Imago (Part 2)

by

Brett Davidson

Descending once again, Ael sat through the acclimatisation stops with a grim determination. It was something to which she was going to have to become accustomed. She was certain that her plan had worked and indeed, when she returned to school, she showed the symptoms of pressure sickness and the nurses almost sent her home again. Her father and brother, returning from their own tour, were at once too exhausted and excited to even think that she might be lying when she said that she had been at home in bed the whole time.

It was at this moment of success that she realised that she was not who she thought she was. There was someone named Ael in whom everyone believed, but she was just a costume and the creature that inhabited that costume was some sort of nameless ghost or imp. She had thought a day ago that this imp wore her, but now she began to think that she was that imp herself now. It was most strange, but it gave her imagination a certain freedom that she had aspired to as a poet, even if at this stage she could not find a true name for herself. ‘Ael’ would have to do for now, with or without quotation marks.

The outline of a plan came to her from underneath her conscious thoughts as she pondered on her odd condition. It was obscure but compulsive at first, and swiftly become concrete and she realised that it was but the logical extension of her first trip to the heights.

The next day in class, her Sisters were much impressed with the energy that she showed, though they were rather critical of the way in which she applied herself. They reminded her that she would be sitting guild examinations next year and she should decide soon about which courses of study she should take. As it was, she was far too uncentred. “I’m to be a librarian,” she lied merrily. “I’ll want to read all, especially books historical and cartographical, plus those biographical and mythological.” They shook their heads, but delivered the texts that she requested nonetheless.

Later, she took her notes home and began to piece them together. She was sure, from what she had read, that the settlers who’d left the Great Redoubt ages ago had set off for the North with the intention of building their own arcology in the more clement lands that were supposed to exist there. There was even an estimate of how far the expedition might have penetrated, or at least of its absolute limit to its range, which was just within the range of a well-charged airship of current design.

The maps themselves were of good quality, within the border of the horizon as seen from the top of the Tower of Observation. They detailed all the visible threats of the Night Land, noting especially the vast Watchers and the dreadful House of Silence, but these were of no concern to her. Sartor’s airship would fly above these things, or swoop by so fast that they’d have no hope of stopping it.

Before she slept, rising naked from her bath, she realised that she was frightened. The water lapped about her calves, cooling.

Of course the plan was vague, but it was simple. Complications were excuses not to do something. She could commit herself to the simple plan and adapt to contingencies as they went a long, or she could stop everything now. She would not make up excuses; the two of them would go on this expedition. The Lesser Redoubt had the overpowering reality of all things that existed just past the limit of sight.

She dressed herself and hurried to her room to continue her calculations where she saw that the hawkmoths were finally freeing themselves of their soil beds. Bodies bigger than her thumb pulsed as they pumped blood into their new wings and on the backs of their thoraxes, white patches that resembled skulls or masks stared up at her. They were Archerontia atropos. Atropos, meaning unturning. Yes, she would be changed and would fly just like them and never turn back. She opened her window so that they could escape.

For a few frustrating weeks, Ael and Sartor only spoke over the slip network. The days when she would be free from the Sisters’ observation were yet to come and sickness no longer a tenable excuse. Fortunately her father was too preoccupied to log her calls. Indeed he now seemed to live in constant pursuit of eternal daylight under the wandering suns while she had long nights alone with the face and voice of Sartor. She saw this partition of light and dark as a symbol of the separation between the worlds of herself and her father, and a sign of her unity with her beloved, though a mere sign was no substitute for his real presence.

What he had to say to her was a further disappointment: “The Watch is ending all flights. They’ll announce it on the hour slips a decent interval after the Exhalation.”

Ael was exasperated. This was not how it was supposed to be. She had not even told him of her plan yet. “What? Why? Didn’t you say no?”

He shook his head, nodded. “Of course I said no,” he said. “It didn’t do any good. The decision was made high up by the Monstruwacans.”

“Oh, and what had they to say?” she demanded.

“They said that the air is too thin. It has been thinning for millions of years and now they have decided that it is not worth the risk of flying.”

“What nonsense, what so say! They could... they could do all. They could, I see, I think, they could find the Lesser Redoubt!”

“If it still exists...”

“How to know if there is no search? What of the heroic creed? Men go Out into the Night Land and are feted for nothing more than killing a few spider crabs. Even criminals go Out and return pardoned! We send butterflies Out! Criminals and butterflies, but not women!” She almost stamped her feet.

“And certainly not girls.”

“I’m not a girl!”

“You are, Ael, and will be for a little while yet.”

She would have slapped him if she could reach through the screen. “And what of you? What do you say that you will do?”

He shrugged. “I don’t know. Train endlessly, maintain my machine, put on the appearance of a hero and try to impress young girls.”

She laughed at him so that she might not spit, but he was just as bitter as she.

It was afterwards that her impish self realised that this situation could be an advantage. No one had expected her to visit Sartor on her own and thus it had been easy. Now no one expected an expedition to the Lesser Redoubt and therefore the two of them could flee there without the encumbrance of lengthy plans and the eyes of escorts. Delight overcame her as her mind spun strategies. Her only regret was that she had to trick Sartor, but she knew that he would understand sooner rather than later.

The days of festival preceding the Exhalation came at last and classes were terminated. Ael was supposed to be sequestered at school for the guild examinations that were sat by all who had not already been granted positions by inheritance, or for various reasons had renounced them. Ael threw the loaded dice in her head and took the lift to see Sartor.

“I’ve got a present for you,” he said with a strange furtiveness when they were alone in the hangar.

“What is it? Say, show what you have!” she demanded, slipping once again into the embarrassing alliterative dialect of the Fields in her excitement. Maybe he had thought in parallel with her and they were going to fly away this very night!

He turned and took a bundle out from under the pilot’s seat. It was another flight suit.

“Where did you get that?” she gaped, reaching out to touch it, but not daring to take it. So I was right, she thought. He shares my intentions after all!

“I made it. We make our own, I took an old one of mine and stitched and sewed a bit. I knew that you were about my size, I guessed how you might be shaped differently and I let the adjustment of the straps and fastenings make up for any mistakes that I’d made.”

“For me?” she asked redundantly.

“Do you want to try it on? We can’t fly together now, maybe we never could, but you could wear this and imagine what it was like.” He shrugged. “I know it’s absurd, but I really did think that we could have flown.”

So now the gift was a substitute. The childish Ael would have accepted that; she would have cried and even fought, but she would have been bound by dull fact in the end. Ael the imp however though saw this as another opportunity to make new facts. The suit was only a substitute for a flight now, but already she guessed that if he was willing to make it for her, she could twist the substitution into the real thing. She took the bundle and let it fall open. Was she going to put it on here and now? She would have to take off her own clothes first, and she certainly wasn’t going to do that. The idea seemed somehow too casual without some form of symmetry. “I’ll wear if you unwear,” she said.

He laughed. “Now why would I do that?” he asked.

“Something must be equal.”

“How is that equal? You’ll be my equal if you put it on.”

She clutched the flight suit to her, already feeling naked. The mass of quilted fabric held close already felt like some double of his body, which was most disconcerting. “You’ve been disfigured, haven’t you?” she blurted.

He was taken aback by that. “Have I?” he quipped. She was sure that he was hiding something.

“That’s why you won’t unwear,” she went on.

“I undress every day.”

“But not for me.”

“That’s because we’re not married. It wouldn’t be proper.”

“Suppose we were married, hmm?” she suggested. “What say then?”

“We barely know each other,” he pointed out. “I only met you a few weeks ago.”

“How can you so say?” she cried. “I know as if we’ve known each other forever!”

“You’re exaggerating. Young people always say that.” He laughed nervously, possibly regretting his gift now.

“If not in this life, then another. I don’t know, I don’t care. It’s forever now.”

“Maybe,” he admitted, possibly more in resignation than acceptance.

She’d won something, but she wasn’t sure what and she was now bound to put the thing on. “I won’t let you see me,” she said, insisting on some form of balance.

“I won’t look, then.” He ostentatiously folded his arms and stared at the hangar door, but Ael ducked behind the body of his airship anyway. Removing her own clothes was easy enough, but the flight suit was a complicated thing with its own peculiar ties with a set of specialised undergarments and she had to stop and partially disrobe a few times to be sure that she even had things on the right way around. Even then she was not sure whether she could get everything right and she dithered with several fastenings untied and buckles hanging loose, red-faced with frustration and ashamed to ask Sartor for assistance. In the end, she waddled out to face him, feeling as bloated as a caterpillar. Of course he laughed at her, making her angry.

“What a funny little pupa you have made, then. Will you be a moth or a butterfly when you emerge?”

“Who’s to think I will emerge? Have you?” she said in pointed reminder of Sartor’s persistence in refusing to even loosen a button in her presence.

He ignored this, or at least overtly. “I’ll call you moth anyway, just in case. You want to fly in the night.”

“And I will!”

He sighed. “Moth,” he teased, grinning.

“No!”

“Moth!”

“Stop it!” She pinched him, or tried to and was thwarted by the thickness of his own flight suit.

He laughed again. “Really? Do you want me to?”

“... no.” She let him finish for her, correcting her mistakes. At various points he slipped his hand underneath the outer layers and she squirmed, not sure whether he was being lecherous or practical, nor whether she should be affronted or thrilled.

Finally, as he was tightening the final set of cords behind her back, she wrapped her own arms around him and looked seriously into his face. He immediately realised her intent and froze. His eyes were black and shining, like ink. His lips parted as if he was about to say something. He’s only a boy, she thought. He’s afraid of me. They continued their embrace for a while until he finally permitted her to loosen the straps of his gauntlet and the cuff of his undergarment. She found underneath a delicate wrist, pale and softly downed. His veins were like pale blue traceries. She stroked his skin, touched her lips to it. He sighed and she kissed his neck, the muscle that ran from his ear to his collarbone and then struck like a serpent. “I have an idea,” she whispered in his ear.

“What’s that?”

“The Monstruwacans’ banning is just so say, isn’t it? So they say you can’t fly, but they can’t stop you, can they?”

“They can stop me easily.”

“Only if they know.”

“Oh.”

She smiled, hoping that in acceding to this conspiracy, he’d become complicit in a more visceral collusion. If not, she’d use those words in a tragic poem about unrequited love. She kissed him again. “Mmm... What say you now then?”

“Where would I go? What could I bring back but a stone?”

That was nonsense. He knew that he wanted to go, stones or no stones. Anyway, she had a brilliant idea. “Where we could go,” she corrected, “is the Lesser Redoubt.”

“No, nobody knows — ”

“True! Thus we’ll heroes; you will be King and I will be Queen!” She bit him before he could disagree with her.

Ael had never invited Sartor to visit the Fields because it would only have seemed to drag him down and shatter his myth. Now, somehow, her own myth was broken. Standing in the portals of the home lift station for what was probably the last time, with the disembarking passengers spilling out around her, the golden light of the artificial suns struck her like a chill. She felt profoundly out of place, which was what she wanted to know, but not to feel.

Appearances of beauty and falsehood conflicted in her senses. Through the towering stone and metal forest of the subterranean Fields, a half dozen of the hanging lanterns sent criss-crossed shafts of light through the living clouds of butterflies and diamond-bright flares from the windows of the spiral towns festooning the piers. Across the green landscape of the floor, myriads of scarlet banners were dotted like poppies in a meadow. The breeze brushed her cheek and was filled with the scent of flowers, carrying with it the echoes of distant festivities. Somewhere Masquers would be enacting mystery plays and revellers would be uncorking bottles of new mead and millennial wine. It was at once too intensely real and unreal as if it was reflected in a mirror, with left exchanged for right and all sense of direction lost. From the Night Land a shadow of the future had fallen across her and indelibly stained her being. She raised her veil, but still felt that she could neither touch nor see any of this now without feeling that some fine, invisible film of darkness coated her skin and clouded her eye.

A hand touched her arm and she started.

“Where have you been?” It was Feste, whom she had arranged to meet. “Maia sees your absence, the other Sisters know, and now they’re all seeking and so forth!”

Ael looked at her. “I cannot tell,” she said.

“You can tell, you can tell me? Surely I am your friend?”

“I do not know exactly where I have been.”

“Ael, you affect to speak like one of the Cap Dwellers,” Feste said.

“No, not even one of them...”

“Changeling? Has your Aviator taken you Outside?” Feste inquired. “Or has he taken you inside?”

Ael barely recognised her friend, and it was this lack of affect more than her anticipation of loss that distressed her more. “Goodbye,” she said, and turned back to the station.

“No, come!” Feste cried.

“I only came to go,” Ael replied, and left.

The preparations and festivities of the day of the Exhalation, always a time of excitement and confusion provided perfect cover. Ultimately, the object of the Redoubt’s security was to prevent any unwelcome influence from entering, and at a time when a significant portion of its biomass was to be deliberately expelled, their escape was almost easy.

The aerodromes were the obvious vents for the Exhalation. Chemical lures were atomised and forced out through the hangars and launching ports by fans in such thick concentrations that she could almost smell them. Her ears popped as the Redoubt’s ventilation system built up an overpressure and in the great ducts at the rear of the hangar, she could hear the faintest whisper of the rising flight of butterflies. Most of the aircraft had been wheeled out of the way to provide as clear a route as possible for the escaping insects, except of course for Sartor’s, and had the hangar boss been there, he would have been enraged at this. He was not there, however, and the aircraft had been moved out of the way according to his orders and his satisfaction; Sartor had simply moved it back to its launch position as soon as he had signed his report. The boss would have been even more furious to have seen a civilian such as Ael there, she knew. The penalties would have been severe; disgrace and imprisonment for the both of them no doubt, but they were escaping before they were imprisoned. Reverse causality, she thought, and giggled, intoxicated by the pheromones and her own adrenalin.

Sartor was crouched under the aircraft already, disconnecting the charging cables and unlocking the catapult cradle. Ael ran to him and he ushered her aboard. The machine smelt of ozone and lubricants and it creaked and flexed under their weight, though not as if it were frail, but as if it were the body of sensitive lover responding to caresses. Quickly he buckled himself into the pilot’s seat, seemingly making himself a part of the machine, or making the machine an extension of himself. She squeezed into the space behind him, her legs spread awkwardly to either side, his elbows against her thighs and imagined that the safety restraints around her waist and shoulders were his hands multiplied.

“Are you ready?” he whispered, his thumb on the launch trigger. The instruments lit up and cast coloured reflections across his polished helmet. Already the props where whirring into life and the whole machine vibrated about her, transmitting that vibration to her and making her anticipation tangible. The airlock doors opened, revealing the darkness of Outside like an enormous eye or a mouth ready to swallow them. Around them, the first butterflies began to appear, their wings lightly rustling against the canopy.

“Yes!” Goodbye, goodbye, she thought. I’ve sold my world, so goodbye to all that I am and never was!

He flicked the trigger and they were flung forward, out of the bay and into the Night Land. At first, the acceleration of the catapult pushed her hard back against the rear of the cockpit and then, as it released, she was thrown against her straps in the opposite direction. About her, the structure of the airship creaked as its wings stretched to catch the air. The dark ground rushed up towards them and then they gained lift and their plummet became a soar and a climb. They were flying, truly flying. She whooped for joy.

The Exhalation burst from the colossal arcology, a great shout of light and life against the dark and the cold. Lit by the glow of the its many lamps, the great golden swathes of butterflies poured from the vents in every side of its armoured hulk with an odd, almost fluid effect, first forming an enveloping nimbus of light and then billowing into the air so that it appeared as if the Redoubt had caught fire and exploded. An outside observer, and there were many, would have seen some sort of emergent order in the Exhalation as it expanded; myriads of milliards of butterflies were gathering in rippling curtains and veils that blended and overlapped and swelled outwards in pulses of light that synchronised in a slow and beautiful rhythm. Underneath the Exhalation there rose a sound like an ocean; the cry of millions of unified and joyful voices. A visitor from aeons past might have recalled a thermonuclear explosion, learned that this was a burst of life rather than malignancy, and drowned wilfully in those voices.

The cloud began to spread over the Night Land, warmed for a while by the heat of the Redoubt’s lamps, but as it diffused further and further, the light became attenuated and cold and the butterflies beat their wings less energetically, they shone more dimly and then they began to fall. One mote, not a butterfly but a Death’s head hawkmoth, flew farther and did not weaken, tapping rich stores of the earth current held in its own power cells. It soared over the land, climbed, looped slowly around the Redoubt almost as high as the finial Tower of Observation and the Final Light at its peak and then winged its way into the darkness of the North.

The Monstruwacans in their tower tracked it for a while until it was lost to even their sight.

About her the machine thrummed and the rotors threshed tirelessly against the air, carrying them onwards. She hugged Sartor from behind, wishing that she could be in his arms, knowing that she was. Onward they flew and everything she saw was nothing that she’s ever seen or imagined before.

The Night Land scrolled below like an animated map, but it was real. It was at once more hideous and beautiful than anything she could have imagined. Painted largely in tones of black, it was ornamented and textured with points and smudges of illumination. In some places there were great rents in the earth, their depths filled with writhing flames and pustulant lava, while elsewhere odd little points of light generated by living beings clustered and moved and flickered. Once they passed over an almost perfectly regular hexagonal grid of bright green stars; then they flew by a braided tracery of dim mauve that flowed like a thick liquid down a gentle slope, painting the eroded contours of the land to either side. Beyond that there was a complex pattern of jale and ulfire that sported in the labyrinthine foothills of a Watcher, barely on the edge of perception and soon lost in their wake as they fled over a great slope towards something even stranger, something that shone and glittered like a plain of metal: it was a sea.

The waters unfurled in surf, then rolled on and on seemingly forever. Waves sparkled with marbled bioluminescence, lapping against the edges of ice floes and making her drunk with wonder, hypnotising her.

She realised that she’d fallen asleep when she was jarred awake. The waves were choppy now and in the distance a volcano emitted a column of ash and steam that leant over the sea, its heavy belly illuminated a deep and threatening ulfire and red. “What’s wrong?!” she cried.

“Turbulence!”

“Can’t we climb above it?”

“No, current’s too low.”

“I calculated!”

“There’s not enough, not enough to climb if we want to get as far as...” He didn’t finish his sentence and concentrated on his piloting. Wisely, she didn’t distract him.

The airship was shaken some more and her stomach leapt, a sensation that she’d experienced for the first time only hours before when they launched on their flight. She hadn’t liked it then and she liked it less now and vomited immediately. The liquid splashed over Sartor’s shoulder and down his back, but he didn’t notice or ignored it. “Sorry,” she mumbled unheard, and retched again. Eventually her stomach was empty, but still she heaved and coughed. She didn’t dare speak up and there was no point anyway, so she decided to endure her misery. It was just another lesson in heroism, after all. Heroes don’t care about being sick.

The airship spun again, there was a roar and a noise too sudden to describe and she struck her head against the canopy.

When she woke, it was still quiet and still and she was cold. The stink of her own bile assaulted her nostrils, mixed with other body fluids. There was a metallic tang, like the taste of copper which she knew was blood. Almost every part of her hurt, but nothing seemed to be broken. She could hear the rumble of the volcano in the distance, the lap of waves on a shore, and her own rapid breathing, but nothing else. That nothing else was clamping itself about her like dread. “Sartor?” she asked tremulously.

Sartor didn’t answer.

“Sartor!” She put her hands on his shoulders and shook him. He was as limp as cloth, his head lolling. She let go. Her hands were wet.

“Sartor, please...” Coils of chilly realisation twisted in her belly and she had to get free. Gingerly she began to free herself from the binding straps and achieved as she did, albeit temporarily and tenuously, a certain detachment by focussing on this simple immediate task. She found the release for the canopy and climbed out where, for what it was worth, she could survey the damage.

She was surrounded as far as she could see by water as the waves breaking on the shore stirred sparks and pulses of bioluminescence from tiny creatures that lived in the water. They had collided with the peak of an island not far from a long, straight shore that she could see to the North. Perhaps Sartor had tried to make a fall to dry earth and almost succeeded.

Almost was still a failure. She began to walk around the wreck. The nose of the airship seemed to have taken much of the initial force of the impact and it was simply a freak of physics which had left her and not Sartor in a relatively undamaged cell of the vehicle. The great shining wings were crumpled and torn, one twisted almost entirely from the body of the aircraft and pointed directly up into the sky while the other was raked back against the fuselage and the props were almost tied in a knot. Even if... there was no chance that she could fly anywhere from here now. None at all.

It’s like a dead and crumpled butterfly, she thought, and I have crawled out of it, as if I metamorphosed inside it. She giggled and then stopped before the laugh became hysteria.

The wind was rising and even under her flight suit she shivered. Her head spun and she doubled over, retching and heaving once more. A little mucus splattered on the ground. At least there was no blood. None of hers, anyway, but she stamped on the implications of that thought. Heroes didn’t have thoughts, they dealt with facts and she knew what the facts were. This situation had been thrust upon her like an unwanted garment, but she would wear it as best she could. Yes, that was right, she told herself, her thoughts turning in odd circuits again as she tried to ignore the fact of her renewed imprisonment on this tiny redoubt. I’ll be a civilisation of one, she thought. Clothes make the man, the situation makes me, I’ll match my face to my mask...

There was a splash and something black and serpentine emerged from the sea. Its fore end rose and bobbed and a pale tongue flicked out like a tooth-edged sword. “Glut!” it said and advanced. Ael scrabbled back, but it had her scent and continued, still cutting at the air. “Glut! Glut!” it repeated. She broke and ran for the airship and rifled amongst the wreckage of the cockpit. There was an emergency kit, she knew. There were medicines, food — and there was a weapon.

She found a lightweight diskos with a helical blade, flicked the trigger integrated with the grip and it came to life with a high-pitched whine. In the blue glow of the spinning blade, the horror was larger and nearer than she had thought, and she was almost within range of its flicking sword-tongue. She stepped back and was stopped by one of the crumpled wings. The thing crept closer still and she was trapped. Its open mouth swallowed her scream.

“Glut!” it said again and the tongue flashed out. She dodged it by an inch and it skewered the wing, tangling itself in the torn fabric. Before it could withdraw, she clumsily swung the diskos down and severed the appendage almost by accident. Shredded flesh and hot ichor splattered her face. The beast gargled and shrieked, its breath foully wet. The weapon, with so much inertia bound up in the spinning blade, seemed to have a life of its own and she had difficulty controlling it, but she nonetheless succeeded in swinging it around again and again, hacking into the body of the creature. It began to writhe spasmodically, probably mortally wounded, but all the more dangerous for that. Twice she was almost crushed against the ground or the wrecked airship before she seized an opening and leapt free to run across the fuselage where she watched its agonies subside. It took a long time and she didn’t dare return to hasten the process.

Eventually the beast ceased to move, but she remained at the tail of the airship. Every part of her ached, from the crash and from the battle. She groaned in pain, and them allowed herself to cry. She wondered if in a future age some hero would come this way and find the wreck and the remains of Sartor and herself and wonder why the airship had fallen. She hoped that they would. She hoped that someone would do better than they had and make it further and achieve some great, truly heroic goal and then carry word of what he had found back to the safety of the Great Redoubt.

Something within her became as brightly active as the blade of the diskos. She looked up and out. From her new vantage, she could see all sides of the island now, and it wasn’t an island. The glowing waves described not a circle but a loop: there was a thin neck or causeway linking the peak to the greater shore. She could surely cross it, if no more horrors emerged from the sea to attack her — but then if they did, perhaps she could kill them too. She knew that she would continue to live in the Night Land and if she could, she would make it back home.

No. She could not turn back to the Great Redoubt. The sea barred her way to the South as surely as the crash did past from present. Her only route was North, towards where she had supposed the Lesser Redoubt had been built. She would go on, continue her journey.

The decision made, or made for her, she began to consider her needs item by item. To live and travel, she would need more than her insulated flight suit and a lightweight diskos; she would need food and armour as well. She went back to the cockpit and located the emergency packs of nutrition tablets and the powder that foamed to distil pure water from the air. On impulse, she wrenched a tooth from the tongue of the dead serpent and pocketed it as a trophy. Then she began to methodically strip the stained armour from Sartor’s body and rifle his flight suit for any more aids to her survival.

She stopped when the body was wholly exposed to her. Certain intrinsic things were revealed that were now irrelevant in death. She paused for while, amused at the mysteries that were resolved and the realisation of her own naïveté. “Oh why didn’t you tell me?” she cried aloud. Sartor did not answer, seeming instead to grin at this last joke. She continued in her task and ignored her tears.

She put the armour on herself, discovering that the range of adjustment was enough to accommodate her own frame. She was careful to tighten every strap and spring and elastic cord and to check that its power cells were fully connected so that the complicated device was worn like her own skin. From now on it would be her own skin: the armour was her face to the Night Land and all that separated her from death. This butterfly would undergo another metamorphosis inside the shell on her long walk to her destination, or she would not make it at all. She would keep this armour forever and indeed she would become a hero, exactly like Sartor. Her fame would buy her a new life, or she would be Sartor’s phantom: she would pretend to be Sartor, which would be easy enough. Yes, she would be the living Sartor in her own heart. She repeated the name over and over to make sure that it fitted.

She turned back to where the body of her love lay. She could bury it, but a scavenger would dig it up. No matter what she did, it would decay and be consumed and defiled. The Sartor that she had known would have wanted most of all to remain at the controls of the machine, so she left it there, its bare hands and face exposed to the air and those deep black eyes open to the darkness. She kissed Sartor one last time on the lips, fixed her mask over her face, took her new name and diskos with her and walked away down the hill, across the causeway and towards the Lesser Redoubt.

© 2003 by Brett Davidson.

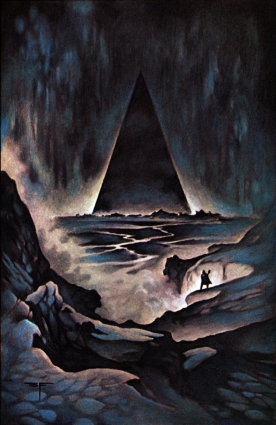

Image copyright by Stephen Fabian.