A Mouse in the Walls of the Lesser Redoubt (Part 1)

by

Nigel Atkinson

I.

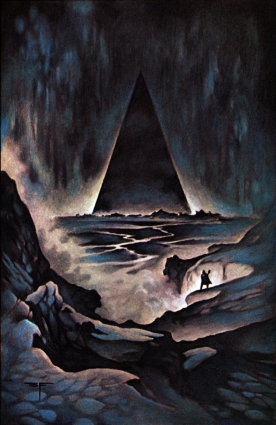

The Fixed Giants huddled under the glowing blue veil. Literally mountainous, their sluggish sentience rarely demanded movement. Sometimes, when the burning blue mist thinned, they would slump down a little. Days and millennia passed, but they never relaxed their scrutiny of the mile-high metal pyramid a hundred miles to the East.

On one otherwise unremarkable day, they watched as a flood of fire washed down the pyramid, incinerating a dozen beasts that had ventured too close and sending hundreds more fleeing for their lives. Before the liquid fire died away, a small door opened at the base of the pyramid, and a group of children stepped into the Night.

The children wept as armour-clad men stepped back inside the Lesser Redoubt. The last man in line hesitated, silhouetted in the splinter of light. He raised his Discos in a bleak salute; it flared for an instant, then he was gone. The dark returned, and a chattering, cacophony rose from its emboldened inhabitants. Beasts crawled, slithered and crashed among the sea of rubble that surrounded the pyramid. Most of the children cried and hugged each other. Alone among them, a young girl twisted a motley-coloured cloth in her hands, and waited patiently.

The pyramid stood at the top of a half-mile high hill. Three vertical beams of light marked its corners, and a ring of fused rock surrounded its base. This marked the limit of the ambitions of most of the creatures of the Night. Once in a while, a newly spawned beast, or one driven mad by frustration, would launch itself at the Redoubt. Infrequently, entire clans of beasts would attack the Redoubt, often using the bodies of their fallen kin to breach the Ring of Fire. At these times, malevolent liquid fireballs rolled down the pyramid’s sides with deadly accuracy, killing most of the attackers. The few that made it to the apex found the Prefects with their Diskoi spitting electric fire waiting for them. The defence had held for eight million years, and the defenders saw no reason to believe that it would ever fail.

At the Lesser Redoubt’s apex, two men watched the tragedy below. The well-used machinery of defence was scattered around, and watchers were bent over telescopes, alert for danger. They stood on a narrow gantry welded to the inner skin of the metal pyramid and looked out through wide loopholes. The gantry was open to the elements and a thin chill wind was blowing.

“You do not have to do this, my lord,” the older of the two men said. He was huddled inside a thick cloak that was slowly gaining a speckling of flecks of air snow. The other man was wearing a heavy samite gown, interwoven with strands of gold and silver.

“It has been my duty to watch this thing for the last ten years, Lord Gallowglass,” the other man said. “The burden has not yet fallen on another’s shoulders.”

“It will soon enough, my lord.”

“Maybe.”

“You have passed the first three hundred and twenty-five tests, old friend, surely this last one cannot be so hard?”

“The enKernelling? I understand it is . . . hard. Will you guard the door for me?”

“Of course, my lord. The Moramor and I will stand sentry.”

“Good. Your love will help keep me safe -- from whatever awaits me.”

They fell silent, and looked out into the Night Land. To the North the sky was tinged with a dull red light, and a faint blue glow painted the Western horizon. The rest of the world was lost to darkness. The Master Monstruwacan-designate leaned forward and looked down at the broken land. In the eternal gloom it was difficult to make out details, but things were moving amid the rubble -- and the children were gone.

“It is done,” the Gallowglass said quietly. “You should go back inside.”

“Yes,” the Master-designate said reluctantly.

“No good will come of this!” Essa said, brandishing the Hour-Slip.

“Be still, wife. If the council has decided to elect that young fella Master what’s-his-name, there’s nothing you or I can do about it,” Hugh Leverhede replied, secretly cursing the Hour Criers Guild. They were an unpredictable bunch at best, and one never knew when the next bunch of Hour-Slips would filter down from them. Sometimes months went past without any news. That suited Hugh: ‘no news ain’t bad news’ was his motto, and the Crier’s sudden burst of efficiency was unwelcome.

“Pass the honey, please.”

Essa ignored him. “It says here that’s he’s only thirty-eight years old. Imagine that.”

“I don’t think I can, sweet pea,” Hugh said, feeling a sudden arthritic twinge in his back. “Pass the honey, please.”

“Don’t you sweet pea me,” Essa said as she gave the pot a shove in his general direction. “Oh preserve us!”

“Now what?” Hugh asked as he spooned black honey onto his mushroom bread.

“His wife just died, poor thing, and he’s been left with a little baby daughter. Who’s going to look after the little mite while he’s off running the Redoubt?”

“I imagine that —”

“They say that he’s the first Master Monstruwacan whose grandchildren didn’t have grandchildren of their own. Makes you wonder they elected someone so young.”

“Not me it doesn’t. In any case, he’s only the Master-designate. He might fail the trials.”

“Yes, I suppose so,” Essa said, a little mollified at the prospect. “Don’t you have to be off soon? I thought you had a long trip today.”

“Aye, all the way down to the Earth Current generator. Seems they’ve got some corrosion in one of the turbines. Nothing my little friends can’t fix.”

“I swear you think more of those things than you do of me.”

“Now don’t be daft, wife. No Jackotrade colony could take the place of a warm woman on a cold night — better than a hot water bottle!”

“Hmm,” she said with a smile. “Get away with you, you old rascal.”

As he waited to be called, the Master-designate opened a small locket. Inside were two miniatures painted in vivid enamels on translucent bone china; one was of his baby daughter, Naani, and the other his wife. He touched her image. It was strange, only six months had passed since she went to the funeral plains, and he was already having trouble remembering what she looked like. He closed his hand around the locket and stood up.

Monstruwacan Lanyard entered the meditation chamber. “It is time, my lord,” he said.

The Master-designate nodded. It was only a short walk to the Kernel, which was housed inside a featureless, white-painted cube located at the exact centre of the pyramid.

He sat cross-legged on a granite plinth. The walls of the spherical room were made from six-foot thick black glass and were, so far as he could see, featureless. He had read detailed accounts of the room’s manufacture in the Vault of Ages. Written from the perspective of the Guilds involved, they were mostly heroic tales of success against the impossible odds thrown up by physics, mathematics, and chemistry. The Guild of Glassmen were especially unstinting in singing their own praises. He conceded that they had a point; the glass sphere was a masterpiece of fabrication. Although he knew, more or less, where the door had been, he could see no sign of its circular outline. It was as if it had been created to allow his entry, and ceased to exist when its job was done.

The room was lit by a soft, shadowless light that fell almost unnoticed from the walls. The annals of the Glassmen claimed that an intense, burning light had been focussed on the sphere for a hundred years. The glass had swallowed every scintilla and, so convoluted and cunning was its microscopic structure, it would take many tens of millions of years before the last of the imprisoned light had seeped through.

With heart pounding, he closed his eyes and opened his mind.

He was breath and animal electricity, sinew and blood, mind and soul, a self-ordered maelstrom working in miraculous sympathy. But it was not enough. Though strong in both the Night Hearing and the Master-Word, he needed the Kernel’s help for the task ahead. Its glass walls hid cunning designs; buried inside it lay the last great work of the Electromechanics Guild. Cautiously, he let his mind brush against the invisible filigree of superconducting wires and neural nets hidden in the glass. It was like touching a cloud of razor blades that coruscated with lightning.

Consciously, he stilled his self-awareness and joined with the machine. His perception expanded, searching for the Master-Word, that undeniable measure of all true humans. The Gallowglass and the Moramor were standing shoulder to shoulder outside the Kernel. Their purity of heart was unquestioned and evoked a thrilling race memory of the forefathers and foremothers. Lanyard and the other Monstruwacans also shone with the Master-Word, but to a lesser degree than the Lords of the Prefecture.

How ironic, he thought, that the Prefects, so strong in the essence of humanity, would not pass their seed to subsequent generations. Yet it had always been so — the Prefect’s oath setting them apart and above the petty concerns of the world.

His mind went back to the ancient labours of his people. For five hundred years, the builders laboured on the mighty metal pyramid and the delvings beneath. A hundred thousand men stood shoulder to shoulder, and repelled the beasts of the Night. Four times that many, men and women both, quarried stone and ore, smelted metal and forged girders, dug deep and secret tunnels, or wrested life from the frozen black soil. Generations lived and died as the second greatest structure in human history rose to defy the endless night. When their task was done, the surviving three hundred thousand souls stood in massed ranks around the pyramid, raised a defiant song, then retreated into their final home.

The bubble of his search expanded, rushing past the few pinpricks of humanity in the rest of the metal pyramid, out into the dark night, and downwards to the hidden homes of man. He brushed against hundreds, then thousands of people. The Master-Word lit them, to varying degrees; but it burned brightly in few. Consciously, he slowed the onward rush his awareness, the better to rejoice in their anthem, thin though it was. It was a thousand warm homecomings - laughing children, buttered toast, soft embraces - infinitely more than anything built of metal or stone, it was home.

He left comfort behind and voyaged into the dark.

At first there was nothing, then Night fell across his mind. It was worse than the literal cold and dark outside the Redoubt. It negated hope, and screamed with accusations. The cries of condemned children came to him.

For pity’s sake, how could you do this to us?

Because it is necessary for the survival of the human race.

Murderer!

Leaving the ghosts behind, his spirit swept onwards, across the ruined valley floor. There were no human songs here, just the acid pinpricks of the beasts of the Night. They were alien, and easily dismissed. In the silence his search ascended to a new plane. He found what he was looking for.

The Master-Word of Great Redoubt was distant, but strong:

Where are you, our lost brothers and sisters?

The lament of the five hundred million humans in the Great Redoubt flew across unknown, uncountable leagues, and strengthened his will. He knew it was Fool’s Gold, but he took what strength he could, then closed his heart to the great longing. Soon other voices began to nibble at the edges of his consciousness. He resisted for a short while, then opened himself to their angry chatter. It was like being drenched in foul-smelling icy water.

You know who we are.

Yes, you are the descendants of the walker tribes. Your ancestors strode beside the moving cities for aeons then, at the time of your greatest peril; we abandoned you to the night.

The shame! The shame!

You are not what I seek. We parted countless aeons past; so long ago that the disgrace of our betrayal is almost forgotten.

Not by us! Never by us!

Nor by me. The shame is eternal. Ultimately we must pay. But now you will let me pass.

Go then . . . for now. The reckoning will wait.

With an air of crushing disappointment, they subsided from his mind. He was astonished and mortified at their numbers and the vigour of their aberrant chorus, and their passing left a void like a ragged wound.

In his mind, his body took a step on the valley floor. He felt the broken stones underfoot, and the icy wind in his face. The sky was grey-black and featureless, like some giant hand had clapped a cap over the world. He knew that image was uncomfortably close to the truth. In the rarely visited western quadrant of the Vault of Ages there was a single column dedicated to the lost science of astronomy. Examining it was one secret tests faced by every Master-designate. The ancient knowledge was always perilous, but the astronomy column had mired more would-be Masters than the rest of the Vault’s blandishments put together. Exotic worlds and living suns — millions of them — vibrant in the universe’s staggering immensity. Worst of all were poignant tales of Earth’s own moon, silver and beautiful, a friend when the sun hid.

Until it was destroyed in a desperate attempt to keep the worst that the universe had to offer at bay.

The records were unflinchingly detailed about the consequences of that rash act, almost as if the chroniclers had an urgent need to ensure that history did not repeat itself. He could not imagine any circumstances that would allow mankind the opportunity. If the fabled other planets had ever existed, they were lost forever now. When the moon exploded, debris had quickly spread into an implacable barrier around the Earth. Worse still, the massive gravitational shifts had slowly, but inexorably begun to de-spin the Earth.

Hunching his shoulders against the cold, the Master followed the path of his mind’s eye. The going was hard. His imaginary hands and knees were lacerated in regular falls, and his back ached like he was carrying a great burden. The way took him by treacherous paths into dark valleys filled with things that chittered; he scrambled up razor-like desiccated rills, and along wind-swept spurs. Only from the highest peaks could he see his destination, but he could always sense it.

He strode towards the blue glow in the West that marked the Shine.

After a thirty-hour labour, Bergthora was so tired she couldn’t even hold her baby. The pain and effort, and several doses of poppy juice, had left her exhausted. The midwife held up the squalling red-faced boy while her husband dabbed her forehead with a cloth. The child looks so angry, she thought as she fell into a long, troubled sleep.

At the last moment the Master Monstruwacan hesitated. The spirits of the Night crowded close.

We will snare your soul as it takes wing. We will rend it to shreds and gobble it up.

He ignored their spiteful taunts. They were dangerous to be sure, but they were small things, with petty hatreds. Mankind had defied their gibbering bile for millions of years.

A perfect image of his wife formed in his mind’s eye. Beautiful and dying, holding their newborn baby in her arms, vowing that their souls would meet again.

He knew who had put it there. He pushed the memory away, and stepped into The Shine.

Hugh the Jackotrade Master opened his toolbox and began to slowly pick out the tools of his trade. A couple of Engineers were watching him from outside the turbine housing. He could hear them muttering, but he wasn’t about to rush on their behalf. He had spent the last half an hour fending off questions from increasingly high-ranking Engineers. In the end he had to chase them away but a couple had remained to spy on him. He shuffled around behind the turbine housing, hoping they would leave him alone.

The turbine had been cantilevered away from the Earth Current ring, but he could still feel its low vibration through the shining steel casing. It was rumoured that some Engineers slept under the ring, the better to sense its moods. It was undeniable that they had a close bond with their machines, so close that they were usually able to catch the subtle bite of corrosion long before it could cause serious damage. He needed to look closely before he could see the little pits mottling the shining blades. Although the damage was superficial, he was surprised at how extensive it was.

No wonder they’re so irritable, you’d have expected them to catch this a lot earlier.

He picked up a blue bottle half-filled with a viscous fluid and held it up to the light. A column of Jackotrades unwound from the main mass, and started to crawl sluggishly up the glass towards the light. Tut-tutting at their lethargy, he put the bottle down and picked up a rubber squeeze bulb. He sprayed the nutrient cocktail onto the turbine blade, taking care to lay trails between each little cluster of corrosion. Then he picked up the blue bottle, uncorked it and poured its contents onto the blade. In an instant, the Jackotrades spread along the nutrient trails, blind instinct leading the little machines to the places where their repair skills were needed.

Hugh sat down and dug a mushroom and bilberry pasty and a bottle of watered-down wine out of his toolbox. He would wait an hour, before using the come-to-home tinctures. He fervently hoped that the Engineers would leave him in peace until then. But he doubted it.

The Earth was gone. He stood alone on an endless blue plain. The Fixed Giants sat at the corners of an enormous pentacle with him at its centre. Their shapes embodied an idea of perfection crafted aeons before the sun died — pyramid, cube, octagon, dodecahedron, and icosahedron. He had no conception of their size, only that the dim glimpses seen by the naked eye were a fraction of their true magnitude. Their vastness extended beyond mundane dimensions. At first he thought they were featureless but as he looked again, he realised that each was built from elements of the others — cubes inside pyramids inside octahedra - endlessly concatenated — winding back to find their origin had moved - had never really existed - a perpetual dance marrying energy and form. His consciousness expanded, letting him glimpse the true nature of the Fixed Giants.

They had existed since the universe cracked open, and they expected to survive its entropic death agonies. He couldn’t comprehend how that was possible, and was terrified, so they anchored him to his own scrap of consciousness.

It was a small kindness.

He looked at the square and found himself staring back from the octahedron. His viewpoint encompassed the universe. Everything was in motion: stars, galaxies, living things, atoms, fractions of atoms, always searching for a new equilibrium then darting on, never satisfied.

They took him back to the beginning.

The universe exploded to life, birthing quick-burning, short-lived stars that destroyed themselves in fiery conflagrations, spreading their essence across the galaxy. He rode a burning wind pregnant with newly created heavy elements. They were inconceivably rare, but they tugged at each other and slowly, over vast gulfs of time, accumulated. Near the young stars, thousands of metal-rich protoplanets jostled for elbowroom. Collisions were frequent, and violent. Soon the deceptive peace of the solar system’s babyhood was banished as billion-year long bloodbath of planetary formation and destruction began.

Further out, the giant planets were accumulating mass in a more sedate fashion — a hydrogen atom here, a water molecule there - they had time on their side. Aloof from the fiery maelstrom, their evolution was less hurried, but perhaps more sure-footed.

His guides hurried him along.

“Let me see.”

They ignored him.

Three billion years before his life began, he stood on the shore of a foul-smelling sea; the air was thick with volcanic dust and sheet lightning cracked perpetually across a rain-lashed sky. In the seething, sulphurous water simple molecules jockeyed for position, driven by the blind laws of chemical equilibrium and electrostatics. For aeons the random forces of nature threw up countless variations. A tiny fraction gained prominence for an instant then fell back into the seething equilibrium. Eventually, a molecule containing a five-ringed sugar, a phosphate group, and nitrogen-containing base bumped into a similar structure. The chain grew, and miraculous things began to happen. The new molecules of RNA shepherded amino acids together, weaving them into protective membranes. Soon, simple catalysts emerged. A mere half billion years later the first simple cells appeared, and a cosmic eye blink later humans cracked rocks together to make fire, and dreamed of the stars.

The dream quickly died. Twenty million years of stagnation followed.

Monstruwacan Lanyard walked around the Kernel, his hands clasped behind his back and his head bowed. A gaggle of Monstruwacans burst into the room. Lanyard noticed the subtle hand signals flicking between the Moramor and the three Prefects guarding the Kernel.

“How long has he been in there?” Monstruwacan Cambyses asked.

“Three days and four hours and sixteen minutes,” Lanyard replied.

“This is a day past the normal time. How do we know he’s alive in there?”

Lanyard shrugged. “The annals suggest that the Kernel will open automatically in the event of the death of the designate.”

“Naturally, the annals can always be believed,“ Cambyses sneered. ”Curse this waiting, I’ve half a mind to go in there and drag him out.”

“That would be inadvisable, my lord,” a new voice said.

“Ah, Lord Gallowglass,” Lanyard said, with a small smile at the back of the rapidly departing Cambyses. “Welcome back. I fear your wait is far from over.”

“It will be over when it is over, my lord.”

“Your stoicism does you credit. Some of my fellow Monstruwacans are getting impatient. That is understandable. The Master-designate is somewhat of an unknown quantity. He has only been a member of our order for twenty-four years — hardly enough time to get to know him.”

“I’m sure you — and your fellows — have complete confidence in your candidate, my lord. Otherwise why would you have elected him to the highest office?”

“Your are correct, Lord Gallowglass,” Lanyard said smoothly.

He blinked — and found himself at the centre of the Circuit of Assessment. However, there were subtle differences. The walls and floors were still dead white, and soft white lights hung from the domed alabaster ceiling. But there was no sign of the circle of testing stations, with their banks of white dials with flickering white needles. The talc-faced Testors in their white smocks were also absent. He felt a slight pang of relief at that: even thirty-three years on, he still had the occasional bad dream about his Day of Assessment, and the Testors were always prominent in them.

“Why have you brought me to this place?” he asked.

What is the nature of the human soul?

He laughed. “You would catechise me on the nature of existence? I feel inadequate to the task.”

What is the nature of the human soul?

“Very well. The soul is immortal and emanates from a single universal principle to which it is destined to return at the end of life.”

Always?

“There is a tradition that some soul-pairs are bound by love and will return to inhabit new bodies until, after aeons, the lovers unite.”

Did you share such a love with your wife?

He hesitated a long time before answering. “No. Our love was true, but it was for a single lifetime.”

Is this humility?

“Do not be absurd. Why have you created this place?”

A dislocation passed through him, and he was standing in the Vault of Ages. Four black pillars, their crowns lost in the gloom high above, surrounded him. Black writing, in a thousand ancient and forgotten languages, flowed over their ebony surfaces.

You know this place.

“The four pillars of Heresy. Examining them is the sixty-second trial of a Master-designate. A dull exercise, perhaps that is why you have added these florid touches?”

Tell us about your heresies.

He pointed to the pillars in turn. “Primus: man is a fallen spirit who has forgotten his own divinity. Secundus: on death the soul may pass into the bodies of animals, even plants. Tertius: Transmigrations of the soul are tiny incidents in the great drama of world annihilations and restorations that occur over enormous periods of time. Quartus: the restoration of humanity depends both on human ethics and the performance of meritorious acts by an avatar of godhead.”

On an impulse, he leaned forward and touched Secundus. For a moment the writing flowed over his hand, then the pillar’s dark animation died, and was replaced by pictograms and studded metal rings.

“Why the mummery? Is this test just a show with mirrors and smoke? If this is the great secret that you hold in your cold hearts, them I have to —”

Why did you touch Secundus?

Before he could answer another dislocation swept him away. He was standing outside the Lesser Redoubt. The Great Door hung from its hinges and the pyramid was dark and silent. The hundred foot thick iron walls were gnawed through by red-brown corrosion.

Another dislocation. He was standing on the ruined land at the base of Redoubt Hill — and his people were fighting for their lives. With suddenly preternatural vision, he saw every detail of their ordeal. The Prefects had formed a running phalanx, their Diskoi ladling out generous helpings of death to the beasts of the Night. But their valour wasn’t enough. His people’s path was strewn with the bodies of the fallen, and hideous things were gleefully picking them over. He glanced to the West where the blue glow from the Shine washed over high, unscalable cliffs. When he looked back, the Prefects had been broken. Hairy beast men shrieked with joy as they fell upon the humans.

Unable to watch any more, he hid his face. The earth under him was slick and chilly, and buzzed incessantly. A thin, icy wind carried the dying screams to him. Shamed by his cowardly refusal to witness the end of his people, he steeled himself and looked up. The battle was over. The Earth was stained by a five-mile long trail of blood. Oddly, the beasts of the Night were running away from the carnage. Sick to his heart, he realised that he could sense their feelings — they were terrified.

He examined the knot of pain eating at his heart. What he felt wasn’t the Master-Word. It was something else.

“Secundus?”

There was no reply but his words took wings like an Exhalation and filled the Night Land.

Among the ruin of his people, someone had survived. His vision blurred, and was reduced to peering myopically at the figure walking serenely through the ranks of monsters. He couldn’t even tell whether it was a man or a woman. Whoever it was, he or she had an air of connection to everything in the world. He had been terrified by his own glimpse into the hearts of the inhuman hordes, but this person was possessed of another order of consciousness entirely.

“Who is this?”

A human born within the last year — and a hope for the future of the world.

“A child of the Lesser Redoubt? What do you mean the hope of the world?”

The child represents a novel — and surprising — iteration of humanity, and is the final chance for your species to fulfil its potential.

“We have managed for twenty million years, we survived the stilling of Earth’s rotation, the fall of Night, and the death of the Sun—”

Irrelevant — your greatest achievement has been millions of years of stagnation — and your days are numbered. Your pitiful metal tent is failing. Even the Great Redoubt is doomed. Their decline is slower, but no less certain. Humanity has nearly run its course and the universe will hardly notice its passing.

“What can one child do?”

The child is not alone. Another has come into this world — you know where.

“The Great Redoubt. They outnumber us ten-thousand-fold.”

Numbers are irrelevant. Chance is everything. If this special child survives to maturity, and if it meets its soul mate, their genes will cascade down future generations. Humanity will have a small chance to regain its lost vigour. One day your species might even realise its true place in the cosmos and, eventually gain the strength to reach out into the wider universe.

Laughter rose in Master-designate’s breast. He folded his arms over his chest. “Well, what you ask of me is a simple matter. All I have to do is find this child — one among hundreds — ensure it grows up; then deliver it to the Great Redoubt, which has been lost to us for eight million years. Even if I knew where it was, there is the small matter of the countless leagues of the Night Land, with its untold horrors to —”

We will ensure the child’s safety.

“You need this child as much as humanity does.”

You are placing interpretations on reality based on your limited knowledge of the universe. The concept of need is redundant in our terms. Will you pay the price to save the child?

“What is the price?”

You must destroy the Lesser Redoubt and cast your people into the Night Land. The hammer and anvil of Darkness will decide who is worthy.

“Impossible. How can you expect me to commit such a crime?”

Signs will be made evident to you. The price must be paid.

The Master-designate sneered. “That is not good enough — I cannot be expected to make guesses —”

What single achievement would you want to stand as your monument?

The answer was so obvious that he spent several moments trying to find hidden meanings in their words. In the end he decided that the question must be without guile, or if there were any, it was behind his comprehension.

“If I survive this test, I will seek what every Master Monstruwacan during the last eight million years has sought — the building of a working Master-Word machine.”

Why?

“So we can regain contact with the hundreds of millions of humans in the Great Redoubt, so we can unite humanity and, ultimately, cast you and your kin from this planet.”

A paltry ambition.

He stood on the frozen broken plain. The frigid wind scoured his face with sharp blue snowflakes that stuck to his skin and refused to melt, sucking the heat from him. The Fixed Giants looked on, impassive as mountains.

“What do you mean?” he shouted.

There was no reply.

The Master Monstruwacan climbed out of the Kernel and looked straight through the waiting Prefects. They saluted, but he did not notice. Nor did he notice the ranks of kneeling Monstruwacans. A man carrying a ruby-coloured robe approached him. He said something, but his words were unintelligible. It was as if an insect had learned to speak. He laughed at the idea of the man rubbing his legs together, frantically producing staccato stridulations. The man draped the robe across the new Master’s shoulder and pushed his face close. There was something familiar about his eyes and the look of concern on his face.

“Lanyard?” the Master said, his comprehension returning, along with crushing disappointment. He was one of the insects.

“Yes, my lord. You are alive, we were sick with worry.”

“I was only in there a few minutes.”

“My lord, you were gone of the best part of a week.”

The Master pushed Lanyard gently aside. Distantly he realised that his body was a mass of aches and pains, and he was desperately in need of sleep.

“I must take my rest now, Master Lanyard. When I rise I wish to speak to the Gallowglass.”

“And the Monstruwacan Council, my lord?”

“Maybe later. The Gallowglass first.”

As he limped out of the room, escorted by a pair of Prefects, the new Lord of the Redoubt left behind the frenzied whispers of his fellow Monstruwacans.

The Guild of Ancestors was one of the smallest and least prestigious of the Lesser Redoubt’s two hundred and six Guilds and Orders. It had three dozen active members, and several of them were over a hundred years old. The air in their tiny Guild House was thick with dust and the savoury tang of varnish and glue. The Master Monstruwacan and the Gallowglass had to stoop to avoid banging their heads on the low wood-beamed ceilings.

“Who is in charge here?” the Master asked.

A glance propagated down the ragged line of Guildmen in front of the Master, before settling on a bald man who took a reluctant step forward, gulped silently a couple of times, then puffed his chest out.

“I am Hobnil, Master of the esteemed Guild of Ancestors.”

The Master bowed slightly, setting off a wave of bowing and scraping by the Guildmen. One of them surreptitiously handed Hobnil the sacred Almanac of their calling. He held it close to his chest like a shield.

“Thank you, gentlemen. I would ask you too leave now. I will to speak with Master Hobnil in private,” the Master said.

The Guildmen reluctantly shuffled out of the room, with many a backward glance. Individually, they were weak in the Master-Word, but collectively the Master could hear their unspoken annoyance. Beside him the Gallowglass was bristling with suspicion.

“Ahem, Master?” Hobnil said, nervously.

“I have a job for your Guild,” the Master said. “It will suit your unique talents —”

“We are eager to serve, my lord!” Hobnil said, a little too quickly.

“This thing must be done in secret, and no word of it must pass beyond the confines of your Guild House.”

Hobnil’s face fell. “Yes, Master, I suppose we can do that — I mean — whatever you say, my lord.”

“Good. The Gallowglass will advise you on security measures.”

Hobnil visibly blanched at this idea, and there was a clatter from behind the one of the room’s closed doors.

“It seems that there is much for the Gallowglass to do,” the Master said. Hobnil nodded his head dumbly. “You keep records of all children born in the Redoubt —”

It was not a question, but that did not stop Hobnil answering. “Yes, my lord. Births, deaths, marriages, Guildings —” He saw the look on the Master’s face and stopped talking.

“I want you to keep watch on all of the children born between one year ago and one year from today. I want a report on each child every six months. I want to know about their growth, their accomplishments, their friendships, their beliefs, their performance in the Circuit of Assessment — anything that speaks of their future lives.”

“But, my lord, we are not equipped to gather such information, my Guild’s high reputation is based on the storage of genealogical knowledge, we are ill-equipped to act as, well —”

“Spies? You are correct, that is why I have today promulgated a decree granting you the extra funds needed to expand the size of your Guild six-fold.”

Hobnil beamed at the news. “My lord!”

“Of course, such an increase in status will not pass unnoticed, and will certainly lead to petty jealousies among some other Guilds. To avoid too much scrutiny of your secret work, the decree also requires you to apprentice girls. That innovation should be enough to deflect attention away from matters I want hidden.”

Hobnil tilted his head to one side, then to the other, as if he was trying to hear a faint, distant noise.

“I am sorry, my lord,” he said eventually. “I must have misheard — girls?”

“Your hearing is adequate, Master Hobnil. Most Guilds will eventually be expected to recruit female apprentices, but yours has the honour of being the first. The interest that this innovation causes should be enough of a smokescreen. In any case, the task will require women; there are many situations where a man would stand out like a sore thumb. The care of young children for example.”

Master Hobnil nodded, his eyes focussing on mid-air.

“Good, now I will leave you in the capable hands of the Gallowglass,” the Master said. “You should know that his Prefects have already taken up defensive stations around your Guild. This heightened security will help in the changes that are needed.”

“Yes, my lord.” Hobnil said gloomily. “One more thing: you say you are interested in all of the children born during these years — I assume the edict does not include your own daughter, sweet little Naani?”

“Yes, it does. All of the children — no exceptions.”

“Yes, my lord.”

To A Mouse in the Walls of the Lesser Redoubt (Part 2)

© 2002 by Nigel Atkinson.

Image copyright by Stephen Fabian.