Meanwhile, She Dreams (Part 2)

by

Brett Davidson

To Meanwhile, She Dreams (Part 1)

That night she dreams of the Land.

The dream is lucid and she is detached, knowing that it is a dream, having thoughts about the dream. She thinks at first that it was inspired by the report that she read that day, but it contains imagery that she could not have imagined.

She sees first a hand, slender and feminine, which she knows is her own while also knowing that it is not. The hand grasps at some roots or vines to steady herself. She pulls herself to her feet and looks around. She is outside, in the Land somewhere.

All about her is darkness, but isolated sources of light here and there, living phosphorescence and natural vulcanism, give just enough illumination to paint a landscape for her. It is composed largely of horizontals, making a plain as flat as she supposed a sea bed might be. Hot winds come out of the overall cold carrying the stink of sulphur, which makes her throat raw and her eyes water. Much of her skin is exposed, her flimsy city clothes only rags now, and when she is not almost burned she shivers.

Above all, her hearing is alert, because the blended shadows of this world make one vast cloak of concealment through which sounds give the most urgent hints and clues. Volcanic vents hiss and fume, and somewhere something cries. There are pounding footsteps somewhere and she crouches down to conceal herself, but knows that it will not be by sight that she is found. She probably does not have much time left; she was lucky to have lasted this long.

She turns back and sees a different shade of darkness, a great metal pyramid. It is entirely unlit by its own energy, but delineated by the light of one of the eruptions behind it.

Is this the Last Redoubt? she wonders. Has it fallen? Is this a prophecy? No, she decides, it is not. Huge as it is, this is not nearly as vast as she knows the Last Redoubt to be.

She hears in her mind a whisper, but a true voice to her night-hearing nonetheless. One word she hears: "Mirdath," and it wakes her.

Another frustrated day passes. On her way home she walks through an older part of the library which is being renewed. Workers are laying new tiles on the floor in the customary style of the Archives.

The tiles are aperiodic and while patterns are seen to emerge at various scales, they are all incomplete and infinitely variable. This is a lesson, she is told, or a lesson has grown to explain this style, which may have simply begun as a caprice. It shows that simple forms can compel complexity, and that therefore while a Scholar will suppose that time runs in cycles and that all changes blur into one continuum, one can also be reassured that within this continuum there is a refuge for uniqueness and freedom.

There is a contrary interpretation, of course, and that is that all the variation at a distance blends into a warm autumnal unity. This is supposed to reassuring too.

There is another simpler story about the tiles: since the cities are all rigidly square, and roofs and floors and shelves are absolutely parallel, some ancient architect decided that a little skewing of the angles is a healthy thing.

Ilde smiles to herself, her eccentric mood persisting. Reading her own lesson from those tiles, she might be tempted to skew her records. But as every lesson leads to another, they remind her that perhaps ultimately, whatever individual freedom she steals, it will be lost in the greater field of variation. Is this the constancy of the Archives, then? Is it all variation without truth?

She visits Oughtred the horologist again. She cannot pretend that the meeting is an accident this time and it should attract attention and censure for any number of reasons, though the Magister Dean of the College Library is a gentle and understanding old man who would most likely offer a few suggestions about the necessity for a chaperone and the exercise of appropriate discretion. She is not sure if she wants their meetings to be frequent, but certainly the occasional meeting that she chooses to think of as casual seems to suit her needs for the time being. They are, she admits, a distraction from her fruitless doubts and questions.

They talk about matters that are more philosophical than professional, and he laughs at her jokes and she smiles at his. He is, it turns out, an enthusiast for debate as well as timekeeping, and they play board games of his own devising where allegorical pieces are moved about complicated boards to enact elaborate abstract arguments. This man is not an ignorant tradesman, but an elite artisan who has become good at his craft because he has understood why he must be good, and he takes an artist's pleasure in an exercise that has been well-resolved.

Their mutual activity pleases and stimulates her more than adequately after all. Perhaps then a chaperone would be appropriate? She smiles and decides that she will not engage one, at least not yet. She flirted with one sin and now she decides to indulge herself with another. The thought unfolds a question of consequence: is she using him for her amusement? She chews her lip, almost saying something.

The horologist has not yet learned to read her thoughts from her dial, but he knows that something complicated is turning within her and he shows his concern. She blushes and looks away, but she cannot help letting so many pieces of her thoughts slip out and she blurts out her request:

"Do you have a diskos, a real one? My mother would never take me to see the Militia shows. I've only seen pictures and statues and I want to see something real." Damn her face and tongue!

"It is not permitted," he tells her for the second time.

"I know that. I know also that you are not answering me," she insists, feeling nonetheless that it is grossly unfair of her to press the point. But it is too late for regrets.

Reluctantly he nods. "Follow me," he says, rising.

She should not do this, she thinks. There are so many stories about what happens to women who follow men into secret rooms. But she tells herself that the two of them are simply members of the guild working side by side, sworn to behave decently with one another. She senses has no cause to fear — at least she no cause to fear what she has been told to fear.

The workshop that he keeps behind the hall is small and not particularly tidy. Plans and components lie about in no order that she can discern, and the documents themselves, she sees, are merely scribbles, prompters for the memory rather than precise construction diagrams. He could be either a casual incompetent or a very conscientious man who has trained his own memory to invisibly permeate and encompass the contents of this shop as thoroughly as a vine. The latter is almost certainly the case, and she is sure that if someone were to tidy the place up, it would be then that he would be unable to find anything.

He offers a seat and turns to a particularly cluttered bench, brushing metal shavings aside so that they fall glittering to lie amongst the dust on the floor. He sees her looking downwards and misinterprets her expression. "Don't worry about that," he says. "It'll be swept up. They sweep up everything here."

"Of course," she agrees, knowing libraries and their dust well. Here, even dust is not waste but a resource to be cultivated. If it is not swept up today, it will be swept up in a year, and if it is not swept up in a year, it will be swept up nonetheless eventually and the metal shavings will be mined again one day from great hoppers of dust that has been collected from myriads of trivial sweepings. They will find their way into the foundries, melted and poured into ingots and then they may be milled and made into more clocks and diskoi a thousand years from now. Nothing is ever lost in a closed system.

He shifts a few tools and rags to reveal a long box. He picks it up and sits on a stool with the box across his knees. "Here," he says. It is as stained and scratched and as unremarkable as any of the tool boxes lying about, hardly portentous. "I made it for myself and nobody noticed that I took it when I left the Watch."

His black eyes look into hers and his pale, long-fingered hands lie across the lid like moths. Those are an artist's hands, she thinks, not a soldier's, unless a soldier is an artist.

"Will you open it?" she asks, knowing that he is still reluctant to do so and trying therefore to prise it open herself with a little gentle mockery.

"Oh," he says, as if he had forgotten. "Yes." He opens the latches and raises the lid

Inside, the diskos lies on a bed of velvet, curved and as placidly beautiful as a sleeping scorpion. It is over a yard long, two spans across its circular serrated blade. The light catches it and sparkles and she sees her own coral eyes reflected, making ornament unnecessary. She reaches forward into the box and touches the mirrored surface of the thing. It is cold and she withdraws as if shocked. One pale smudge of a fingerprint is left behind.

"I don't know if I dare," she says, laughing nervously.

"It's not heavy," he tells her. "It's not live; you won't harm yourself — or me."

This is not what she is thinking.

She reaches in again and grasps the handle, which is wrapped in narrow braided strips of black plastic. They are unworn: this weapon has never seen combat. She lifts it up and it is indeed surprisingly light. Standing and backing away to give herself some space, she lets it swing loosely at first like a pendulum and then raises it, trying to get a sense of its use and trying to imagine the ozone tang and flashing blue nimbus of a live blade. She does not know, despite the reports that she has read, exactly what she should imagine, and so she parodies herself, striking poses that she has seen in children's book illustrations.

It is his turn to laugh now. "Live, the spinning blade has a powerful gyroscopic effect, and has to be swung perpendicular to the axis of rotation; otherwise you will find it resisting you," he explains. "Rather than hacking, you weave it about yourself in a spiral or looping zigzag motion, and then you will find it an advantage. But you have to develop quite powerful arms and shoulders to be fully proficient in its use. Women generally don't have the necessary upper body strength, unfortunately."

She shrugs, concealing her disappointment, but suddenly imaginary after../images weave coloured helixes in her mind's eye as if she remembered the sight of combat after all. "Why aren't you still a Watchman?" she asks.

"I never was. By temperament I was a dancer, not a slicer. I was too much the artist, so I made rather than wielded diskoi."

"Why did you leave?"

He shrugs. "Is there any one reason for such decisions?"

"There often is one that stands above all the reasons for staying."

"Then I had too much imagination," he admits. "If I could not see the Land and live long enough to make sense of what I had seen, then I thought that I would see if I can know it by other means in a library. I'm no historian like you, so making clocks is the best that I can do."

Does he envy her? Ilde asks herself. She had never thought of that. "You are a good horologist, aren't you?" she says, suggesting praise that she doesn't know how to offer directly.

"I am, yes."

She nods. Her mother would approve of this man, she thinks; he is not a hero, but that is something she certainly will not say. "Do you have doubts, regrets?"

"Of course. Everyone has doubts."

No, not everyone has doubts.

"What are yours?" he asks.

She decides to trust him, though she presents her words as a joke. "Suppose someone mistook everything that they saw, or told a lie, or played a practical joke on me and gave me a children's tale. Suppose that a word that meant one thing to me meant its opposite years ago or a file had been corrupted? Suppose anyway that ultimately none of it has any cause or pattern at all and our libraries are all filled with nothing but pointless fantasy?"

He laughs. "Suppose indeed," he says. "Suppose that I had made a sprocket with the wrong number of teeth and that what the clocks called called a millennium was only a week!"

She laughs with him and then is quiet and chews her lip. Why does she swing to seriousness and then hide in her silly jokes? She feels awkward, flustered, and she wants to leave but will not. She often wishes that she could read the emanations of other minds with a useful discrimination, but now of all times, she wishes that she could read her own.

Suddenly, Oughtred is more serious again. "I have heard a rumour," he says.

"Oh yes?" she says guardedly. She feels the need to share confidences with him, but she also sworn to confidentiality on many things.

"I have heard... it's more of a legend... that the experiments that lead to the entry of the pneumavores and all the other things... that the catastrophe was not an opening of reality that let them into our world, but one that took us into theirs. Do you ask this question? Do you think of what that may imply?"

He sits back and she is silent herself, wondering about what he has just said. He has knowingly or unknowingly shown something of his own secret needs for confirmation to her, and they are no longer mere philosophical correspondents. The both of them want not truths as such, not bare, dry facts, but a truthfulness that is woven of honest and easy need that is simultaneously a bond of profound trust. Each has decided that the other is the window for their secrets and there has never been anything 'mere' about their relationship at all.

It is almost inconsequential that she has asked this question herself, come up against walls of secrecy and honestly does not know the answer.

He tells her that he wishes to make a clock that counts not from past to future, but sideways, to see how far the Redoubt has diverged from the line of its true history. It is almost a joke, but he has made plans and he shows them to her.

She finally excuses herself and hurries home, grateful that the customary veil hides her face from passers-by. A chaperone should be engaged immediately, she decides. If there is a bond, and there is a bond, it must be tempered and it must be trained to grow like a vine on a trellis like her Fey-tree, so that it may be fruitful rather than become a disorderly and choking weed.

This is what she wants, but she has been infected with her habit of secrecy. Suddenly, and she never thought that she would, she envies those who have had arranged marriages, where all has been open from the beginning. She catches herself at this point: the word marriage has caught in the delicate turnings of her thoughts and of course it slips from her mouth. She coughs to confuse anyone who might have overheard her.

In a dream that night she is in an airship, looking down on the Land. The vision is brief, but astonishing. Someone is with her, his arm around her, his hand resting in the soft curve that lies between ribs and pelvis. Below her the Land, so often described as parts and pathways, becomes a great pattern, just like a tiled floor, but more random, with no segments like any others at all, yet clear for reading and understanding as any map. It is like the view from one of the balconies that must have been in olden times launching stages for the airships.

She has an acute sense of vertigo because she moves and the view shifts. It is as if the Redoubt were toppling over, and she starts, and indeed she does fall: out of her bed and on to the floor.

She lies motionless for a moment, tangled in the sheets with one leg still awkwardly crooked up over the side of the bed. Only her cricket in its cage will have seen her, but she feels ridiculous, and carefully climbs back into bed. She tries to get back to sleep, not least to dream again, and perhaps see the face of the man who was with her.

Dreams compose themselves not only of happenings, but of knowledge also. In a dream, one is sure of many things that make their contents eminently sensible. In this dream she knows that she and the faceless man are lovers and she knows that it is some time in the distant past. Certainly it was in the very distant past because while the Lesser Redoubt fell a hundred thousand years ago, the last airship flew millennia before even that time.

She hopes, but she does not sleep.

What inspired this? Hangars still exist here and there about the perimeters of various cities, but their outer doors have been welded shut and reinforced and the spaces themselves converted to residential purposes or storage or made into gardens. Her own guild maintains a few as museums, and she has seen the plump delta of an almost intact airship that could have been readied for flight outside should the word come. But the word has not come, of course. She once inspected its cockpit and sat for a while in the pilot's seat, but the sight of the blind instruments staring back at her was too disappointing to be endured for long. She never visits these mechanical tombs now.

Despite what she knows and what she doesn't know, she feels that there is an essential link between the dreams that she has had, that there is something constant about who she is and who he might be. Is it just the fantasy of a lonely girl? It doesn't feel like a fantasy. It is in the nature of illusions that credulity is a part of the perception, as one of the essential maxims of the Scholars' guild has it, but she doesn't believe that in this case. She is sure that the dreams are real and that what she knows is true and she wants to know more.

She stares at the ceiling, hating it for her wakefulness, and lets her hands creep lower under the covers. This warms her for a while.

The next day in her free time, she lets herself be driven by impulse. As she wandered into the hall of clocks and learned new things, perhaps she will wander into another hall and add another unexpected dimension to her knowledge.

She imagines that her choice is random, but the hall where she finds herself is too significant for that charade. In the library adjoining the historical archives and reading halls, there are the offices that contain the records of bloodlines. The population of the Redoubt is vast, but it is also finite and over enough time, as there is always enough time, inbreeding is a risk. Therefore all matings are registered and checked for viability. She has seen more than one couple denied license because it was found that both bore the same gene for some fatal condition.

In the past, genetic engineering might have ameliorated their risk, and indeed in this time it does. But rather than making changes in one generation, the Eugenicists of the Redoubt conduct their work over centuries, guiding clans and bloodlines together and apart by subtle means; sponsoring some alliances, barring others, taxing and rewarding unions. It seems obscure as a lottery to some and she wonders whether the Eugenicists have the same doubts that she has and whether they too have some equivalent of the lessons of the tiles.

She makes herself busy and finds her own Clan Timarchos records. Her options are unlimited, she finds, though her mother has already told her this — or rather her mother had told her that her genetic options were unlimited, despite the peculiarity of her eyes, for what that was worth. Perhaps it is worth something now.

She puts a hand over her mouth as she smirks, thinking that she is being silly. The records of Clan Parzsal flicker across the view table under her fingertips almost by accident.

A few days later she is back in the horological hall.

Some of the instruments are artworks, Oughtred explains, their function lending itself easily to allegory, like his games. Peculiar automata waltz about in a few of the more whimsical specimens. She closely inspects one which at first looks like a scribble of overlapping and eccentric ring segments crossed with a chess board. It has human figures standing on the rings, like planets on the orreries, and they wear stylised costumes. One has a motley pattern not unlike the library's tiles, but more colourful, and another in is baggy white, ornamented with a tiny black cap and pom-poms. Judging by their tracks, they and others in the mechanism will dance about each other, emerging from hatches and concealing themselves singly or in pairs, seen and unseen by the others.

"This is one of my favourites," Oughtred says. Of course it is. It is just like one of his games. "It has a basic cycle of just a week, but each cycle varies slightly. These figures meet over and over again, but never in quite the same way. It is called the Harlequinade Clock, or the Dancers at the End of Time."

"Harlequin? Is that the name of the designer?"

"Nobody knows."

People carried by cycles, powerless in their compulsions. The thought is unbearable and suddenly she must flee this man. Behind her departing back he is frightened himself, because, of course, he desires too: and in her mind it makes a great, hollow sound.

In another dream, again the landscape moves beneath her, but it is seen from a lower perspective than that of the airship this time. She stands on a balcony that vibrates slightly under her feet. A man touches her arm and whispers in her ear. It is him again, she is sure. She drinks a chilled wine and gazes expectantly at a red glow on the horizon. Downwards, at the base of a great black cliff, she sees churning dust and a cracked paving of some sort that slowly slips underneath and appears to be consumed. She is a passenger in some mobile structure, some lesser redoubt that crawls along a road. Looking up again, the glow beckons and warms her just a little. Is there some immense eruption occurring there beyond the rim of her sight? Should they not avoid it?

Her mood is strange, one of longing and anxiety: not fear of this thing, but fear rather that she will never reach it. The wine is no consolation, though the touch and the voice might be. She feels the warmth of his breath on her cheek and they leave the balcony together and in the half-light she almost sees his face.

A quick and almost unnecessary survey in the library reveals the era of this dream. It is of a time when the sun still shone, albeit dimly, and the earth still turned, though slow as a century. The cities of the earth proceeded on tracks circumnavigating the globe to remain in eternal sunlight and the time was called, plainly, The Age When the Cities Went Westwards. That was over twelve million years ago.

Ilde rests her hand on her chin, thinking. Are these dreams memories of who I was in past ages? she asks herself. Are our souls reused over and over like the dust? Has the bloodline of humanity simply assimilated me as those Watchmen were absorbed by that beast? Do they dream within its veins now as I dream my life within the Redoubt?

The lesson of the clocks and the dancers and the blood and the dust is that time is cyclic, but what cycles are being measured? The clocks display the orbits of planets that must surely be imaginary now. She has been told and she tells herself that there is enough time for everything, because there has been already, but the cycles also lead forward along a road to where they will one day end. The earth current winds the Redoubt, but one day it will fail and her home will freeze or a Watcher will breach the wall and it will see them all within directly with its own eyes and its seeing will unwind the springs of their being.

She knows that she did not ever go to the horological hall simply to see some happy demonstration of the certainties of her life. Her secret self drove her there because it wanted her to be further tempted to doubt and to wonder. The clocks are too sad for her, too finite. They are too sad for the horologist too, so he tries to lose himself in his games, his ironies and his eccentric designs. The Masters of the guild should never have assigned a thoughtful man to that position.

The Magister of Assignments feeds more reports to her, inadvertently encouraging her ruminations. There are more sightings of the thicket creature, and the Monstruwacans begin to make requests of a highly specific nature. Has anything like this been seen before? Has something similar in certain precise characteristics been seen? If so, how was it dealt with? The orders are transparent: they are surely considering a hunt. Shortly there will follow equests for personnel records, and candidates will undergo assessment.

Of course, this thing is no Titan and a single limited discharge of the earth current might obliterate it. For that matter, it is speculated that even the Watchers might be wounded if they so chose, but the order is careful, not willing to overplay its hand or upset the balances of the Land. In the millions of years of the Redoubt's history they have seen too many unintended consequences, and the reports will be considered for a time yet before any final decision is made.

The interregnum gives her time and impulse to think. She visits the hall of clocks. Oughtred is in the process of dismantling one particularly complicated mechanism. His deadline is close and he has no time to spare, even for her, and his regret is plain. She does not in any case want to speak to him after all; she only wanted to be reminded of his face.

Returning to her post, she feels as if she is part of a huge calculating mill herself, a sentient pin unable to be anything other than a pin. Eventually she will be bent out of true and dropped into the dust to be replaced by another, better pin. The thought is so bathetic that she laughs out loud at herself, attracting surprised glances from her colleagues. She blushes and bows her head to the view table before her again, but thoughts continue to turn and click. The process is almost unconscious, a cascading wave of insights and decisions that are so absurd that she will not name them.

She wonders if she is going mad and gets up, paces a little, attracting curious looks and stranger thoughts again, but she ignores them. Finally she runs to the office of the Magister of Assignments who hears what she has to say and sends her home with orders to remain there until she is called, in the meantime speaking to no one. That last proviso is a relief, sparing her a further, more stressful, confrontation.

Safe within her clan compound, she plucks a grape from the vine, the kiss of her house, but she does not speak to even her mother. She rushes to her private quarters, where she finally achieves some calm playing with her cricket. Its mind is a minuscule pinprick, almost as light in its touch as its tiny clawed feet upon the skin of her wrist. The creature is blessedly incapable of questions, merely an animated jewel, like a clock. She compels it to sing for her, then puts it away in its cage and retires to bed.

A few days later an expected call comes and she returns to work. Her mother, distressed by her silence, waits before the gate of the compound, but Ilde still does not speak and raises her veil, hiding her tears. Whatever happens, dear Mother, she thinks to herself, you will lose me too, in one way or another; and I am sorry, but what can I do?

Arriving at the library, she is met immediately within the Initiate's Portal by the Magister of Assignments, and he leads her straight to a private room. The space is well furnished and venerable, the walls ornamented with portraits and closed cabinets of a deep, expensive gloss. In the centre of the room there is a deep rug and a semicircle of half a dozen chairs. A man sits in one of them, long, louche and elegant in rich, wine-purple clothing with delicate luminous embroidery. This is no uniform or formal robe, but she knows immediately that the man is a senior Monstruwacan.

He rises, smiling, and indicates that she should make herself comfortable. Awkwardly, she falls into one of the vacant chairs. The Magister takes another. While this room is no cell, there is no file to be opened and she is no prisoner, charm is the most insidious of tortures and the man knows this. She does not think for a moment that she will leave this room without something having deeply and permanently changed. Her face burns.

The Monstruwacan steeples his fingers, watching her beneath the blush. "Tell, me," he says, "why this request of yours has been necessary."

"Is it true, then?" she blurts.

"Is what true?" the Magister asks, disingenuously. The Monstruwacan silences him with a wave of his hand.

Slowly at first, she explains her suspicions, thinking of the cadet whose report she first read. Will this session also be pored over by some other junior Scholar? "The beast, the thing... you will hunt it?"

The man in purple nods. He does not blink, she notices. "That is a possibility that we are considering," he says.

"Why? Wouldn't you upset some balance in the Land?"

"That is also a possibility that we are considering."

"Why do you even think of doing such a thing? You never do this..." She stoops herself, realising that she is being far too forthright, despite the allowances that have been made.

"Your thoughts are congruent with our own. To kill this thing would be a vital act of mercy for the spirits of those that were once human."

She is silent, never having expected such an open admission.

"Now tell me why you have requested to be considered to recruitment for any possible expedition," he asks. "Do you simply want to see the Night Land with your own eyes? Do you wish to kill? Do you wish to die?"

Strange currents are induced in her thoughts. She thinks that this may be her own reaction, but it is possible that he is stirring her mind himself to see what will float to the surface.

She pleads, pointing out that aside from the Magister she has been the principle nexus of communication on the matter of the beast. The Magister nods reluctantly, admitting that this is the case. He is embarrassed in front of the Monstruwacan and does not want to be seen to have acted rashly. She admits that she has never learned the skill or built the physique to handle a live diskos, but as a de facto specialist on the creature, she might direct the Watchmen or be consulted by them in some way. In her nervousness she almost lets slip the fact that she has handled a diskos nonetheless.

The Monstruwacan shakes his head sadly. "It is not a matter of skill, or intelligence or knowledge," he says. "It is not even because you are a young woman. Survival in the Night Land depends on a thousand subtle skills of awareness that can only be acquired through long training and experience... and then we would have lost your true talent." He looks at her sympathetically. "You were chosen properly," he adds, with an offhand glance to the Magister, who is visibly relieved. "Your perceptions were accurate. Your compilations were thorough, elegant and even... imaginative. We will need your attention and insight yet."

So she is a perfect pin after all, Ilde thinks bitterly, but not truthfully.

There is a sense of unslaked curiosity about the man, but he is also cautious and patient. She is more than a simple component in the apparatus of the Archives, but he has not yet decided where he shall put her, so he will wait until he sees more.

"I endorse your current assignment," he finishes, trying to be kind, and she is ushered out of his presence.

The Magister radiates satisfaction with himself. Incredibly, it seems that he has taken the Monstruwacan at his word and assumes that the inquiry is concluded and the judgement final. But she knows that he caught none of the underlying discourse. Objectively, things have gone well. She will not be disciplined, and with this positive attention she may well be promoted to a position of oversight or permanent liaison when this matter is finally concluded. But it feels like a humiliation nonetheless. Why did she even suggest such an idiotic thing? Talent is one thing, but poor judgement is another.

Freed for the day, though still sworn to silence, she is standing in the Hall of Honour among statues which will never bear her heroic likeness. Does she love that man, Oughtred ex Parzsal?, she asks herself at the feet of the man in broken armour. Does she love simply the idea of that man? Why did she try to escape from him in this way?

She curses this persistent melancholia. "You are not he," she says, another spillage of thought. She looks around, unable to shake of the feeling that she is being watched, but thankfully she is alone.

The next day Ilde speaks to one of the sweepers in the library, a woman she knows is of a clan allied to her own and on reduced hours leading soon to retirement. She is a grandmother, surely knowledgable and forgiving and perhaps a little cynical in human affairs. "I wish to engage your services," she says. "My family is not wealthy, but we can pay nonetheless." The woman nods silently; this is not the first time she has taken such a commission and the two are a little familiar with each other in any case.

Ilde is pleased with herself, confident, and stumbles immediately. She finds herself confessing too much, as if the overfull cabinet of her soul has been unlocked and all its contents spill out. "I have secrets," she says. "I haven't told my mother...I, he...I think it will be something real, something of Mine Own..." and so on. The old woman still says nothing, but holds her, and with the pressure of her arms, she realises that she is shaking.

That night she dreams too vividly again of past times. Is it poor consolation? Does she wish that she was that woman outside the ruins of the Lesser Redoubt, does she prefer to die as the Monstruwacan suggested? For a moment she hates the choices given to her, as if there were no other alternatives, no subtleties, no possibility of interpretation. She may as well hate the air that she breathes.

Will she then, in future, interpret? Will she now tell the Monstruwacans of her dreams, and apply for admission to their order? Will she watch the Watchers from the Tower? Will she present Oughtred with a grape from her Fey-tree?

She might, she will.

Whatever happens, she realises, and it seems to be for the first time that she knows this, she has been a child, and now that cycle has ended and a new hour will begin for her.

No more will she try to read trite and too familiar lessons from the dust and the tiles. This is the moment in which she will begin to make her choices rather than letting her life run in its old, youthful circles.

Time is running down, but it is not yet run out, and her dreams run backwards, each memory still older than the last.

That night, she dreams that leaves now vine green dance like the library's autumn tiles, and bright molten light drips through the fingers shielding her eyes.

It burns her, but it is beautiful and she realises then that it is the sun.

© 2002 by Brett Davidson

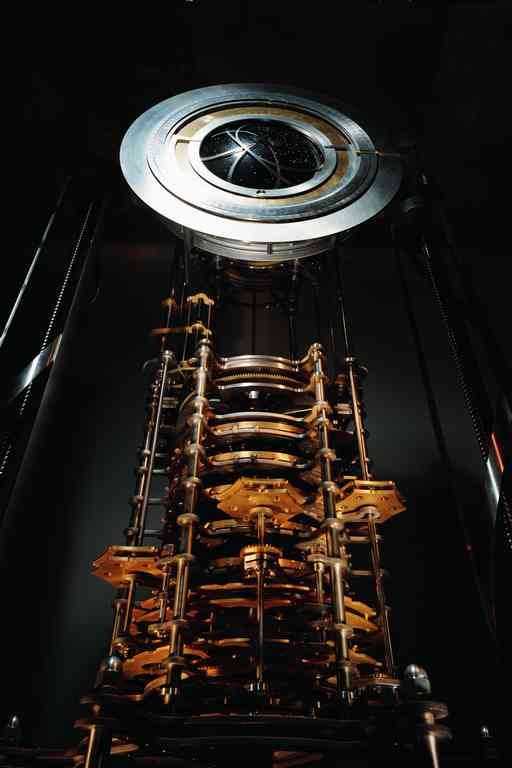

Image © by Rolfe Horne. Used courtesy of the Long Now Foundation.