma?

“Lady Bergthora Baumgard,” Caliban said with little in the way of nonchalance.

The Watchmaker’s eyes brightened greedily. “Well, yes, maybe I have some small pieces that might interest her, I mean you, My, ahem, young Lordship.”

The Watchmaker showed him a range of intricate and expensive timepieces. Caliban turned the watches and small clocks over in his hands, while the man droned on about their mechanisms and cunning complexities. The boy nodded occasionally, but paid no real attention to the craftsman’s witterings. He was much more interested in the tiny electric tickling in his fingertips as the Jackotrades bled through his skin. The sensation of control was delicious. Often recently, it had seemed as if the little machines that permeated his flesh were working to a will of their own. But, when he woke up that morning, he knew that this was going to be a good day, a day when he was in charge.

“Well, young Master. I was wondering—” the Watchmaker asked, nervously. He had a slender sandclock in his hands. It was made from tiny twisted ropes of gold and silver, and its pivots had onyx and agate seatings. Despite its relative inaccuracy compared to mechanical clocks and watches, Caliban guessed that it was the most expensive timepiece in the shop.

“I won’t be buying,” Caliban said.

The Watchmaker’s face fell. “May I ask why not?”

“Because your clocks don’t work.” He pointed to the first timepiece the Watchmaker had showed him. “That one seems to have seized up.”

The Watchmaker picked up the clock and looked at it incredulously. He tipped his loupe down in front of his right eye, and opened the back of the clock with a small tool that he carried in his sleeve. His face turned red as he twiddled screws and nudged tiny springs.

“Is it broken?” Caliban asked.

The Watchmaker shook his head. “No, I can fix it. It’s nothing.”

Caliban patted him on the back. ”That’s good to hear. Especially since all your other pieces seem to be broken too — oh except for the sandclock — pity it’s so gaudy — not quite right for a Lady’s home, I think.”

The Watchmaker ran his trembling hands the rest of his ruined timepieces; then he looked at Caliban with a mixture of disbelief and hatred.

“You did this?” he snarled in a tiny, choking voice.

Caliban winked and ran from the shop. After a moment the Watchmaker ran after him. That wouldn’t normally have been a problem; Caliban was fast on his feet and knew ever nook and cranny of the Redoubt. However, just as the man burst into the street, flinging curses and shouting for help in a surprisingly loud voice, a squad of Prefects turned the corner.

Caliban took his pursuers on an epic and exhilarating run through the Craftsman’s district, in and out of the Shambles and around the Great Arbour. He felt like he was flying over the short red grass, but the Prefects never gave up. In fact, more of them joined the chase. By the time he reached the rarely used tunnels that surrounded the Arbour and led up to the Stress-Masters' domain, a dozen Prefects were hunting him. A detour into a ventilation pipe lost them for a while, but they soon caught up with his trail again.

Now they were only minutes away, and he had nowhere left to run to.

Cursing, he backed hard up against the sandstone wall and balled his fists. The hunters were almost upon him. Sweat poured won his face and his breath came in rasps; they had him this time.

Then he took another step backwards.

The workshop was a shambles. Hundreds of jars were broken or spilled, ten-foot high mahogany shelves dripped with viscous fluids, notebooks were sticky with black ooze, and the floor was covered with broken glass. The Moramor prodded a jar of binder Jackotrades. Shattered into a countless fragments, it was held together by its sticky, dead contents. He gave it tap, and the jar gave way, slowly slumping down into a glutinous, glass pierced heap. It was the same all over his workshop: The only part of the Jackotrade Master’s arsenal that was undamaged was the collection of tinctures and potions used to guide the tiny machines to their tasks. The Moramor leaned forward and sniffed the rows of undamaged jars. They smelled of sharp acids and oils.

“And you found the damage this morning, yes?” the Moramor asked.

“Yes, My Lord. I opened up as usual this morning,” Hugh replied. “Well, to be truthful I was a bit early, you see I was going—”

“He doesn’t need to know that,” Hugh’s wife interrupted.

“Yes, he does, he needs to know everything, don’t you, Sir?”

“Well, perhaps not everything,” the Moramor said, dryly.

“Told you.”

“Be still, wife,” Hugh said.

Essa folded her arms and fell silent. From the look on her face, the Moramor doubted that she would stay that way for long. He listened politely as Hugh blathered on about his duties. It was becoming an increasingly familiar tale. Mysterious acts of vandalism were happening all over the redoubt — a plague of maggots in the cheese bazaar — Hour-Slip tubes gummed up with cob nut husks — slippery, hard-to-see oil on the shaded paths under the Flying Wood. He knew full well who was responsible, but catching the culprit was easier said than done. Just yesterday, he had led a squad of hunters into the wide spiral stairways that curled around the shaft connecting the pyramid with the caverns below. At first the boy’s trail was easy to follow — he had kicked his way through the soft rockplug seals blocking the stairs — but then all trace of him disappeared apart from a pile of thinly shredded clothes.

The Moramor picked up another broken jar. Whatever had happened here, it wasn’t the feral boy’s work. Something subtler was at work here.

Caliban screamed incessantly during the thousands of years he was entombed in the wall. It made no difference; the rock was indifferent. Blazing agony coursed through every part of his being but, although most of his consciousness was lost to howling, a tiny, rational part calmly analysed what had happened. Before he abandoned such unnecessary activities, he had been a reasonably attentive student. He remembered being told that he was a coalition of trillions of tiny cells, and inside each cell there were legions of symbiotic organelles, all busy with their own evolutionary agendas while helping him through life. It seemed absurd to him, and at the time he didn’t care.

Being dragged into solid rock had sharpened his interest in the nature of life.

He had been squeezed and stretched — each cell separated from its neighbours and spread over the infinity of the rock universe. Despite the diaspora, something was holding him together. After untold ages, he realised that he could will his separate parts to flow. At first his reformation was agonisingly slow, but gradually the pace quickened and he fell from the wall. It was a long time before he stopped screaming. He lay naked on the cold stone floor unable to remember who he was. The puzzle was almost beyond him, but he finally remembered.

He was Caliban, and he was special.

Monstruwacan Lindos wandered through the Great Arbour in something of a trance, his mind filled with cubic splines and partial derivatives. So intent had he been on his books and abaci, that only the emptiness in his stomach told him the best part of the day had passed. Reluctantly, he decided to walk to the Shambles in search of a pasty or sweetmeat. Pleased at his sudden burst of practicality. Lindos stepped into the nearest shop. A woman was berating the Baker. Lindos began to edge out of the shop, but she spotted him.

“A Monstruwacan, ha!” she said. She picked up a loaf and brandished it at him. "Look at this! Every loaf ruined. It's been the same all week. Perhaps is you lot got off your fat backsides and brought your precious Master—"

Lindos pushed the loaf away from his face with his outstretched fingertips. It was covered in a vivid red fungus and smelt of sweet decay. The woman shoved it back. Lindos desperately wanted to get away from her. He turned to leave but found that the door was blocked by several people. They pushed into the shop forcing Lindos back.

"I’m sure the matter is under consideration, Madam. The authorities are—" Lindos blurted.

"The Authorities — lot of good they are — couldn't find their own arses with both hands!"

The fast growing crowd laughed. Lindos wasn’t sure what they found funny. It was so unfair; what had rotting bread to do with him? He knew something was up; anyone who had a glimmering of the Night Hearing could sense the growing irritation and worry throughout the Redoubt. The stability of their world was fraying at the edges, taking many certainties with it. It was only little things really; food corrupting in hours not days, an unexplained fire that left half-a-dozen undercriers nursing burns, a plague of nasty, biting mosquitoes in the public baths, and a dozen other minor irritations. Each incident would have been unremarkable on its own — things go amiss in even the best-regulated societies — but, with so many things going wrong at once, tension was growing.

"I am so sorry," Lindos said.

"Sorry isn't good enough!" someone shouted.

Other angry voices joined the complaint. The crowd surged forward, Lindos tried to run, but they were soon upon him.

Four hours later word of the incident had reached the Gallowglass in his Keep.

"A Monstruwacan beaten!" He crushed the report in his hand. "Where were our men when this mob was loose?"

"Our numbers are few, we cannot be everywhere—" the Moramor began.

"I am not interested in excuses, I want the culprits hunted down. I will personally flog every one of them. A Monstruwacan beaten! Never in the annals of the Prefects has such a thing happened. If this spreads we will have anarchy on our hands — or civil war! Never have we fallen so low!"

"The offenders are being sought, My Lord. They will be brought to justice. But—"

The Gallowglass sat down, and spread the crumpled papers on the wooden table in front of him. He looked at the reports lying on jet-black wood. "Our numbers are few, and problems multiply by the day," he said.

"Yes, My Lord. Fouled water in the Eastern terraces, fires in the News Crier's Guild House, the strange behaviour of the Jackotrades—"

“What news on that?”

“I am meeting with someone from the Jackotrade Guild later today. Perhaps he can shed some light on the events. Their Guild House must be in ferment. They are being tight-lipped, but I have determined that at least a third of their Masters have lost their stocks in the last month.”

“What is the people’s mood overall?”

"They are afraid, My Lord. Rumours are spreading like lice."

"Rumours?"

"That the dark forces have found away into our home, that something malign slinks though the gaps behind our walls, working mischief wherever it goes. That Guild system is falling apart, and that—"

“Out with it, man.”

“People say that the Master Monstruwacan spends all his days lost in the Vault of Ages, searching desperately for some miraculous way to stop the End of Days.”

“That is an . . . exaggeration, nor is this is not the End of Days.”

“Maybe not. I have no knowledge of such things. I do know that the Monstruwacan Council has not met for six years, and that they fester at their impotence, and that the Guilds—”

The Gallowglass’ voice fell to a whisper. “Enough! You stretch the bounds of our friendship to near breaking point.”

“My Lord, I was not speaking to you as one who loves you, but as your second-in-command,” the Moramor said calmly.

The Gallowglass flinched as from a slap, looked into his friend eyes and nodded sadly. “You are right. The public mood is a legitimate matter for concern, and I will raise it the Lord of the Redoubt.”

The yellow, blue and red abstract shapes projected onto the curving wall reflected in the vitreous armour of his squad. Whatever way he looked at the images, the Moramor could make nothing of their rough-hewn geometries.

"What am I looking at?" he asked, hoping the girl had not realised how flummoxed he had been when she had turned out not to be the man he had expected.

Theodora looked up from her instruments. She was sitting in front of a tall silver tower festooned with dials, ratchets and eyepieces. Dozens of similar gadgets were scattered on wooden workbenches.

"Ask your men to leave," she said.

"Why?"

"I can hardly tell why they need to leave while they are still here, can I?"

"Your reasoning is impeccable," he said, as he dismissed his men with a hand signal.

Theodora waited as the Prefects spun on their heels and marched quickly from the room, then stood beside the projector.

"This picture is magnified near two thousand times. The large irregular, red-black particles are ferric oxide, rust, if you prefer," she said.

"You mean corrosion? That is impossible. The Jackotrades should repair any damage before it becomes a problem."

"Evidently not, “ Theodora said. ”You see the small yellow objects?"

He nodded.

"They are redundant Jackotrades."

"By redundant you mean dead?"

"Yes."

"My knowledge of such matters is scant. I understand that they live, if that is even the right word, for but a short time, then die after which their essentials are used to fashion subsequent generations."

"All of the samples your men collected in the Long Galleries are filled with dead Jackotrades — and none that are living."

"Oh."

"You have a gift for pithiness, Moramor."

"You find this humorous?"

"The end of our civilisation and the Fall of Night? Strangely, I don't find that funny. Look, there is another sample you should look at. This is from the inside of one my Master’s jars."

She fiddled with her microscope, opening doors, pushing and pulling slides, peering down optics and twiddling with knobs, working to sharpen the amorphous green blur on the wall. Finally, the image clarified into something that looked like holes in cheese. She reduced the magnification, and the holes began to form a pattern.

“That almost looks like—” the Moramor began.

"The Jackotrades tunnelled their way out," she confirmed.

“Why would they do that?”

"That is an interesting question, and the only answers I can imagine terrify me."

Just to the east of the Shine lay the desolate landscape called the Place of Gas. The thin zephyrs that whistled across the Night Land made no impression on the miasma of death that hung about the place. All but the most brutish of Night’s inhabitants knew better than to enter the killing zone. The boundary was easy to see: the wretched scrubby vegetation that somehow had found a foothold in the Night stopped at the edge, as if it had run into an invisible wall. Just inside the boundary, there was a ring of bones, bleached and pitted by the corrosive air.

Something was happening in the Shine, and it was drawing the creatures of the Night towards the deadly zone. Beast men and more unspeakable things stood in a widely spaced line around the Place of Gas. They shook with terror and howled defiance at the vague shapes coalescing amid the blue glow. Creatures with hands or claws grasped rocks or bone clubs; the others bared their teeth or unsheathed claws.

The Master Monstruwacan sat cross-legged at the centre of the Vault of Ages, surrounded by dozens of pieces of paper; each one covered in his precise handwriting and tiny drawings. He picked one up, scrutinised it carefully, then put it down and picked up another. He read the entire collection six times before he was satisfied.

After sixteen years fruitless searching, he had finally found the blueprints for a Master-Word machine.

His wiped the rheum from his eyes, and took a draught of stewed madder root tea. Three days had passed since he had last slept, and he hardly noticed the stimulant’s bitter taste and pungent overtones. Twelve hours had passed since the unexpected harvest from the Search Engines had dried up, but only now did he dare consider leaving the Vault. He had no idea why the machines had suddenly found the secrets he search for so long and, even when he had finished transcribing the wonderful secrets they had found, was reluctant to leave in case they other revelations for him.

In the end the well dried up —- but he was satisfied — now he needed to decide what to do next.

Bergthora and the Master were alone in his Audience chamber; even the Prefect honour guard was absent, called away to deal with some trouble nearby. The Master sat on his dais, and listened dispassionately to Theodora’s news.

“There is no possibility this is wrong?” he said.

“The facts have been checked, and checked time and again,” she said, her voice echoing around the undamped spaces of the Audience chamber. “The native Jackotrade colonies are migrating. At this rate, in ten years, the pyramid will be devoid of them. In two hundred they will have abandoned the Redoubt.”

“This is . . . unusual news you bring me.”

Exasperated by the Master’s strange mood, Bergthora felt a sudden urge to race up the dais steps and slap his face, but before she could the chamber’s doors slung open to admit the Gallowglass. His booted footsteps cracked and reverberated around the chamber as he marched towards the dais. A tang of ozone clung to him and a livid bruise covered half of his face. He bowed perfunctorily to the Master, and ignored Bergthora.

“My Lord! Things are coming out of the Shine, the Jackotrades are deserting us, and the people are in ferment. What are we to do?”

The Master stared into the Gallowglass’ eyes then, after a long moment, he embraced the soldier, and then pushed him away gently. He nodded gravely. “You are right, Gallowglass. These are unprecedented times. We are assailed on all sides and from within. But there is hope. It is time to make decisions that have been put off for too long.”

“Decisions?”

“Yes, in particular there is a final reform I want to put in place — the creation of a new Guild.”

Bergthora looked at him with sudden understanding in her eyes. He shook his head, and she kept her peace.

“This new Guild will be given a great task,” the Master said. “Trust me, old friend, there is hope that, whatever happens, something true will survive.”

“You are talking about the Final Battle,” the Gallowglass said.

Bergthora stood beside the Gallowglass. “Tell him everything,” she said. “He deserves to know what he may be asked to die for.”

The Gallowglass hardly noticed the ice-laden wind whipping his face. Far to the South the blue glow from the Shine was laced with red and silver. Waves of distress pulsed from it and battered the Redoubt. All of the Watchers were cowering below the battlements, but he was pleased to see than none of them had left their stations. They would recover their courage soon enough, until then he and his Prefects would keep the watch. His men were stone-faced and unflinching, but he could sense their inner torment.

Even the truest can be daunted — and can die.

The Master had spent an hour telling him about his enKernelling, and explaining why the children had been brought together. Oddly, the Gallowglass found the end of the Redoubt easier to accept than the idea that a child held the secret to the survival of humankind.

“I am a soldier, show me something I can fight.”

One of the Watchers heard his whispered comment and looked up puzzled.

The Gallowglass squeezed the Watcher’s shoulder. “Don’t worry, my friend. I was just gathering gossamer threads to make a coat of wishes.”

The Watcher looked unconvinced, but smiled bravely and, after a deep breath stood up and took his place at a loophole. Soon after, the rest of his Watch joined him in facing down the hurricane of hate howling across the Night Land.

“He goes too far this time!” Cambyses shouted as he burst into the room.

Lanyard looked up from the game of Congkak he was playing with Argus. Cambyses was out of breath and waving a sheaf of Hour-Slips.

“Good day, Master Cambyses,” Lanyard said as he scooped up a handful of beads then spilled them smoothly one-by-one into Argus’ Southern houses. His opponent pulled a face and rested his chin on his wrinkled hands. Recognising this as a sign of a lengthy analysis Lanyard turned to face Cambyses. “And what has our esteemed Master Monstruwacan done to annoy you on this day, Master Cambyses?”

Cambyses pushed the Hour-Slip under Lanyard’s nose. “Read this! You won’t believe what he has done this time. He’s only proposing setting up a new Guild House, and filling it with a bunch of children — some of them of peasant and artisan rank.”

For all his comical bluster, Cambyses had gained Lanyard’s attention. Even Argus looked up for a few seconds before turning his attention back to the game. Lanyard took the Hour-Slips and carefully read them.

“This is unusual,” he said eventually.

“Unusual? Unprecedented would be a better word. The Monstruwacan Council should meet to discuss this.”

“Well, wouldn’t that be a novelty. What is it — seven years — since we last met? Perhaps you would like to petition the Master on this matter, Master Cambyses?”

Cambyses shuffled his feet.

“Precisely,” Lanyard said.

“Something must be done,” Cambyses hissed, looking around nervously as if expecting the Master to leap out from behind the arras. “He refuses to let us meet or advise him, spends all of his time either with that woman of his or the Gallowglass — and the rest of his days searching in the Vault of Ages — and now this! The people will be unhappy, I can guarantee that.”

“Yes,” Lanyard said in a chilly voice. “I’m sure you can.”

Cambyses’ expression flickered angrily for an instant, and then he snatched the Hour-Slip back and stormed out of the room. Lanyard leaned back in his chair and pondered the implications of the news. Cambyses might be a slinker, but he had the ears of the leaders of several Guilds, and was bound to make a bad situation worse. A soft tapping disturbed his concentration, and he looked up in time to see Argus’ shaking fingers flick a dozen shells into the diagonal houses, and four into Lanyard’s own. The old man grinned happily.

“Game’s over,” he said.

The Shine was tormented like a volcano chained at the instant before eruption. Entities trapped for aeons clawed at their bonds and rent the Night with their frustration. But the ancient bounds held fast, and the captives finally admitted defeat and slumped into bitter silence. Outside the Shine, the death zone stretched for tens of miles. Hundreds of beasts lay dead or dying, their souls torn and scattered into the endless Night. The husks of snaggletoothed harpy worms lay everywhere; supremely hardy lichens had been reduced to carbon; rock-burrowing bacteria and slimy, thick-walled protozoa had been consumed from the inside out.

Inside the Redoubt day began after a night tortured by terrible nightmares — even for the majority of who had found no sleep. Bleary-eyed people comforted each other as best they could, although nothing could be said that would take away the terrible memories. When the Redoubt slowly got about its business they began to find the victims. A hundred people had died or taken their own lives during the psychic onslaught. Later, when the initial shock was over, the talk turned to revenge and responsibility — what were their leaders doing to allow such a thing to befall them? With drink inside them, a few bold if ill-equipped souls demanded to know why the Prefects and the Master Monstruwacan weren’t spending more effort devising strategies to fight the Night terrors.

“Surely the Redoubt can defend itself?” they asked resentfully.

Which was somewhat ironic because lying among and within the dead of the Night Land were countless blasted microscopic metallic husks — unacknowledged fighters from the Lesser Redoubt.

The Guild-House smelled of new paint and wood polish, but the walls were made of strong steel and Prefects guarded the entrances. Naani couldn’t decide whether the Prefects were there to keep people out, or keep the children in. She had been one of the first to arrive; an hour later there were nearly sixty of them — all around her age. She knew a few of them, but was surprised at how many of her contemporaries she had never met. A tall blonde girl, who spoke with a strong farmer’s accent, asked her if she knew what was going on. Naani shook her head, feeling obscurely grateful that the girl did not recognise her.

“Took me away from my work,” the girl said. “It’s brambling time to — they be plenty of cuts and scrapes to treat, and me stuck here.”

“You’re a healer?”

“Just a third-ranker so far, and I don’t see how coming to this place is going to improve my skills. Oh, by the way, I’m called Arian, and you are—”

A small freckled-faced boy joined them. “Naani, what’s going on here? I was practically dragged out of my Guild House — you should have seen the look on my master’s face when the Prefects arrived.”

“You’re the Master’s daughter?” Arian asked.

“Someone has to be,” Naani said too quickly. Arian’s face flushed like she had been slapped, and she turned around and walked away.

“Wait, I’m sorry”, Naani called after Arian, but she had disappeared into the crowd.

“She’s tetchy,” Aldous said. “Anyway, do you know what’s going on here?”

Before Naani could answer, a Prefect sounded a short blast on a bugle. “Give your attention to the Master Monstruwacan,” he shouted.

The undercurrent of chatter in the room stilled, and everyone looked towards the small stage at the back of the room. The Master walked in accompanied by a red-haired woman, whom Naani didn’t recognise, and the Gallowglass. Naani sent a brief mental greeting to her father but, if he heard it, it was ignored. Several weeks had passed since she had last met; when she looked carefully at him, it seemed that he had aged ten years since then. His face was drawn and his eyes tired, but when he spoke, his voice had all of its old resonance.

“Greetings — and welcome to your Guild House.” A brief hubbub of surprise rose among the children. Then their discipline asserted itself and they fell quickly silent as the Master continued. “You have been chosen to found a new Guild, a Guild to span all the Guilds. Many of you have spent the last two years as apprentices and most of the others have been following special teaching programmes designed to make them ready for this new challenge. For too long the people of the Lesser Redoubt have dully followed paths lain down aeons, in some cases millions of years, ago. The old ways will not serve us any longer. There are great problems facing us, problems that have not yet been revealed to the general population. It will be your duty to face these problems head on, and create solutions that would have been unthinkable before.”

He paused as if trying to gauge his audience’s reaction. They just looked back at him in stunned silence. For an instant his eyes met Naani’s and she saw into his heart. Several moments passed before she realised that he had started to speak again.

“I have a special task that will let you to show your mettle,” he said. “A task that has been impossible until now. Impossible for two reasons. Firstly, I only recently discovered the way of doing this thing. Secondly, the wide range of skills needed do not exist in any single Guild, and the existing Houses are too fractious and divided to come together for this task.”

He paused again then, at the perfect moment, continued. “I want you to build a new Master-Word machine.”

The room erupted in cheering and amazement. The Master held his hands up for quiet. When that didn’t work, the Prefect’s bugle was blown long and loud.

“There will be time for questions later,” he said. “For now, you should settle into your new home.” He gestured to the woman at his side. “Lady Baumgard will describe your domestic arrangements, dormitories and rules and such like. I will speak to you again later.”

The Master left without a glance at his daughter. She knew why; she had seen into his soul and knew that, in some fundamental way, he was lying.

To A Mouse in the Walls of the Lesser Redoubt (Part 6)

© 2002 by Nigel Atkinson.

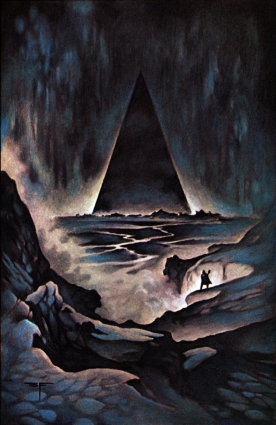

Image copyright by Stephen Fabian.