A Mouse in the Walls of the Lesser Redoubt (Part 4)

by

Nigel Atkinson

To A Mouse in the Walls of the Lesser Redoubt (Part 3)

The Master Monstruwacan knelt outside his daughter’s bedroom, his head pressed against the door. Naani was tossing and turning relentlessly, but his mind was attuned to deeper currents. Since turning fourteen, Naani had showed signs that she was growing strong in the Master-Word. It wasn’t uncommon for puberty to be accompanied by a sudden increase in mental abilities, but her new gifts were spasmodic and uncontrolled, and were strongest when she was asleep.

He opened his mind and was swept up in her dream.

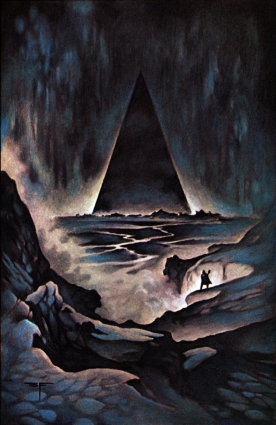

Naani walked through the ruins of the Lesser Redoubt, taking care to avoid the bodies of men and beasts. They were so closely entangled it was impossible to tell where one race began and the other ended. Effortlessly, she made the long climb to the apex of the pyramid and, when she reached the top, she stepped into sky. Buoyed by fleeing souls, she was wafted across an ancient sea. The ire of the Fixed Giants reverberated from the Shine, but she dismissed them with a glance, and headed Southwest. She skimmed the Great Gorge with its dark flanking forests, then plunged down an immense slope into a pool of darkness. She could see everything — and everything could see her. The luminous ring crowning the Northeast Watcher pulsed with every shades of blue, and its country-sized forehead crinkled extravagantly. The Silent Ones were wreathed in vagueness but watched her with keen interest.

Naani ignored all of them and swept towards the eight-mile metal high pyramid that dominated the surrounding works of darkness.

Beloved, where are you?

It is not yet time, my love.

When?

Be patient — fate will bring us together when the time is ripe.

Naani woke up for a moment, turned over and mumbled something unintelligible, then fell into a dreamless sleep.

The Master backed away from the door. He was soaked in sweat and his hands trembled, but he was ecstatic.

”My Lady! Where have you been?”

“We were worried—”

”You know your father doesn’t like you wandering off—”

“Especially these days, did you hear that the one of the Long Galleries had collapsed, My Lady?”

“Terrible it was, terrible—”

“Dozens were hurt—”

Naani’s maids surrounded her like bees around a honey jar. Their faces were red as acorns and they were breathless. That didn’t stop them chattering incessantly. In all her fourteen years, Naani had never been saddled with three such fusspots.

“I wasn’t anywhere near the Long Galleries,” Naani said. “I was just talking with that young gentleman over there, oh where’s he gone? Did you see him? He was quite handsome.”

The maids gagged for a moment, then after a brief, whispered conference, Melina — Naani was fairly sure it was Melina — adopted her sternest expression.

“That will not do, My Lady. Your father was most explicit that you are to be chaperoned when out in society. Running off and gadding about with young gentlemen is . . . unacceptable. What do you know about him? Is he well bred? Are his prospects bright? Mmm?”

The other two maids chimed in with mmm’s of their own, while fussing at Naani’s dress and hair. Naani was tempted to ask Moll (or was it Mimii?) if the underfootman she was so friendly with after curfew had good prospects.

“I didn’t ask the gentleman about his prospects, or his breeding. I think both were quite evident,” she said.

That set off another chorus of twittering. As her maids guided her back to the official reception, she wondered again about the young man. There was something familiar about him, but she couldn’t recall if they had met. He was about her age, and was charming, but evasive when she asked about his background.

All in all, he was quite the enigma.

Her maids chivvied her back to the dull party, and she smiled automatically as they introduced her to a succession of dull young men.

“More jam, dear?” Essa asked.

“No thanks, ma. I’m full up,” Theodora replied. “I’ve never tasted better scones than yours, but one can have too much of a good thing.”

“I’ll wrap some up for you to take to work,” Essa said, with a determined nod. “You’re working so hard these days, you must be sure to eat properly.”

“I’m working hard too,” Hugh mumbled.

“Did you say something, husband?”

“Never said a word,” Hugh said with a sly wink at Theodora.

“Good. Don’t you be letting him run roughshod over you, my dear. You’ve been his apprentice four years now, you probably know as much about those Jackotrades as he does.”

“I wouldn’t say that,” Theodora said, biting her lip to avoid giggling at the look on Hugh’s face. “Master Hugh is highly regarded within our Guild for his great experience—”

“Aye, he’s getting on,” Essa said with sad shake of her head. “No denying that.”

Hugh pushed his chair back. “I am going now. You two can cackle away to your heart’s content. Theodora — met me in a couple of hours at Guild House — we need to restock on savoury tinctures.”

“Yes, Master Hugh.”

Later, when they were doing the washing up, Theodora asked Essa a question that had been on her mind for a long time.

“Tell me, why didn’t you have children?”

Essa was up to her elbows in soapy water, and her apron was flecked with soapy bubbles. She smiled a small smile, and shrugged. “It wasn’t to be. We wanted a family, but like so many other folk these days, it just never happened.” She pulled a spotless tureen out of the sink and scrutinised it carefully, her face brightening. “I’ll tell you one thing, though.”

“What’s that, ma?”

“It wasn’t for the want of trying.”

Bergthora sat up in bed with her knees tucked under her chin. The bedroom was chilly, but that wasn’t why she was trembling. Beside her, the Lord of the Redoubt snored softly in a dreamless sleep. As his confessor, she could understand that; for sixteen years he had carried a terrible burden, and it must have been a tremendous relief to finally let another person share the secret.

But why me? Why do I have to know this thing? Am the only person in the world who he truly trusts?

For a guilty moment, she wished she could wind back the day to before their walk in the farmlands that fringed the South of the underground lands.

“You aren’t worried that people will see us?” Bergthora asked.

The Master Monstruwacan held her hand a little tighter and nodded towards the saffron groves. A dozen heads poked above the soil ramparts. “I think it is a little late to worry about that,” he said. The heads disappeared one-by-one as the Prefects flanking the Master and Bergthora’s path approached.

“Did you notice?” Bergthora asked. “The men and women work together.”

“The farmers have never bothered with such niceties as dividing life’s work up between the sexes. If a job needs doing someone does it.”

“A good example.”

“I did not ask you to accompany me so you tell me things I already know.”

“No, My Lord. I am sorry. You want my report on the children. There is an seat over there, shall we rest?”

“If you wish.”

The seat was rough-cut from a block of limestone and was sited on a little mound overlooking the nearby groves. The farm workers looked up as they passed by. With a sudden flash of insight, Bergthora realised that the Master wanted her to be seen with him. Scandalised rumours would spread through the Redoubt’s markets and taverns, and maybe deflect attention away from other things.

“The Children,” the Master said.

“Yes, My Lord. ” She took a tight-wound sheaf of Hour-Slips out of a fold in her bodice, and took out a single slip. “This month’s summary. One child was lost, the girl Chami, who died from the coughing fits.”

“At fourteen?”

“A thorough investigation was done. There is no reason to believe her death was anything but a natural tragedy.”

The Master shook his head and smiled thinly.

“The fifty-nine surviving children are all in good physical health—”

She stopped talking as two men hauling a handcart full to the brim with cabbages and parsnips passed by, filling the air with a rich loamy smell. One of the men smiled and waved. Bergthora overheard the Master’s mental command to the Prefects — let them pass in peace. She watched the cart roll away around a corner, and the Prefects fanning out to prevent a repeat of the interruption.

That they had allowed the men to get so close in the first place was surprising, and a little worrying. The Master shifted a little beside her, and she felt his impatience.

She consulted the Hour-Slips again. “On average, their mental and physical abilities are only a little more pronounced that the older and younger control cohorts. There are exceptions, of course. The boy Aldous shows tremendous intellectual promise, Arian has empathic gifts that suggest she will become a great healer . . . and your daughter appears strong in the Master-Word—”

“Such things are relative. None of us comes close to the strength of our ancestors.”

“Her potential is undeniable—”

“Continue your report. We will discuss individuals at another time.”

“Yes, My Lord. As might be expected, the parents of the boys are staring to make representations to their familial Guilds, and the Prefects have shown interest in three of them.”

“I will decide which Guilds the children will be apprenticed to — including the girls — and I will take steps to deflect the interest of the Prefecture.”

“Yes, My Lord. One other thing—”

“Your son,” the Master said through tight lips.

Bergthora stood up, suddenly angry. “Preserve us! Will you stop picking my mind? I have a right to privacy.”

The Master’s expression softened. “Do not be absurd. You concern for the boy is like a beacon; I have no need to step inside your head to see your worries.”

“The Prefects hunt him.”

“In the last week treacle was used to block the pipes of the Musician’s Guild’s Harmonium, a plague of cockroaches infested the Baker’s district, and offensive graffiti about the Prefects has appeared in several different places. Silly and pointless acts, but a growing source of friction and a drain on the Prefecture’s already stretched resources. This time if they find him, he will be flogged and put to hard labour for a year, and there is nothing even I can do to save him.”

“There is no proof these were his acts. Your regime is hardly popular, many people are opposed to your reforms.”

“The people of the Redoubt are not given to malicious acts of vandalism, your son is unique in that respect.”

“I wouldn’t count on that—” She stopped herself just in time from raising the unsolved murder of the Bee Master.

The Master shook his head angrily. “You try my patience, woman. The Prefects will catch they boy eventually, and quickly extract the truth.”

“No they won’t.”

“Pain is a great incentive.”

“I wouldn’t rely on that. I saw him put his hand in a flame once — I think he knew I was watching. He held his hand in the flame for minute after minute. I swear I could smell his flesh crisping. He showed no sign of pain, only amusement.”

The colour drained from the Master’s face. “Life’s breath — what if he is the one?”

Bergthora sat down, and took his hand in hers. “Maybe it is time you told me what happened when you were enKernelled?”

The Master was silent for a long time. “Yes, you are right. But not here. Let us return home.”

He told her everything over a meal of pomegranates in lavender jelly with caramelised grasshoppers. The sweetmeats were among her favourites but, as he told her of his bargain with the Fixed Giants of the Shine, she decided she would never eat them again. Such petty self-punishment was absurd, but she had to do something.

She lay awake for several hours, mulling the Master’s revelations over. She pushed aside a lock of hair that had fallen across his face and wondered if he was, in fact, quite mad.

Don’t be absurd. He is the sanest man in the world, how else could he have hidden this thing for so long? The questions I have to answer are all directed at me, not him — a fact he knows perfectly well.

She remembered staring at her half-eaten bowl of grasshoppers while he told her that everyone was going to die.

No, not everyone — there will be a survivor — could it be my son?

“I found a strange old tale in the Vault of Ages,” he said after a long silence.

“You spend to much time there,” she said automatically.

He ignored her. “In the Dawn Times, even before the Age of the Moving Cities, when humanity still had ambitions, they did a great and daring thing. Tens — hundreds — of thousands of people worked for decades to build a great machine, to launch a single man into the heavens on a pillar of fire.”

“Why?”

“To see what’s there, I suppose.”

“What did he find?”

“I don’t know.”

“That’s not much of a story — oh, I understand — you see it as a metaphor for the eight million years we have been bereft of the rest of humanity. That is a thin reason to take these great decisions.”

He picked at the skin of a pomegranate slice with a small fork. “I have other reasons. Are you with me?”

“Yes, My Lord,” Bergthora said a little too quickly, wondering what he would do if she had said ‘no’.

The Search Engines climbed over each other exchanging information in their mysterious language of cogs and ratchets, sprockets and pinions, hairsprings and worm drives. A dozen of them were rolling around together in front of the Master Monstruwacan, while thirty more were climbing the pillars of knowledge, looking for snippets of lore, or obscure connections.

He had stumbled on this new way of programming the Search Engines by accident. Twelve months ago, just after the murder of the Bee Master, he had found a hidden panel on one of the engines. Inside was a set of eight cog-toothed wheels. Intrigued by this new enigma, he thumbed the unmarked wheels up and down randomly. Nothing happened for several minutes, then something inside the machine clicked. The Engine rolled away from him and clambered over one of its companions. At first he assumed it was an accident, or maybe he had damaged the machine’s gyroscopes, but then he realised that the two engines were moving with a unified purpose.

It took him two months to discover that this was how information could be passed from one Search Engine to another, and another four to develop the programming techniques needed to take advantage of his discovery. For a time he hoped to revolutionise the gleaning of knowledge. A year on from his discovery he was less optimistic. The new technique seemed to prevent Search Engines from duplicating each other’s efforts, which was a useful breakthrough, but the higher levels of efficiency he suspected existed still eluded him.

Just like the answers he needed.

A tinkling of bells caught his attention. The clan of Search Engines had reached some sort of conclusion. In their arcane way they had chosen one of their number to approach him. He fancied that its wheels and gyroscopes were perhaps spinning a little smoother than the others. It had lived up to its potential. It wasn’t the machine’s fault that the answers it was ready to show him were almost certainly useless. Humans had created the machines, and humans had lost the secrets of how to use them effectively — assuming they had ever known. He wondered if, left to themselves for eight million years, they might have evolved into a higher form, capable of accessing and synthesising the lost learning into something useful, and maybe revelatory. He realised he was saddened for the mechanism. It would fail, and he would reset its whirling mechanisms, taking away the atom of consummation it had accrued.

The Search Engine was rocking slightly from side-to-side. In pity, not expectation, he leaned forward and tapped a little brass button that was labelled ‘execute’ in an ancient language. The irony of seeking knowledge by calling for its death was not lost on him.

The Search Engines began their oracular gavotte, swarming up pillars; the fleetest among them quickly disappearing into the gloom high above. He looked upwards, wondering what complexities lay hidden in the design of the Vault. Eight years ago he had discovered that a small number of pillars were special: their jackets of words and pictures were veneers hiding vacuous natures. They held no knowledge worth having. At first he had been angered at this wasteful deception. But later, while recording the gross characteristics of the Vault, he began to notice patterns. Four of the seemingly useless pillars would be set at the corners of a square a mile to a side. Sharing each corner was a circle of six more, and centred on that a two-mile diameter octagon. He realised that other patterns were waiting to be found. He even knew what to look for. The missing patterns would complete a sequence enumerating the faces of the five perfect solids: pyramid, cube, octahedron, dodecahedron, and icosahedron.

It had taken him two and a half years, but he eventually tracked the eight and twenty sided patterns down. The dodecagons orbited the numeric core with their centres fixed on vertices drawn through the centres of the square, circle and octagon. The twenty-sided figures were the most enigmatic. They grazed the outermost angles of the dodecagons, but were truncated by the rock walls of the vault.

The significance of their stunting escaped and worried him.

Naani turned the rose in her hand; it was perfectly symmetrical and had the most vivid red colour she had ever seen. She inhaled its sweet scent and glanced at the boy standing beside her. He was still an enigma. This was the second time in a week she had slipped her maids to keep a secret meeting with him. The Prefects would have been alerted by now and would be looking for her. It wouldn’t take them very long to find her, and she could expect a long scolding, and probably a slippering, when she was taken home. At that moment, she didn’t care.

“It’s beautiful,” she said, twirling the rose.

“I suppose so,” Caliban said.

“Where did you get it?”

“Read my mind.”

“You know I can’t.”

Caliban grinned, and leaned over the balustrade. They were on the fifteenth tier of the Arbourists’ galleries, level with the bottom of the Flying Wood and a quarter mile above the floor of the Great Arbour. Suddenly, Caliban spat over the edge.

“Oh, that’s disgusting!” Naani said.

Caliban pantomimed outrage. “Oh, golly! I’ve broken the law! Call the Prefects!”

“Well, it’s wrong and—”

“Disgusting?”

“Yes.”

Caliban nodded at the rose. “Funny, you don’t seem to mind breaking the law when it’s about something pretty. Oh, didn’t you know? Having stolen properly is against the law.” He wagged a finger. “Ignorance of the law is no excuse.”

“Where did you steal it?” Naani asked.

“From the Shrine of Anamnesis in the Garden of the Dead.”

Naani let the flower fall from her fingers. It tumbled into space and wafted slowly towards the Arbour floor. She stepped back; her hand left compulsively gripping the balustrade. “Get away from me! I never want to see you again.”

Caliban reached forward, grabbed her dress and pulled her close. “No, let’s wait. The Prefects will be here soon. They might even catch me. It’s not very likely — they aren’t too bright. But if they did, you could watch them flog me. Would you like that?”

Naani pushed hard and Caliban fell over and ripped a handful of silk out of her dress. She covered herself up as best she could and ran away. Caliban’s laughter followed her all the way to the door.

To A Mouse in the Walls of the Lesser Redoubt (Part 5)

© 2002 by Nigel Atkinson.

Image copyright by Stephen Fabian.