A Mouse in the Walls of the Lesser Redoubt (Part 6)

by

Nigel Atkinson

To A Mouse in the Walls of the Lesser Redoubt (Part 5)

“We are ready to begin, My Lord,” Aldous said.

The Master nodded and Aldous called his team of operators together. The redheaded, freckle-faced boy was small for his age, but the Master could easily see him heading a revived Electromechanics Guild. He settled back in his chair, and watched as the instrument was assembled around Naani. He had decided in the earliest days of the work that the children would use the Master Word machine. It was their great achievement, and they deserved the chance.

In any case, he doubted he had the skills and strength needed.

The children decided among themselves who would be first. There was no discussion, and no campaigning. A secret ballot was held and, apart from her own vote for Aldous, Naani was the unanimous choice.

The Master watched while final adjustments were made. The urge to intervene was almost irresistible, and he found himself missing Bergthora’s quiet calm. Unfortunately, she was somewhere in the Redoubt, searching for the fifty-ninth child — her ever-elusive son.

“With your permission, My Lord,” Aldous said. “Naani is ready.”

Naani smiled at her father. She was standing on a glass plate and was surrounded by a horseshoe of stacked white cylinders, each a foot in length and three inches around. The cylinders seemed to be hovering in mid-air, but that was an illusion. They were encased a framework of glass so transparent it was hard to distinguish from empty air. The reason why such an exotic, fiendishly difficult to fabricate, material was needed was a mystery. The children joked that it was just for decoration. The Master secretly rather liked that idea; if after millions of years of silence, they discovered they were not alone of the Earth, the instrument would have earned its rich garment.

“Hello,” Naani said quietly.

The solemn throb of the Master-Word beat out into the Night. Many of the children fell to their knees, gasping; for the Master it was like being truly alive for first time.

“A voice!” Naani shouted. “I am answered!”

“Call again!” Her friends cried through their tears.

Mirdath — Mirdath — Mirdath!

Naani shook her head in disbelief. The instrument fell silent, and the endless river that carried the Master-Word faded away. The children clustered around Naani, bombarding her with questions. They parted as the Master stepped forward and touched his daughter’s hand.

“Are you well, my child?” he asked.

Naani smiled broadly. “I have never felt better in my life.”

The children’s questions persisted: “Who is Mirdath? It felt like you knew this woman — it is a woman, isn’t it?”

“Yes,” Naani said quietly. “I think she is a woman. But I don’t know who she is, I think I must have remembered her name from an old book I read once. I’m not sure but I think it was a love story.”

She looked wistfully at her father, and he caught her mood.

“It is best if Naani rests now,” he said. “She can try again later. What you have achieved here is remarkable, and epoch-making, but it is best to take things slowly.”

The children agreed reluctantly, and began disassembling the apparatus. The Master reached out and touched their thoughts; the warm thrill of the Master-Word still beat in their minds. Almost as much as Naani’s success, that simple resonance heartened and dismayed him. The children were different — the Master-Word of the Great Redoubt had quickly faded from his thoughts and, after only five minutes, he could hardly recall its shape or sense.

The tavern’s doors were closed and locked, but a group of drinkers still clustered around a table in a dimly lit back room. Their flagons of moss beer were full, and the air was thick with the smoke from their bacca pipes. A man whose muscular farmer’s build was in marked contrast to his withered right arm, leaned forward and started hard at Caliban.

“Do that thing again,” he said in a voice slurred by too much drink.

The boy stared back at him and smiled thinly. Farmer folk were notoriously clannish and distrustful of outsiders but, despite being outnumbered six to one, he didn’t seem to be intimidated.

“Why don’t you try it?” Caliban said calmly.

The farmer swept his good arm across the table, sending several flagons crashing to the floor.

“Don’t mock me, boy. I want proof before I’ll sign up for this.”

Caliban smiled again, and nodded almost imperceptibly. He held his hand palm-up and fingers spread for a few seconds, then inverted it and pressed down on the table. The watchers crowded close. Caliban noticed that his loud-mouthed friend wasn’t looking at his hand but his face. He wasn’t worried, after a lot of practice he found he could bear the agony without it showing in his expression. The pain was dreadful beyond words, like burning rivulets of acid coursing through his flesh, but he had no intention of letting these peasants see his suffering. He was in control here.

He smiled and looked down. His fingers were buried three inches into the oak table.

“Who are you?” the farmer asked.

“You can call me Harlequin,” Caliban said.

“Mother! Will you stand still long enough to listen to me?” Theodora demanded.

Bergthora looked up briefly then continued loading Hour-Slips and bound books into the arms of the young apprentice. The girl was having trouble balancing her load, which almost reached to her chin. Theodora found room for a last Hour-Slip under her arm then shooed her away. The poor girl tottered out of the hallway, but a few moments after she passed from sight there was a subdued crash from outside.

“Jessamy, are you all right?” Theodora shouted.

“Yes, My Lady,” came the muffled reply.

Bergthora sat down on a white-painted wooden stool. “Well?”

“Well? What do you mean well? I’m your daughter!”

Bergthora smoothed away a crease on her dress. “Yes, you are. And I will thank you to show the dignity and politeness you were taught.”

Speechless with exasperation, Theodora paced in front of her mother, who waited patiently. The sounds of running feet and excited young voices filtered in from outside.

“You must use your influence, Mother,” Theodora said eventually. “Things are going from bad to worse—”

“The Master is well-aware—”

Theodora knelt down pressed her hands into her mother’s. “My Guild is dying,” she said. “The Jackotrades have almost deserted us.”

“Many old certainties are being challenged.”

“You should see Master Hugh. It’s terrible what this is doing to him. When it first happened he took to drink. But—”

“There was trouble?”

Theodora shook her head. “I won’t say. It was a mistake and everyone involved forgives him. But since then he has been like a walking dead man. I almost wish he would take a drink again, but he swore an oath never to again.”

Bergthora touched the tears flowing down her daughter’s cheeks, and spoke softly. “I am so sorry.” She helped her daughter to her feet. “Be brave, my sweetest and only child—”

Her words jarred Theodora. “So I have no brother now?”

“You never did,” Bergthora sighed. “It is best you never think of him again.”

“I hardly ever do. It’s like the time when I was sister to an innocent baby, who turned into a happy little boy, happened to someone else. What went wrong? I know it was about the time he was Assessed—”

Bergthora ignored her probings. “I don’t know. Just fate I suppose. We were not to blame. No one was.”

There was a soft knocking from outside and the apprentice girl came in again. She glanced in surprise at Theodora, then curtsied to Bergthora.

“Begging pardon, My Lady, but you are needed in the—”

“Yes. I will be along very soon. You are dismissed.”

The girl scurried from the room as if a Sand Viper was chasing her.

“She is one of your special children?” Theodora asked with raised eyebrows.

“Jessamy is perhaps not the brightest jewel, but she works hard. Maybe that is enough in these dark days.”

“Master Hugh worked hard,” Theodora said bitterly. “Is his fate in the hands of such as her?”

Her mother just looked at her. She did not try to speak mind-to-mind nor did she change her neutral expression.

“Tell me there is hope,” Theodora said slowly.

Her mother’s silence was more expressive than a thousand words.

“How many times has she tried since her first success?” Bergthora asked quietly, still mulling over the difficult meeting with her daughter the day before.

The Master scowled. “Six times, and all of the other children have tried — and failed.”

“Maybe conditions are wrong . . . somehow.”

“Somehow? And if they were what could we do to change them? It has been millions of years since humans attempted a task so complex. The truth is that we are like worker bees. Blindly we built our hive, but we have no idea what it does, or how it works. The machine is beyond our comprehension. We were just lucky the first time — or deluded.”

“We can try again tomorrow. Or maybe you should try—”

“I cannot. If this thing is to be done it must be done by the children. That much is certain.”

The Jackotrade colony slid through the interstices of the metal wall, and pooled together on the floor. Attracted by the soft hum of the Earth-Current, and the subtle, metallic tinkling of the Master-Word, it flowed toward the glass and metal mountain standing in the centre of the room. The colony touched the glass cliff and exchanged ambassadors with the tribes inhabiting the instrument.

The metal floor was chilly under Naani’s bare feet, and the only light came from the machine. The other children were all asleep. The Prefect guards were awake, of course, and had watched quietly as she left the dormitory. One of them had fallen in behind her, but remained outside the room. Unsure of why she was drawn here, she walked slowly around the partly disassembled Master-Word machine. Then she sat down inside the instrument. It hummed softly and was slightly warm to her touch. She closed her eyes, and let her mind fill with thoughts about Mirdath and her bright warrior. Theirs was an ancient story, a tale of love and loss, filled with strange conceptions such as the mystery of the evening, the glamour of night, and the joy of dawn. Feeling guilty, and oddly childish, she allowed herself to imagine that bright warrior of her dreams was the ancient hero, somehow brought back by her love.

The Master-Word enveloped her softly, and suddenly she felt light-headed. This wasn’t the strident, bell-like chiming of her first experience. It was more delicate, yet somehow deeper and more textured. There was no reply, but she sensed that someone was listening. Laughing quietly with joy, she let her thoughts of love and life tumble into the aether.

Behind the instrument, the Jackotrade colony made its chemical and electrical farewells, then slipped through the floor.

Engineers swarmed over the Earth-Current machine, desperately trying to trace the source of the problem. They clamped instruments to the torus and the conduits that snaked away from the twelve turbines. But the changes in the machine’s music continued. Dissonant overtones calved from its normal pure note, and there was an almost subliminal grating noise coming from somewhere under the machine. In control rooms set into the walls, supervisors stared in disbelief and fear at the growing fluctuations in the current. They could find nothing wrong with their engine — the fault seemed to lie with the Earth. It was almost as if the orientation and spin of planet’s magnetic core were fluctuating, setting up dangerous sympathetic vibrations in the generator. Needles flicked off-scale, and numerals blurred, and the dissonance turned into a shrieking whine that penetrated every cell of every person’s body.

The Masters of the Guild conferred. Their discussion was brief — it was obvious that they had no alternative — unless something was done, the Earth-Current generator was going to shake itself to pieces.

The eight highest-ranked among them stood at their appointed stations, inserted their sigils into ten small apertures and, when the word was given, turned the Earth Current machine off.

The Gallowglass stared at the empty, bitter, tannic dregs in his wine cup. His stomach was sour, but not from the wine. He had spent a sleepless night pacing the Prefecture halls, endlessly mulling over the Master’s bizarre revelations. Now, he sat alone in the Buttery, unable to decide what was worse: the grotesque idea that the Redoubt must be sacrificed to save humanity or the Master’s growing fatalism. For decades he had defended the Lord of the Redoubt by word and deed. Now, for the first time he began to see the Master as the people saw him, indecisive and capricious; one moment too fearful to act, the next forcing the pace of change too hard.

It was a sobering vision, and he knew it was unfair. The Master didn’t cause the Jackotrades to desert, or fill the Legions of the Night with bitter hatred for humanity. Nor could he be blamed for his fractious people — the Gallowglass blamed himself for that — he should have stamped on the first signs of trouble decades ago. But despite all the great questions facing the Redoubt, he suspected that the Master’s biggest problem was his lack of self-belief. Many times over the years he had dropped sour hints about his election. Two decades since he put on the ruby robes, he was still half a century younger than the next youngest Master in history was at his election. It was obvious that the Monstruwacan Council had elected him precisely because they expected to be able to easily manipulate such an inexperienced man.

They were wrong. For good or ill, whatever really happened during his enKernelling, it had put the Master beyond the reach of mere political machinations.

At that moment the Earth Current failed.

The Gallowglass took an instant to orient himself in the pitch darkness, then strode quickly out of the room, easily avoiding the chairs and tables between him and the door. Outside, a squad of Prefects ran towards him, their spinning Diskoi lighting the corridor. He snapped orders at them. "Wake the Prefecture! — assemble everyone on the Parade Ground! — find lights!"

Fire broke out in a draper’s shop in the Shambles district when a hastily improvised oil lamp fell over. The burning oil splashed onto curtains and boles of cotton, and set them alight. In a few minutes the shop was ablaze and burning debris was drifting down the street. People reacted well, waking their neighbours and organising bucket chains to get water to the seat of the fire. At first they appeared to be gaining ground on the fire. Then the water supply slowed to a trickle. Cursing their luck — and the Redoubt’s government — they fell back to safe ground, and watched the fire destroy their homes.

The Redoubt’s ventilation system was convoluted, and linked the entire edifice together in a contiguous system. The smoke billowing from the Shambles was sucked into massive ducts and quickly spread to unaffected areas. Thousands of people woke up choking in the dark, terrified for themselves and their families. Those who stumbled from their homes walked into a living nightmare. Desperate mobs formed, attacking anyone who was foolish enough to show a light.

The Moramor led a platoon of Prefects in a fast run around the circumference of the Great Arbour. Apart from the light from their Diskoi, the only other illumination came from a few windows in the Guild Houses they passed. His orders were clear — defend the children — at all costs. Six Prefects already guarded them, but he doubted that would be enough. The squad ran in silence, a little moving island of light in the immense darkness. Suddenly, there was a trace of smoke on the air and, in the distance, another group of flickering lights was racing across the Arbour. The Moramor squinted, but it was too far away from him to see, he needed younger eyes.

“Sergeant, how many men in that crowd?”

“At least two hundred, My Lord.”

“Faster!”

The Prefects reached the children’s Guild House while the mob were still three hundred yards away. Calmly, the Moramor ordered his men into a skirmish line in front of the house, and waited for the mob to arrive. They were mostly men, although there were a few women in their ranks. They carried flaming, pitch-soaked torches, and hastily improvised clubs and quarterstaffs. Over their heads crude banners flew. Some were red with a white hand whose fingers had been cut off at the knuckles, others were a riot of coloured patches like a jester’s motley.

The Moramor stepped forward.

“Stop, place your weapons on the floor, and walk slowly away from this place,” he said in a voice that carried easily to every person in front of him.

The crowd halted for an instant, then a burly man with a withered arm walked forward. His good hand held a hefty wooden club. He stood a pace away from the Moramor. “There are only a dozen of you. We are hundreds strong. Let us through, we have business here.”

In a blur of electricity the man’s head spun away from his body. Before the corpse hit the floor, the Moramor was in his place in the picket line.

“Prefects avaunt,” he ordered.

A ripple of chained lightning swept along the thin line of Prefects as they brought their Diskoi to battle-ready. The men at the front of mob quailed for an instant, then were pushed forward by the growing press behind.

Bergthora slipped into her old habits of secrecy and disguise, and had been able to blend into the crowds milling in every open space. The Earth-Current had been restored six hours ago, ending the half-day-long nightmare, but there was still widespread anarchy. Everywhere she went she heard angry demands for retribution — the higher-ups had failed them, and the people demanded scapegoats. Anyone who looked like a noble was in danger of being set upon but, in her farmer’s smock and old boots, she was able to pass safely. Trying not to look like a woman with a purpose, she flitted from place to place, stopping regularly to listen to ranting orators, even adding her own cheers when it seemed sensible to. The speakers railed about scandalous failure of the Redoubt’s government, especially the Master Monstruwacan. They wanted the old ways torn apart, but seemed to have little to offer in exchange. Some spoke of an enigmatic man who could walk through walls and had chained the energies of the Night to him. Improvised banners with truncated hands painted in bright red waved, and their owners cheered wildly.

Gradually she closed the distance to the children’s house. The other Guild Houses were shut up tight, and most of them had Prefects watching warily from roofs or high windows.

Some were less lucky: the Ancestors’ House had been burned to the ground, leaving only cinders and ash to mark the passing of one of the Redoubt’s oldest Guilds.

A crowd of hundreds of people surrounded the children’s house. Bergthora pushed through them, treading on feet and using her elbows without compunction. A couple of fights broke out in her wake, but she kept going. Strangely, the crowd thinned a little at the front, and the going was suddenly easy. The people were quieter too. It was easy to see why; one look at the carnage in front of the house was enough to silence anyone. Sliced up and burned bodies were piled like a rampart. Most of them were rioters, but she could see the remains of several Prefects among the grisly pile. At first glance the house seemed undamaged, then she noticed the smashed-in doors and broken windows. Setting caution aside, she opened her mind. For a time all she could sense was hatred and fear — mostly fear — so she battled to filter the gross emotions out and tune her mind to search for the children.

The house was empty. If any of the children were inside, they were surely dead. She nearly abandoned herself to grief, and then she noticed a dirty knotted handkerchief hanging from a broken window. Carrying a faint hope in her heart, she made her way slowly back through the crowd.

The tunnel was long, hot and foul smelling, and slimy water dripped from the roof. The Moramor’s right arm ached and his tunic was stiff with crusted half-dried blood. When the mob had surged forward, someone had stuck him with a crude spear. An upward slash of his Diskos had disposed of his attacker, but had been left with the broken-off tip of the spear grating against his collarbone. They had been running through the old tunnels for at least two hours, and the children were in desperate need of rest, but he was still afraid of pursuit. His men would have hidden the secret way out, and defended it with their lives, but there was always the chance of discovery.

He had failed once today. He had no intention of failing again.

Someone pulled at his elbow, triggering off a volley of stabbing pains in his shoulder.

“Moramor, we must stop, we need water and rest.”

“I’m sorry, Lady Naani, we must keep going on.”

She stepped in front of him. “No. We must stop now. We can’t go on without water. People are becoming dehydrated.”

He saw the exhaustion in her eyes, and the cracks around her lips, and realised she was right. He took off his jerkin and handed it to a boy standing beside Naani. “Knot a sleeve and the wrist, then pour water through it. That will filter any badness out.”

Naani watched the boy collecting water in the jerkin. After a few seconds clear droplets began to trickle from its tapered bottom. Cups appeared out of satchels and were used to collect the pure water.

“That is a clever thing,” Naani said. “The fabled resourcefulness of the Prefects—”

“Do you mock me child? I left good men to die to save your lives.”

Naani put a hand to the Moramor’s face. “You are hurt.”

“It is nothing. Gather the water, then we must move on.”

“Arian, come here. The Moramor is injured.”

A tall, fair-haired girl joined Naani. She brushed aside the Moramor’s complaints and ordered him to sit down while she examined him. Surprisingly, he obeyed. Arian opened his jerkin and carefully examined the wound, using both eyes and mind. Then she tore a long strip of cloth from her own dress and used it to pack the wound. The Moramor flinched as she tightened his clothes.

“This is a serious injury,” she said. “Something is buried inside his shoulder, and I cannot risk cutting it out here. It is close to an artery and the bleeding might prove fatal.”

“How far do we have to go?” Naani asked.

“Another two hours, maybe,” the Moramor replied. “Then we should reach one of our hidden forts. There are supplies there, and security. We will have time to plan our next move.”

“Good,” Naani said. “When everyone had had water, we will move again.”

Just before they set off again, Aldous came up to Naani and the Moramor. He held up an index finger. A sliver of quicksilver was curling around it. “Jackotrades,” he said. “The walls are saturated with them.”

It was late in the day when Bergthora reached the Vault of Ages. Most people had returned to their homes or, if they had no homes to go to, congregated in impromptu camps in the Great Arbour. With the Prefects out of sight and the Guild Houses buttoned up tight, there were no clear targets available. Violence still simmered close to the surface, but the mood seemed to have calmed down a little. She could also sense widespread shock and shame at what had happened when the lights went out.

She took a roundabout path to the Vault of Ages, avoiding the main entrance, guessing that would have been a likely target for rioters. She opened a secret door in the rarely visited Western side of the Vault. A terrified-looking Prefect apprentice immediately challenged her. His only weapon was a short sword, held in a trembling hand.

“Look at me,” Bergthora said. “Do you recognise me?”

“I think so.”

“I am Lady Bergthora Baumgard, have you heard of me?”

Recognition dawned on the boy’s face. Bergthora sensed that he was desperate for anyone familiar. “Yes. I mean yes, My Lady.”

“Good.” Bergthora spoke quietly and slowly, careful not to frighten the boy. “You have done well, Prefect Apprentice. The Gallowglass will be proud of you.”

“You know of the Gallowglass? What news have you of my brothers? I was ordered to guard here when the Earth-Current failed.”

“Hush, hush,” Bergthora said. “Things are difficult outside. It is hard to get accurate information.”

“Then I must return to the Prefecture.”

“No! Not yet,“ Bergthora said quickly. ”Do you have food and water?”

“I have field rations for a week.”

“Then stay here for a few days. Follow your orders. When you leave remove your uniform and avoid other people.”

Realisation dawned on the boy’s face. “How bad are things?”

“Bad enough that you getting killed won’t change anything. Promise me you’ll stay here.”

“I promise, My Lady.”

“Good. I must go now, I have business in the Vault.”

The young Prefect nodded. Bergthora could only hope that his old habits of discipline and obedience would keep him safe in his bolt-hole for as long as possible — she feared he would have little chance outside.

The Search Engine rocked from side-to-side, and a thin trickle of smoke escaped from a crack in its casing. Bergthora could hear the faint whining of its internal mechanisms, but it was clear that the machine was dying. Compared to the carnage happening all over the Redoubt, wasting pity on a machine seemed absurd. Nevertheless, her heart ached for it.

“I’ve smashed them all.”

Bergthora spun around, her heart racing. The Master was leaning against a pillar. He was holding a long metal bar. It was bent and battered.

“They will not deceive anyone again,” the Master said. He held up the bar, and looked at it strangely, as if seeing it for the first time. He shrugged and let it slip through his fingers. It landed with a dull metallic crack.

“My Lord—”

“I am nothing. Don’t call me that.”

Bergthora stepped forward and slapped him across the face.

He smiled, and touched the red patch on his cheek. “You have wanted to do that for a long time.”

She slapped him on the other cheek. “Pull yourself together! The Redoubt needs you now more than ever — your people need you — the children need you!”

He flinched as if she had slapped him again. “The children’s house was ransacked,” he said bitterly. “They are all dead.”

“Some survived — a secret sign was left on their house — there is hope.”

“There is hope,” he repeated, then fell to his knees. “I thought the last chance had gone. I though it was too late for my bargain . . . that it was too later for Naani.” Tears filled his eyes. “There is hope? I didn’t know. I think it’s too late now. What time is it?”

Bergthora recoiled from him, realising that something was terribly wrong.

“What have you done?”

“Do you really want to know?”

“Tell me everything.”

He smiled thinly and told her about the forgotten experiment he found hidden in the rock above the Great Arbour: how it too him years to discover the machine’s function, and how crushed he was when he realised that it was just another failure. But he never forgot about the hidden room, and when his people fell into anarchy he remembered, and conceived of a use for its mechanisms.

The experiment was a desperate throw of the dice by a people assailed by the forces of the Night, and searching for any hope. The idea was that the immense pressures that existed between the palladium atoms in the cube could be used to crush hydrogen and deuterium atoms together, liberating vast amounts of energy in the process. The experiment had been doomed to fail; even its creators eventually realising that their early results were phantoms. More seriously, the small-scale prototypes they created had a tendency to explode — killing several people in the process. Had they gone ahead with the full-scale test, the newly-build Redoubt might have been seriously damaged.

Just in time less radical pioneers were able to harness the Earth Current, relegating more exotic approaches to history.

At the last he had to be very careful. It wouldn’t have done for a spark of static electricity to start the destruction prematurely. He wore clothes and shoes made of thick cotton, and wrapped gauze around his fingers. He explained that he found the absence of choice comforting. It was like being a Search Engine with a set of instructions to follow — turn that dial, connect this pipe, bring the pressure of hydrogen up to that value. It took a surprisingly short time, then he flicked a switch that began the countdown to the destruction of everything he was sworn to preserve.

The palladium cube saturated with oxygen and hydrogen at the expected rate. After a few days the process would be irreversible.

“You see, I kept my part of the bargain,” he said. “The rest is up to the forces of the Night. The damage will be considerable, but nothing we can’t repair if we work together again like the Redoubt Builders did. Think of it as a new beginning.”

Bergthora knelt down beside him. There didn’t seem to be anything worth saying. Then she heard a distant rumbling.

For four days, bone-dry hydrogen and oxygen had trickled through the palladium cube. In the normal way of things, the equilibrium saturation of metal with hydrogen would be relatively low, significantly reducing the explosive yield. However, other forces had been at work. Every crack, crystalline flaw and atomic interstice was saturated with the gases. After four days pumping the critical point had passed. If a spontaneous reaction started inside the cube now it would make little difference to the outcome. The extra day passed, a circuit closed, and electricity began to flow through the cube. The potent cocktail of gases and metal had been teetering on the edge for days — the first few billion electrons were enough to push it over.

Oxygen and hydrogen fell together — and were blasted apart a picosecond later — the palladium cube exploded in a billion places at once — the shock waves met, crashed off each other and imploded — the second wave of explosions happened six nanoseconds after the first — releasing more than mere chemical fury.

Taking the path of least resistance, the explosion barrelled up the shaft and ripped the granite cap from its mountings. Ten tons of rock smashed into the roof fifty feet above and was blasted into dust and flinders. The flaming wavefront snatched the debris up and added their mass to its fury. Adjoining rooms were flattened; their wooden doors and brick walls swept aside like tissue. Two Prefects were the first to die: crushed as the empty corridors surrounding the ancient research centre imploded. An instant later, the walls of the shaft were punched back a dozen feet, vaporised ceramics melding with pulverised sandstone. The concussion sent cracks racing outwards through the bedrock.

The research centre was directly under the half-mile diameter collar of moulded basalt at the base of the ten-mile long shaft that linked the metal pyramid and the underground regions. Seconds after the first explosion, dust heaved from the mouths of the twelve tunnels leading away from the core. Concussions swept up the shaft. Carefully balanced beams and arms twisted then teetered past the point of no return. Flung by enormous, uncontrolled energies, the machines tore the shaft and everything in it to pieces. One by one, airlocks crumpled until there was nothing to hold back the ten-mile column of air above. In macabre symmetry, a katabatic avalanche of air killed at the foot of the shaft, while a sudden vacuum wrought similar havoc ten miles above.

The dying spasm of the Stress Masters' machines ripped the lining from the bottom three miles of the shaft, and the debris sealed the breach.

Two hundred feet of bedrock separated the explosion from the roof of the Great Arbour. The explosion’s energy propagated through the soft rock at ten times the speed of sound in air, recoiled from the surrounding granite intrusions, and crashed back to its origin. Concentric cracks propagated through the brutalised rock. Cracks bled into fissures, and fissures into fractures.

Monstruwacan Lindos was walking slowly under the Flying Wood. He was using a cane, still not having fully recovered from the incident in the Baker’s shop. He tried to ignore the pair of Prefects who dogged his every step. It had taken two hours of closely reasoned arguments before they agreed to escort him to back to his Guild House. Or maybe, he conceded, he simply wore them down. So far, the trip had been uneventful.

Then the world shuddered.

Millions of red oak leaves fluttered down as the fold in the Air Plug was overwhelmed. People began to panic as clods of soil and torn branches fell among them. Lindos was pushed over by someone he didn’t see; another person trod on his hand. Groggily, he tried to stand but was knocked down by a knee in his face.

A deafening howl of tortured rock silenced the screams.

Lindos lay on his back, his head spinning and his vision blurred. He couldn’t fully comprehend what he was seeing but the last rational part of his mind tried to calculate the energy that would be released when the Flying Wood impacted with the floor of the Great Arbour.

He didn’t quite have enough time.

The Arbourists, clustered in their control rooms halfway up the walls, had the best view. They watched cracks race across the roof and the twisting of the glass ropes that held the forest up. The ropes twisted and stretched then disintegrated into molten shards. The forest held together as it fell the half-mile to the Arbour floor — a tribute to the engineering skills of the Arbourists — many of who chose to leap to their deaths as their creation fell past them. After a surreal, silent fall, the wood landed with a soft flop, then disintegrated. A wall of soil and whirling branches swept outwards, crushing hundreds people who were far enough away to survive the initial impact.

Ears bleeding and heads ringing, the surviving Arbourists looked dumbly at the devastation below. A billowing, suffocating, cloud of dust was climbing rapidly towards them. The winding stairways to their control rooms had all been ripped from their anchors — and there was no other way out.

Then the roof fell in.

The Earth Current generator was seated on granite footings cut a half-mile into the crust. Its builders had calculated that only an external event capable of annihilating the metal pyramid would disturb its foundations. They were right, but they had not anticipated a self-inflicted disaster, tearing the Redoubt apart from inside. When ten million tons of rock crashed down three miles above, the generator room rang like cracked bell. Stairways and gantries rippled and tore apart; walls exploded into dust and, fatally, the generator’s footings shifted. Turbine coils glowed as they battled with the electromagnetic forces pulling them in every direction. A few turbines slagged into grey lumps, but most exploded, blasting rainstorms of white-hot metal in all directions.

Most of the thousand turbine workers were crushed or incinerated in the first seconds. The few who survived lived long enough to witness a possibility only hinted at in the most secret, most pessimistic annals of their Guild. Inside the Earth Current generator, the perfect, whirling circle of metallic hydrogen tilted by a tenth of a degree. Roaring with energy, the circle slipped passed its failing magnetic shackles and touched the metal walls. The detonation ripped out in a flat plane, annihilating everything it touched, splashing against the walls and burning its way deep into the rock.

As an encore, the air in the chamber exploded.

A last pulse of energy exploded thousands of lights, and then darkness fell forever in the Lesser Redoubt.

In the Vault of Ages, the Master Monstruwacan lay on the floor beside Bergthora’s body. The shattered ceiling tile that had killed her had missed him by a few inches, but he didn’t seem to have noticed. He kept saying a single word, over and over again.

“Impossible.”

To A Mouse in the Walls of the Lesser Redoubt (Part 7)

© 2002 by Nigel Atkinson.

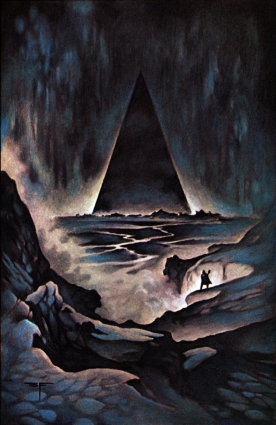

Image copyright by Stephen Fabian.