Imago (Part 1)

by

Brett Davidson

In the declining hours of a certain day, Ael leaned over the balcony of her home and savoured the evening glow which was like a sunset, but not a sunset. Her history teacher had told her of sunsets, but such things didn’t happen in the Underground Fields and there had been no sun at all in the Night Land above for millions of years. Nonetheless, in the clock-created mornings and evenings leading up to the coming Exhalation, when the population of butterflies was being built up step by step, she often saw great clouds of shimmering crimson and gold wreathing the enormous hanging lanterns as they proceeded on their way along their ceiling tracks.

Her hands tightened about the rail as she was overcome for a moment by a feeling that was one part vertigo, one part claustrophobia and one part some nameless longing. She thought about those butterflies: they bore no resemblence to their larval stage, yet within the larva there was encoded the complete and inexorable directive of metamorphosis that lead to these shining creatures. How strange to be two lives, separated by a threshold of disintegration and renewal when human beings had but one, rounded as it were with death.

She looked down, and the world turned. She might have fallen, and toyed with the idea of leaping, because the spurt of fear that came with the almost-intention was a delicious thrill.

Because things must be balanced, she looked up and saw the criss-crossed ribs and vaults of the artificial sky. On the edge of sleep she often tried to imagine that roof of stone and the great metal mass of the Redoubt above her splitting open to reveal the free and empty sky. She imagined many things in fact; not only sunsets, but also islands and seas. She had never seen a sea, but lived in a village that climbed a stone-grey tree like metallic ivy. In the manner of most villages in the Fields, it was a cantilevered spiral that wound around one of the massive piers that supported the ceiling of her home cavern. The piers themselves, four hundred yards tall, were in an aperiodic arrangement which was supposed to give some sense of variation and surprise so that the structured scale of the cavern did not become oppressive, though it had that effect nonetheless. The accretions of ages had given individuality to the parts, but as the Eugenicists always seemed to be roving in search of genetic peculiarities to trim, so the Architects pruned their huge trees of stone and metal and consequently the lives of the people who lived within them.

The nearest lantern went into eclipse behind a pier and she retired indoors. “Genes, architecture and destiny,” she murmured bitterly to herself. “If only something other than death might alter me.” She did not fully understand it yet, but she had a very peculiar talent that could indeed change her as the butterflies were changed: she was a liar.

The lift ascended the central axis of the Great Redoubt at an interminable pace. Larger than a house, it had carried the class vertical miles from their home cavern and there were miles yet to go. Above the datum plane of the surface, the Pyramid and Observatory Tower of the Great Redoubt rose to a height of eight miles with over thirteen hundred cities layered within it like the pages of a book, while below there were a hundred miles more of subterranean Fields. Ael’s home was halfway below and her destination halfway above.

From time to time the Stress Master engineers stopped the lift at an airlock station and the attendant nurses on board checked the girls for signs of pressure sickness. For the periods of confinement as the atmosphere was carefully adjusted and the passengers were allowed to acclimatise, the lift car was equipped with entertainments, sleeping alcoves and facilities for ablutions, all of which were much used as boredom and vertigo took their toll. Ael herself spent much of the time sitting and reading the venerable poems of Aesworpth.

The Exhalation of Butterflies had been in preparation for years and more and more resources were being poured into the breeding of vast flights of insects to be released all at once. As a consequence, the children and adolescents of the Underground Fields were both the subjects of neglect and a nuisance and to mitigate this dual condition, they were sent on trips to various parts of the Great Redoubt that they might not otherwise have seen. On this trip, her class would be billeted in one of the middle cities of the pyramid and be taken on to see Watchmen who patrolled Outside and then an aerodrome that opened on to one of the external balconies.

Ael was not impressed, and unlikely to be. She knew all about the supposed purpose of the Exhalation already: her father was one of the respected lepidopterists of her level, he was training his son to succeed him and she raised hawkmoths herself as a hobby. She had also seen plenty of dead insects pinned in display cases and supposed that the sight of an inactive flying machine could only be as uninspiring as those dead butterflies. It was not as if she would be allowed to stand on the balcony of an aerodrome while one swooped and soared Outside, let alone be carried in one herself.

What she wanted most of all to sit in the Tower of Observation and what she wanted even more than most of all was to walk out of the Great Gate into the Night Land itself where she could have grand adventures and become a hero, just like the Watchmen and Aviators she read about. Right now though, she was sitting and waiting for neither of these things and she hated it. She looked around at her companions and one of them, her friend Feste, pulled a face at her. She ignored her.

Finally the lift shuddered to its last stop and the girls were ushered out. Sister Maia, the leader of the party, gave an earnest speech about the importance of good behaviour and not running wild simply because they were away from their familiar surroundings and neighbours, though those that weren’t completely disoriented were more concerned that they might seem gauche and ignorant. Then they were shown to their billets by worthy citizens of the city.

As it happened, Ael and Feste shared a room and as she tossed in her unfamiliar bed in a seemingly hopeless attempt to capture sleep, she saw her looking back, an expression of gleeful anticipation on her face.

“Think of who we’re to see!” Feste whispered. “Watchmen, Aviators!”

“Monstruwacans and Seers,” added Ael a lttle snobbishly.

Feste blew a raspberry. “What do they do but watch the Watchers, who watch them in turn?” she asked.

“Watch and see and watch and see!” Ael said in return and the two giggled over word games for a while. “See and do, see and be!”

On the first full day, the class visited one of the Halls of Honour with its army of statues and then they saw a Watch house and observed the Watchmen drill in a spacious hall with their flashing diskoi. The men were indeed impressive: tall and with an icy precision about them and smelling of sweat, oil and ozone. Several of the other girls surreptitiously took slip names from the laughing brutes and a few were even foolish enough to raise their veils and leave cards with their own slip node addresses.

The Watchmen’s helms presented blank planes and slots at first, and when raised, it seemed to Ael that the faces beneath were but growths shaped by the metal. They all seemed dull as statues to her and she haughtily kept her veil over her face.

The aerodrome was at once a stranger and a more familiar place. Living halfway up a pier with a father and a brother who bred butterflies for a living, the concept of flight struck more of a resonance with her. There was a strange combined feeling of the familiar and the extraordinary in the fact that she understood flight in the context of the enclosed Fields and stood beside the machines that would fly in the open space of the Night Land. She stared at the huge doors of the launching catapults and tried to imagine them opening as an airship carried her though and out and away.

The airships were beautiful things, made of brightly painted resinous silk stretched over extravagantly looped frames of alloy and composites, which Sister Maia described as “a brilliant concerto of tensile structure.” Ael just admired the shapes without considering how or why, though she guessed that she should when Maia continued, this time talking about “form following function” and “the intersection of truth and beauty,” which seemed to be the sort of language someone with poetic ambitions like herself should use.

She held her hand up to the clear nose of one airship which flowed back in sweeping planes to blend with the underhung fuselage and high shoulders of the delta wing. The belly of the fuselage itself seemed to suggest in one long and gentle sinoid curve both the dynamics of flight and the flank of a human body as it tapered towards the forked tail fins. Inside that mechanical body, Maia was explaining, coils of power cells charged from the Earth Current drove scimitar-bladed contraprops that spun on rings around the fuselages between the wings and tails. Each of the blades, Ael noticed, was painted a different bright colour; this was probably meant as a warning to keep the hangar crews away when the engines were powered up, but she saw it as a gesture of joyful defiance against the outer darkness. With their wings raised and arched just so, their glittering heads, extravagantly painted props and their delicate legs, the airships looked like a species of beautiful monster, and nothing like dead, pinned butterflies after all. She was told that the manufactories of the Redoubt were quite capable of making larger and more formidable wasp-machines but the Aviators, with their own heroic ethos like the Watchmen, refused to fly such things. This she understood perfectly.

The Aviators were scarcely less remarkable than the machines. Indeed they seemed to be the one half of a peculiar dimorphic species mated with the airships that only by coincidence roosted in the tiers of the Great Redoubt alongside human beings. Everything about them was light and colourful, like the butterflies that her family bred. Their costumes were of the finest silks, brightly embroidered and badged and thickly quilted for warmth in the cold air of Outside. Their armour was a lighter version of the set used by Watchmen in case they crashed and had to make their way back home on foot; their helmets were sculpted like the heads of insects and even the diskoi that they carried were more refined. Everything about them spoke, sang of a poise and intelligence that far outshone the blunt massiveness of the soldiers, or so it seemed to her. They had glamour — and one was the most glamorous of all.

Ael couldn’t stop watching this one very special Aviator who had an airship painted like one of her hawkmoths and wore a rakish motley. He didn’t swagger or brag and he spoke little, but everything he did or said had a greater value because of this. The exact opposite of the bulky Watchmen, he had an overall slenderness and slightness of stature that was unusual even among the lean Aviators. Overall, this gave him an odd, almost sexless appearance, but she forgave him for his grace and the affinity of insects that made him both more like her and so thrillingly different. His attractiveness was something that seemed to come close and then lead her away. This man flew, and maybe he would take her with him.

Of course she knew that this was a fantasy, but unlike many who were prone to fantasies, they were almost good enough in themselves rather than being a deception. Well, almost, she admitted. Then again, one might come true.

Feste, who had been watching nearby, gave her a pinch. “You are wake-dreaming, Ael — and I know of what you dream of too,” she teased.

“Oh, of what?”

“Oh, you know. Go on: dare,” she said smirking.

“Dare what?”

Feste laughed. “I know, I know! How can you not dare now?” She danced away, at least having the decency to leave her the space to make her approach to the Aviator on her own.

Ael turned around and saw the man watching her. He may have been just out of earshot and perhaps would not have made much sense of their dialect in any case, but nonetheless her face burned with embarrassment. She could run away now, but she would have to face Feste’s taunts if she did.

Very well, Ael decided. I’ll talk, and be just like one of the others. She walked up to him. “Hail,” she said.

“Ah, one from the Low Fields?” he asked. “Who are you?” None of the Aviators were old, but his voice was very young.

“A poet,” she replied. Of course it was an exaggeration and she had only shown her poems to her friends, but she had to appear to be something other than just another rustic devotee of the Aviators.

“Is that who you are or what you do?” he asked, thankfully not put off at all, though he was obviously rather sceptical.

“I ask this of each thing: ‘What is your nature?’” she countered, taking up his challenge and immediately thinking that she’d overplayed.

“This thing might not answer.” He said smiling, to her relief. She liked his voice, she decided, it was sweet — and he had decided to play a game with her..

“Then neither will I,” she said. “Tell me of flight instead. Tell me of your airship.”

So he did, and as she listened and watched him, she tried to speak like a sophisticated dweller of the high pyramid, rather than a rustic who constantly repeated and rhymed. He at least found her attempts amusing. His eyes glittered like obsidian. One pupil was dilated more than the other, she noticed, which was odd.

He demonstrated the controls of the airship, pointing out the function of the various dials and showing her how the manual levers in the cockpit made the wings twist and altered the pitch of the prop blades. She told him about her moths. He knew about moths, and had bought a few as pets in the past.

“Ah, you may have bought one of mine,” Ael said.

“Maybe I did.”

“Why do you fly?” she asked, thinking that since they had already unknowingly known each other as it were, he would also be a direct enactment of her own myths and motives.

“Because I couldn’t walk. I’ve always thought of the Great Redoubt as a giant half-buried in the earth, the Pyramid its head and helm and the Underground Fields its lungs and entrails. We are penned here by the Watchers and I wish that somehow this giant could free itself, stand shaking the clods of soil from its body and stride across the Land. In an airship I can stand as high as a Watcher and fly faster than anything that runs.”

She laughed. “Cap-dweller, you think that all sense is in this weighty top! Your Pyramid seals in something much lighter that wants to emerge and change. Can you see such, so-named Aviator?”

“Maybe I do now.”

Ael laughed again; even she saw this as clumsy, but it was an exception and mostly he was clever, light and witty. Silently she thanked Feste for her provocation and decided that she’d like to continue talking with him. Time was running short, though; the chaperones and Sisters would never violate a girl’s dignity by calling her name aloud in mixed company, but they were making it clear by their stances and raised voices that the visit was over its allotted time already and the group should be gathering together to move on urgently. Sister Maia was pointedly looking around, practically standing on tip toes as she counted heads.

Ael was not going to leave without also leaving some trace or link. She had to know the name of this Aviator and give him her own. She gave a sly grin to the Aviator and trotted up to Feste, tugged at her sleeve and demanded one of her cards.

“Oh-ho,” Feste chortled. “What are you saying now?”

“Ssh! Grant me a card, tell none!”

Feste’s smirk became wider. “If I don’t or if I do?”

“Do, or if you don’t I’ll...”

“You’ll what?”

“Grant me a card, Feste!”

She snickered and brought a card out from where it was concealed in her sleeve lining. “Done — and don’t forget your following favours, Ael.”

Ael snatched the card away before she could tease her more and quickly scribbled her own slipname over Feste’s. Looking around to see that the chaperones weren’t looking, she darted over to the hawkmoth airship, flicked the card through its open canopy with a wink at its bemused pilot and hurried back to the gathering class, but not before she was noticed.

“Ael of Salmakis,” hissed Maia in her ear. “You have been tardy!”

“My contrition, Respected Sister,” she said earnestly. “I was fascinated by the airships — such I liked and so I see that I will be an Engineer!”

The trip ended with an address by a tall elderly woman in purple, one of the ruling Monstruwacans, who told them of the sublime absurdity of the Exhalation. How essential it was, she said, that something so pointless and contrary to the rule of the Night Land be performed on such a grand scale. It was to show the Watchers, the Silent Ones and entropy itself that the warmth of the vanished sun still endured in the heart of the Great Redoubt. The honour of this speech was supposed to be the highlight of the trip, but as far as Ael was concerned, everything significant that was going to happen had already happened.

Returning home to the depths of the home Fields, she found her father, as ever, inspecting his latest batch of butterfly pupae. “Morpho rhetenor,” he said proudly. “Seven inch span. Iridescent blue. Lovely.”

“More butterflies for the Exhalation?” she asked without interest. It was almost to spite him that she kept her moths.

He smirked. “Some, but only some. These are far too valuable. Because so many are going Out, there’s a premium on this breed now. I’ll make a nice profit on these selling them as pets to society ladies in the upper cities.”

“Good for you.”

“Good for us, dear.”

“So say.” She went to her room to wait for a message from the fascinating Aviator.

There was no message from the Aviator that day, nor the next and on the day after that, Ael was sick. She sat in bed, wrapped tightly in her quilt and looked out of her window to watch the hanging suns go about their peregrinations. She was old enough to know that such crushes were irrational self-deceit, but she didn’t know if anyone was ever old enough not to suffer in this way.

Listlessly, she checked the boxes of soil where a batch of hawkmoths were pupating, but they showed no sign of emerging yet.

A day later she was at school, pleading that she had succumbed to a delayed effect of the pressure changes, which was believed. As an added boon, she was excused for a while from physical culture and drill classes, in which to her shame she had never excelled.

There were other girls who had fallen ill, but returned to school with knowing, possessive smiles and full of sly chatter about the messages that they’d received from the Watchmen and Aviators. They recited litanies of their names: Tires, Ashelden, Russ, Orlan, Angeleve and so forth. Ael suspected that most of these names were made up, but her spiteful accusation of one girl only left her the loser in a scuffle.

Finally, when she was at home cursing her own stupidity in both failing to learn the Aviator’s slipname herself and in ever having seen him in the first place, her table chimed. She rushed to access her homenode and found the critical, vital message there. She at last had a name too: Sartor, of clan Phaenes. The message read: “?”

The civilisation of the Redoubt was constrained more by custom and meme than it was by force. “We’re here because we’re here,” as a tautological drinking song had it, with the chorus, “I am who I am!” While Ael was of the Underground Country and most likely destined to remain there, this was largely so because this assumption was not questioned. Likewise, while she was chaperoned when in strange districts, she was not watched in places where she was expected to be as it was assumed that she was already mindful of everyone’s eyes. Therefore, she realised, it logically followed that if she was not accompanied, it would be thought that she was in her rightful place. Engineering and concealing an escape was technically simple: she informed the Sisters that she had suffered another attack of pressure sickness and absented herself from classes at a time when she knew that her father and her brother were on an inspection tour of the butterfly hatcheries. Everyone assumed that she was in bed and no one should be able to prove otherwise.

Of course while her strategies for escape were easy in theory, her most rigid guardian was herself and this waywardness was not easy at all. To rise even one level above her own without supervision induced reflexive agoraphobia and she would not have done so if she did not have one specific destination in mind that was as clear and real to her as her home. It was that goal, Sartor, that she defined as her foundation of identity and she even kept repeating his name to herself under her breath as a reassurance: “Sartor ex Phaenes, Sartor ex Phaenes, Sartor...”

The lift came to one of its halts with a bang and a hiss. She bit her lip behind her travelling veil and tried to act as if she had been on this trip a thousand times before. No one could hurt her, custom was her armour.

Sartor could hurt her. She was breaking custom with him as her classmates only dreamed to do. He could slip his dagger right into her heart through only a couple of layers of silk. A vulgar simile occurred to her and she felt queasy.

He met her in formal costume at the final stop, the silver moth clasp of his flight at his throat. She trembled with guilt, thinking that he was beautiful but that she had deceived herself and had to be lead away almost in a daze to a commercial billet for solitary women. Those who watched saw a man in uniform and a woman in a veil following all the forms of propriety.

“Why have you done this?” he asked when they had been alone for a while.

Ael was confused. Hadn’t he invited her, or had she suggested the invitation first? “Why have I, you?”

It was so strange, she never thought that it would be like this at all. When she had thought of adventure, and when she had planned this assignation, the fantasy of that adventure had been illuminated with the tension and thrill of secrecy and deceit. What she had not expected was the feeling that somehow something within her was tricking her into pretending that it was all so accidental. Almost every step had been planned, but it seemed as if she had taken every one of those steps on a random walk determined by the oracle of dice lightly tossed from her hand. Her secret self had loaded those dice, however, and this paradox made her dizzy.

“Why anyone?” she asked.

He shrugged. “Perhaps I am tired of being only myself.”

His manner seemed as casual as an imp of the perverse whispering temptations. “It is of no consequence, it is not true,” it seemed to say in the spaces between his words. “Earth has slipped into its final night and thus all is a dream. Let your fate fall where it will, because when you wake you will be someone else and it will not matter.”

“I had a dream last night,” she said. “I dreamt that I was a butterfly, and when I woke, I wondered if I was a butterfly dreaming that it was me.”

Sartor laughed. “I have read that story too — there is no need to lie to me!”

So she decided to trust him, on deceit, a chance and a coincidence.

“Take me flying,” she said.

“Maybe,” he told her.

© 2003 by Brett Davidson.

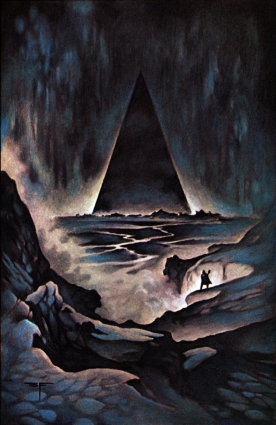

Image copyright by Stephen Fabian.