An Exhalation of Butterflies

by

Nigel Atkinson

The two hundred and fifteenth echelon of the underground country was, in Loomis' not-completely unbiased opinion, the most beautiful of all of the underground lands. He rested his hands on the balustrade and gazed down on the patchwork of farms and spinneys half a mile below his feet. The scents of poppies and ripe wheat rose to meet him. He sniffed deeply, and became aware of the bakery halfway up the pillar that supported the Lepidoptery — there would be fresh mushroom and bilberry pasties this afternoon. He decided to investigate them later. Loomis leaned forward tentatively, then pulled back at once. Heights were not his strong suit.

As he mustered his dignity, he became aware of someone standing next to him. He looked down. An apprentice boy stood there. Loomis did his best to ignore him, and turned his eyes towards the buildings that barnacled the rim of the nearest of the seventy-five lesser light wells. The well was five miles away, but it was just possible distinguish individual premises. Brightly coloured refectories and tailor shops from whose windows trailed gaudy flags and pallia dotted the higher parts of the wall. Lower down were the dormitories of the auxiliaries who worked the well's baffles and prisms.

Loomis' eyes turned to the waterfall of light pouring down the well. Today, it seemed to him that the scintilla of the Earth Force was rising from the well. That was a common optical illusion. The intellect knew that the light was cascading down from the Earth Current-kindled luminary a hundred miles above, but sometimes the eye chose to disagree.

Loomis glanced to his side; the boy was still there.

He adopted his most imposing stance. "What do you want, lad?"

"How old are you, Master?" The boy asked. Loomis leaned on his pollen broom and brushed away the clump of Red Admirals that were dancing on his pollen stained brow. He attempted to pierce the boy with a flinty look. It seemed to have little effect. The youth of today, he thought. In my day we had respect for our elders.

"I'm exactly the right age I should be, Apprentice."

The boy persisted. "And what's that?"

"Old enough to give you a clout, manling."

The boy shrugged. "And then will you tell me how old you are? They say you are a thousand years old — at least!"

The lad's ear was a tempting target. But for once Loomis didn't have the heart. In truth, he was quite amused by his determination. Not that he would admit that of course. Curiosity was all right in its place, but too much of it always led to trouble. He could vouch for that. But, he still had some sense of duty left. The mysteries of the Lepidoptery were only part of what masters must teach the apprentices. Due deference and a respect for the natural order were also important, if less academically demanding.

Loomis nodded towards the clump of apprentices who were circling round Mistress Melrig at few dozen yards further along the gallery. "I'm old enough to wonder why you aren't attending to your studies with the good mistress yonder." The boy bit his lip and discovered something fascinating about his bare feet. He wriggled his toes in the thin layer of discarded scales that covered every surface in the gallery. Loomis wondered whether he was trying to taste the floor with his feet. Many a young apprentice tried that trick, after the mystery of where their charges' tasting organs were had been revealed to them, but the boy seemed too old for that particular silliness.

Loomis estimated the he was about twelve years old, almost old enough to take his name. Almost as old as his son had been … Putting the old wound aside, he turned his attention back to the boy.

"Well?"

He shuffled his feet. "She's, y'know."

"Enlighten me."

"A bit, um, dull."

Loomis wrinkled his brow and peered over his nose pouches at the boy. He tended to agree with the apprentice's assessment of Mistress Melrig. As far as Loomis was concerned she was the worst fusspot in Wrangwysh Toft Lepidoptery, and quite possibly in the entire Great Redoubt. She's probably boring her poor students half to death, he thought. But, all that said, she was a sister of the guild, and it would not be seemly to allow such criticism to pass unscathed.

Loomis' hand was fast enough to pluck a butterfly from its darting, twisting, unpredictable path. So the boy never had a chance of avoiding the retribution that came to him in a blur of precise motion.

"Ow!" The lad exclaimed as he reached to comfort a painfully twisted ear lobe. "That hurt!"

"Consider yourself lucky. I'm in a benevolent mood, otherwise I'd have pulled your ear right off."

From the look on the boy's face, Loomis guessed that the lad's definition of benevolent was different to his.

"Did you think that was unfair?"

The boy look several seconds to answer, his freckled face twisting as it echoed the battle going on in his mind. Eventually, he decided on discretion rather than continued defiance.

"No master, it was fair. I'm sorry."

"Good. Now come, sit with me in yon arbour." Loomis said, gesturing towards a roughly cut wooden bench nestling in under a sheltering willow tree. Master and apprentice both sat down. Loomis wondered why he was bothering letting this fidgety, undisciplined, unnamed apprentice take up his valuable time. Not that he was exactly what you might call busy. Alone among the Elders of Wrangwysh Toft, he did not have to spend part of his time teaching. He was a peripatetic, in theory anyway. More often he was just ignored by the apprentices. Which suited him. On an impulse he handed his pollen broom to the lad, whose eyes formed amazed saucers almost as wide as his gaping mouth.

"Hold onto this for a minute," he said gently.

"I'll be careful Master," the boy said in a hushed tone. Loomis noticed that he had stopped fidgeting, so concerned was he with his burden. The broom was actually pretty durable. Loomis had used it for several decades without getting as much as a scratch on the iron-hard ebony of its ten-foot-long shaft, nor causing any damage to its subtle gears and mechanisms. Nevertheless, it was very unusual for an apprentice to be trusted to hold a broom. So unusual, in fact, that at least half of Mistress Melrig's class was now paying more attention to what was going on in the arbour than to their increasingly testy teacher. She hadn't noticed the reason for her charge's increasing inattention, and was dashing, as best a dumpy, not-very-young woman could, around the group, shouting and slapping at heads.

Loomis ignored the increasing mayhem. It was amusing, very amusing actually, but he had a job to do. He held his left hand out in front of his face, palm down and with his index finger raised six inches above his hand. After a few seconds a black-and-orange butterfly alighted on his elevated finger. He presented his right palm to the insect. His fingers ran quickly though a complex series of shapes that were argumented by the bright colours tattooed on his palm. The butterfly froze. Loomis turned to the boy.

"Species?" He asked.

"That's a viceroy," the boy replied confidently, "Basilarchia archippus."

Loomis wrinkled his brow. "Are you sure? Looks like a monarch to me."

"Of course its isn't! Look, there's a black streak on its hind wing. Crosses from top to bottom. Monarchs don't have one."

"Well, yes. But that was an easy one. How's your nose?"

The boy shrugged. Loomis thought that was a sensible answer. Olfactory skills were the hardest to acquire, and among the most important. No apprentice with a grain of sense would boast about his or her nasal skills. It was way too easy to come unstuck. Loomis decided it was worth a test. With great delicacy and precision, he ran his little finger down the paralysed butterfly's abdomen. It came away carrying the merest trace of pollen, bound by a tiny amount of nectar. He sniffed it, then held his finger out. The lad leaned forward and inhaled deeply. His forehead tightened in concentration and his nasal pouches ballooned up as he sniffed deep and long.

Without intending to, Loomis found himself examining the boy's eyes for traces of red, his nose for signs of irritation. Every year it seemed that more apprentices were lost to the pollen allergy, like the bright-eyed boy who had been the joy of his life.

"A lantana of some sort, Master, I think."

Loomis smiled. The arbour was dotted with the flamboyant red and yellow spiked flowers. "Which one? Purple or orange?"

The boy sniffed again. "Orange?"

"Good guess, but wrong. Purple."

"How do you know that? They always smell the same to me."

"Me too." Loomis took a span to enjoy the mixture of surprise and bafflement playing out on the boy's face. He held his finger up. "Look. The pollen of the purple variety is slightly more yellow-red than that of the orange. Of course, if you had been attending to Mistress Melrig's botany lessons you might have know that already."

The boy looked suitably chastened. Loomis couldn't help but break into a smile, then a thin peal of laughter. The boy joined, in and soon most of the botany class were looking in puzzlement at them. Mistress Melrig had finally noticed the source of the disturbance, and was standing with hands on her ample hips, gazing balefully and wagging a finger at Loomis. He waved back cheerily. With a flick of her severely cut, straight black hair, she began to march towards him. Her class trailed eagerly after her.

"Oh no." Loomis groaned. But he was spared a showdown with Mistress Melrig. She had barely taken ten paces when the sound of a great gong echoed down the hourducts. Everyone froze in surprise. There was at least a thirdhour until the next scheduled sending, and they were not usually announced so clamourously. Clearly something was up.

With a circular motion of his talking hand Loomis dismissed the transfixed butterfly. Then he stood up and, after retrieving his pollen broom, headed for the balustrade.

Knotting his courage, he peered over the edge. On a roadway below a clump of startled hour criers were scurrying towards the nearest hourduct. Their black and white coats trailed long scarves, which twisted in the draught of their breakneck passage. The last one in line tripped over a trailing scarf, and tumbled headlong, much to the amusement of the watching gaggle of apprentices. He was quickly on his feet and chasing after his fellows while rubbing a bruised head. By the time the criers reached the hourduct, their minions were arriving and beginning the slow, difficult process of organising themselves. Fifty undercriers formed the van. Behind each of them snaked a line of a twenty-five under-undercriers. Milling around behind them like competitors in a mad relay race were thousands of under-under-undercriers.

Loomis shook his head in mock dismay. The news criers were never the best-regulated guild, and this urgent summons had wrought entertaining havoc among them.

"Master?"

"Yes, boy, what is it now?"

"Master, is it true that once the news passed through the Great Redoubt on the wings of the Earth Current? And there was no need for the criers, for all of humanity's uncounted billions could read it themselves."

"What an absurd notion!" Mistress Melrig snapped. "What on the black Earth have you been putting into the lad's empty head?"

Loomis shrugged. "Nothing I said." He felt an urgent need to change the subject. "Look now, the hour slip has arrived."

The chief news crier, a bony etiolated man called Redeheid, emerged from the hourduct clutching a sheet of yellow paper. His immediate underlings clustered close to him, their pens scribbling furiously as he recited the text to them. As soon as the cry was done, the criers spread out. In seconds they were surrounded by constellations of undercriers. The next order of magnitude of pens descended to paper. When they had the bulletin down they sprinted headlong away from the melee, each desperately seeking room for their own tiny solar systems of under-undercriers. Once again papers were inscribed, hopefully with the accuracy and precision that was the otherwise dubious guild's proudest boast. Then, the lowest echelon of the criers' guild spread out in the four canonical directions, and all points in between.

Loomis leaned back on the balustrade. Before long an under-undercrier came scurrying past. The Lepidopterist's arm blurred out and snatched the paper from the man's hand. The under-undercrier stamped his foot and his face reddened with indignation, but there was little he could do to challenge someone of Loomis' high ranking. The lepidopterist carefully read the hour slip then returned it to the infuriated man, who promptly fled.

Mistress Melrig snorted at his departing back. "He might have at least told us what the substance of the hour slip was." She turned towards Loomis. "Well?"

Loomis took up his lecturing pose, chin up, hands grasping his robe's collar.

"There is to be an Exhalation."

A babble of excited apprentices' voices rose at this news. The last Exhalation had been three hundred and fifty six years ago, and there wasn't expected to be another one for at least a hundred years. It would be like ten years' worth of the festival for the raising of the Wall of Safety, all rolled into one ecstatic day. And it would be a lot of work. A devil of a lot of work, Loomis thought, gloomily.

"When?" Mistress Melrig asked, pointedly.

"Five years from this day."

"You jest."

"No. Five years."

Sarcasm dripped from Mistress Melrig's lips. "By the Days of Light, our guild barely numbers five million. How can we be expected to raise an Exhalation in five years? And why? Have the Watchers been dismissed? Has the sun re-lit? Has Loomis found honest work?"

Loomis shrugged. He was stunned by the prospect. A mere five years — it was impossible. They would have to raise as many apprentices a possible, as soon as possible — aye, and recruit millions of labourers. Then there was the co-ordination with thousands of other guild houses on hundreds of echelons and through the Great Pyramid. His head swam.

"So," Mistress Melrig insisted. "What's the big news?"

"There is to be a new Master Monstruwacan," he said simply.

Everyone's head turned upwards, as though, by dint of stunned curiosity, they could peer through the hundreds of echelons above, past the actinic detonation of the Earth Current-driven generators, onward through the thirteen hundred and twenty floors of the pyramid, to the Tower of Observation at the apex. Silence fell over apprentices and elders. There had not been a new Master Monstruwacan for time out of mind, at least the mind of the lesser mortals of the Great Redoubt. The more senior Monstruwacans would know, but they rarely descended below the surface. Except for Exhalations.

Loomis' heart leapt with hope. He would ask one of them. They surely would know what had happened to his son.

All he had to do was wait five years. Then he would have his chance.

Five years passed like the wind rustling through the lungs of the Great Redoubt. The Guild of Lepidopterists grew to seven million strong, but still remained one of the smallest of the underground guilds. Five years of endless labour, convoluted planning and desperate racing against time. It was impossible to guess how many caterpillars were raised, pupated and frozen to wait for the great day. But in the first two years, the effort came close to ruining the Great Redoubt's fecund farmlands. Caterpillars were everywhere. On the fifty-seventh echelon every plant was gnawed down to a nub. Even where they were under more control, everything seemed to be covered with twitching, gliding blobs of colour, forever seeking their first and last meal. Special precautions had to be taken to protect infants from suffocation, or poisoning by the many lethal varieties infesting the underlands.

Eventually, and to the great humiliation of the Lepidopterists' Guild, the Monstruwacan Council decreed a six-month hiatus to get the situation under control. Amid ridicule from the other guilds, the Lepidopterists regained their poise. The next great hatching was much better controlled, and the Monstruwacan Council again smiled on the butterfly farmers.

And so it went on, until hundreds of billions (some said upwards of a trillion) of pupae were stored in vast, cooled galleries on each of the Underground Country's three hundred and six echelons. A year before the Exhalation, the Guild of Windmasters spread throughout the Great Redoubt, mapping the subtleties of wind flow through both Underground Country and the Great Redoubt. Loomis was far from being the only greybeard who noted quietly that the two halves of the Great Redoubt, despite the claims of legend, did share the same set of lungs.

Finally, the great day dawned. As one of the elders of his guild, Loomis was offered the chance of watching the Exhalation from the lowest tier. The offer was tempting; it was decades since he had stood amid the three hundred and six fields. There would be unbounded opulence on the lowest tier, the fields would be flowing with food and drink and garlanded with millions of flowers, their scent as intoxicating as vintage Goldale wine. It would also be the best place to see the display; fully a half of the butterflies would be released from the lowest tier. But Loomis had chosen to stay in his home, its two hundred and fifteen fields seeming more comfortable. He also felt that he had a better chance to meet a Monstruwacan up there.

Loomis was one of the first people on his echelon to feel the Exhalation beginning. He was standing on an ornate spiral stairway, midway up the North curve of the outer wall. Through his bare feet, he felt a subtle change in the normal vibrational timbre of the Redoubt's naked metal. The spectators chattering excitedly around him were unaware of the change at first, but then the amplitude began to mount. At first, there was only a single, pure tone, like a million voices in wordless, joyful unison. Then understated overtones manifested as harmonic variations on the ecstatic main theme. Loomis glanced towards the roof of the echelon. Six dozen great silk flags, each handled by a hundred hauliers, waited for the call to action. Loomis felt a pang of worry. He put it aside — whatever happened, his work was done.

He looked down at the millions milling around below. They were clad in colourful garb, and garlanded with bright flowers. They were a happy chaos of colour and joy, but Loomis was looking for something else. He opened his mind, then waited. As the butterfly armadas raced upwards, gentle breezes began to play through the echelon. From every metal branch and bronchus and bronchiole of the underground country's lungs, from every hour tube, and from every balloon highway, soft, sweet-scented zephyrs played. His mind continued its search.

Then, someone touched Loomis' mind, with a clarity that made even his weak mental voice sing in harmony. He started to descend the stair, searching for the Monstruwacan.

As Loomis reached the floor level of the echelon, the first butterflies erupted from the mile-wide central light well. They were too far away for him to distinguish individual insects, but he knew that the almost solid-looking column of flashing green, white, and black was made up from uncountable four- and five-barred swallowtails. It had been deemed fitting that the first defiant challenge to the Night should come from the Aristeus named, as they were, for an ancient, long dead sun god.

The column rose with majestic slowness, its homogeneity defying the chaotic flight patterns of its myriad members. High above, the great silk flags unfurled. As they measured their several-hundred-yard lengths, butterflies rose from ten thousand cages. Close by Loomis, legions of Birdwings, Pine Whites, and Pelidne Sulphurs formed arpeggios to the great chord ascending the central light well. All around the echelon, innumerable minuscule specks of the Master Word were freed to ascend the lesser light wells. Their passing created a coruscation of winds, tousling the spectators' hair and whipping at the clothing. Ill-secured hats and scarves were grasped and thrown upwards, never to return. Their former owners cheered their losses until they were hoarse.

His professional pride satisfied, Loomis sought the Monstruwacan. He found him standing a few dozen yards to the North. He was an imposing figure: fully a head taller than the tallest normal man, and exuding an almost palpable air of authority. Despite the crush, there was a little empty zone around him, emphasizing how reluctant people were to approach him.

Loomis' mouth suddenly felt dry and his tongue tried to stick to his the roof of his mouth. He took a deep breath and stepped forward.

"Master," he said respectfully. "I would crave a word with you."

The Monstruwacan tilted his head and looked down on him. To Loomis, it seemed that a searchlight had been turned on his soul. He had met Monstruwacans before, but this one had a power and clarity rare even among his caste.

"Ah, a Lepidopterist. How may I help you, child?"

"It is of a child I ask, Master," Loomis said carefully. "My child. A boy rejected by my guild when he was cursed by the allergy sickness and since lost to me."

The Monstruwacan spread his hands. "Why would I know of this boy? Surely when he left your guild another took him in."

"No, Master. He rejected the blandishments of the other guilds, claiming to want to seek his destiny in the Great Pyramid … and perhaps beyond."

"Beyond? That is unlikely, it is very rare for — " He paused, as if recalling a long-forgotten memory, then considered the Lepidopterist carefully. "Is your name Loomis?"

"Yes, Master! How did you know?"

The Monstruwacan's brow furrowed and he contemplated the great ritual in silence for several minutes. Loomis, caught in a fever of hope and fear, dared not speak, lest he cause some fatal upset. In the rafters of the echelon, the last of the upsurging armies of butterflies were rising out of sight, disappearing through the many holes in the roof. Many would continue to climb the light wells, accruing new celebrants as they ascended the remaining two hundred and fourteen echelons of the Underground Country. Fifty echelons below the lowest floor of the pyramid, cunning nuances of light and scent would thin the relentlessly ascending butterfly nations by guiding many into long, Mobius-looped corridors, or tightly wound passages describing logarithmic spirals, where they would wait their turn. After the majestic central column of life had passed from Humanity's Underground Kingdom into the Great Pyramid, the waiting myriads would be gradually released to continue their journey.

"There was one," the Monstruwacan said eventually. "A boy bearing the signs of your calling on his face. He begged to be allowed to study for our guild. We refused. He was too old and it was unprecedented for someone from the Underground Country to seek such a boon. We encouraged him to return home and seek happiness among his people. He refused and defiantly set out to visit each of the thousand cities. For ten years, he wandered the Great Pyramid, staying a week in one city, a few hours in another. In due course, his peregrination was done, and he stood outside the Great Observatory at the apex of our world.

"His persistence greatly impressed the Council of Monstruwacans. You should be proud."

A lump grew in Loomis' throat, and tears pricked at the corners of his eyes.

"We expected him to ask again for admittance. We sought soft words to mitigate his disappointment. However, he surprised us again. He asked permission to brave the Land."

Loomis felt his heart lurch.

The Monstruwacan's face creased in sympathy. "He was of age. We had no grounds to deny his petition. Six weeks later your son — who was given the name Brere for his stout heart — set out in a party of forty-three brave, foolish young men. Millions watched as they crossed the Grey Downs without incident, skirted the Dark Palace, then fought valiantly in crossing the Road Where the Silent Ones walk."

Loomis felt a wave of peace encompass him. The Monstruwacan continued: "Then, as they approached the three Silver Fire Holes, a wave of blackness swept from the Thing that Nods and engulfed them. When it had passed, no trace of our valiant explorers was left behind."

An hour later, a group of sweepers found Loomis. He was kneeling in peaceful supplication, his face crusted with old tears. All around him were the bodies of millions of dead butterflies, the sad, inevitable fraction of the Exhalation that had failed to achieve their destiny. Their broken, exhausted bodies were continuing to filter down, and were already two hand spans deep around the Lepidopterist.

High above, legions of butterflies swept through the thousand cities, then burst out of the twelve hundred thousand embrasures of the Great Pyramid in a detonation of colour and motion. Actinic beams kindled by the Earth Current and guided by cunning prisms and mirrors illuminated the circling flocks.

The four hulking Watchers quailed, if only briefly, at humanity's defiant exultation. The insects swept around the pyramid in ever-widening circles. After a little under an hour they began, slowly, to die.

Night returned to the Earth.

© 2001 by Nigel Atkinson.

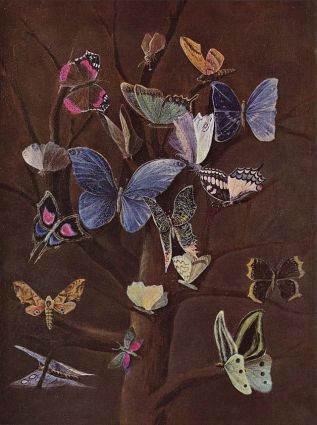

Butterfly painting by Wilhelm von Kaulbach, c. 1860.